Phenomenology

Index

- Introduction to Phenomenology

- Philosophical Foundations: Edmund Husserl

- Phenomenology and Sociology: Alfred Schutz

- The Lifeworld and Intersubjectivity

- Typifications and Social Knowledge

- The Subjective Meaning of Action

- Phenomenology vs Positivism and Structuralism

- Applications in Sociological Research

- Critiques and Limitations of Phenomenology

- Conclusion

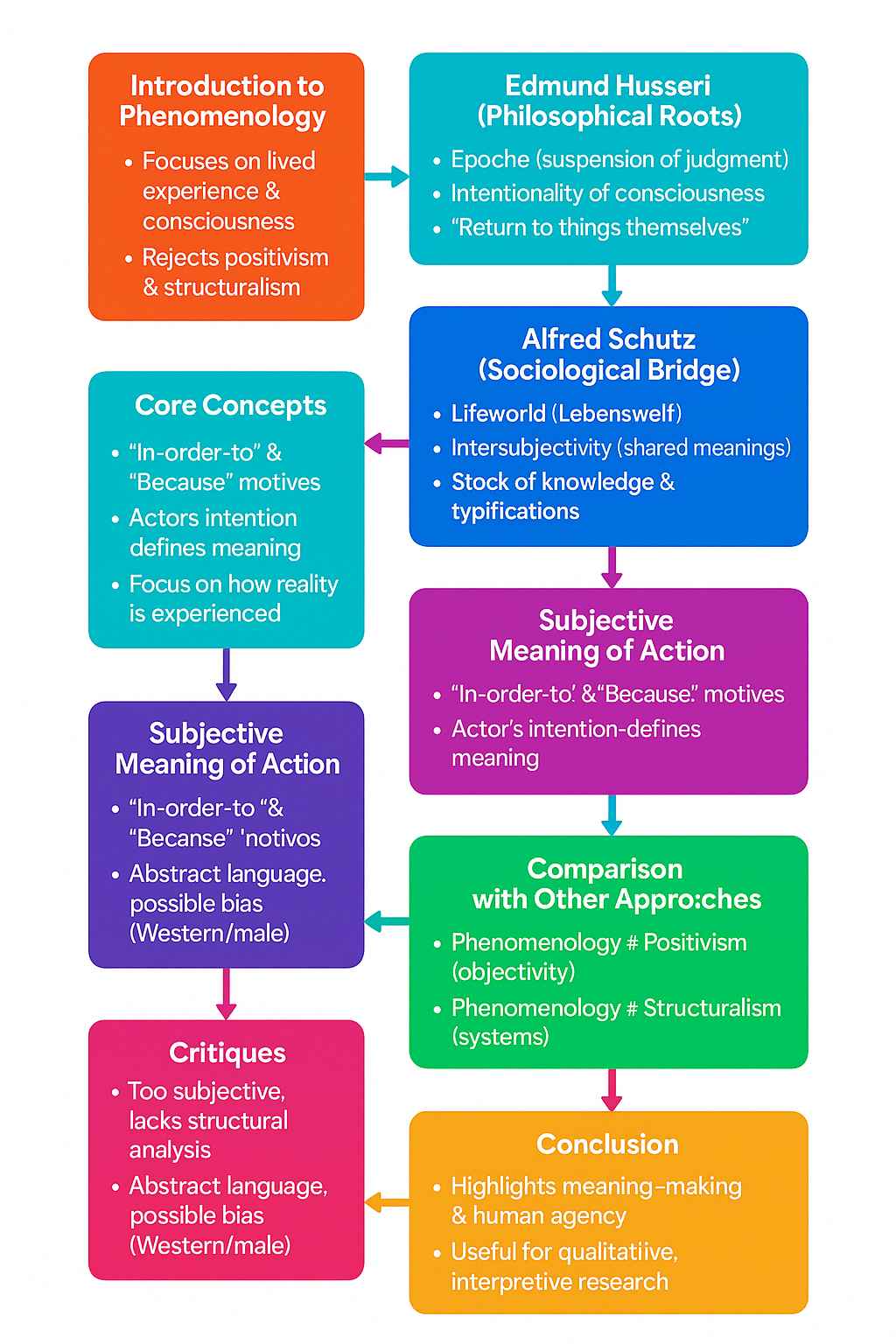

Introduction to Phenomenology

Phenomenology is both a philosophical movement and a methodological approach in the social sciences that seeks to understand the structures of experience and consciousness from the rst-person point of view. In sociology, phenomenology is used to explore how individuals construct meaning in their everyday lives. Unlike positivist approaches that seek objective facts or structuralist methods that focus on macro-level systems, phenomenology privileges the subjective and lived experiences of individuals. It investigates how people perceive, experience, and make sense of the social world—not through abstract theories, but through their situated, everyday practices. The central tenet of phenomenology is that reality is not something external or xed, but is continuously constituted in and through individual consciousness and interaction. Thus, phenomenology has become a powerful interpretive tool for understanding the micro-foundations of social life.

Philosophical Foundations: Edmund Husserl

The origins of phenomenology lie in the philosophical writings of Edmund Husserl, often regarded as the father of the movement. In his seminal work Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phenomenology (1913), Husserl proposed that scientific knowledge begins not with empirical data, but with the conscious experiences of individuals. He introduced the concept of epoché or phenomenological reduction, a method by which one suspends all preconceived notions and judgments about the external world in order to return to the “things themselves”—that is, the pure experience of phenomena as they appear to consciousness. For Husserl, consciousness is always intentional—it is always directed toward something—and it is through intentional acts that meaning is constituted. This was a radical break from both empiricism and rationalism, which treated consciousness as either a passive receiver or a logical machine. Husserl’s method laid the foundation for a new kind of science—one that studied the structures of experience rather than external behavior or facts.

Phenomenology and Sociology: Alfred Schutz

Phenomenology was brought into the realm of sociology primarily through the work of Alfred Schutz, an Austrian philosopher and social theorist who synthesized Husserl’s ideas with Max Weber’s interpretive sociology. Schutz argued that the social world is a world of meanings that individuals interpret and navigate using their stock of knowledge, habits, and typifications. He was particularly interested in the problem of how individuals make sense of the world as shared and intersubjective, even though their experiences are personal and subjective. In his work The Phenomenology of the Social World (1932), Schutz developed the idea that everyday life is structured around a “lifeworld” (Lebenswelt), the realm of taken-for-granted meanings and assumptions that individuals use to function smoothly in society. For Schutz, social action is not determined by external laws or rules, but by the interpretive acts of individuals who navigate a pre-interpreted world.

The Lifeworld and Intersubjectivity

One of the core concepts of phenomenological sociology is the lifeworld, a term borrowed from Husserl and elaborated by Schutz. The lifeworld refers to the world as it is experienced in everyday life, filled with familiar objects, routines, roles, and meanings. It is the background horizon that individuals rarely question but constantly rely upon. The lifeworld provides cognitive, moral, and practical structures that allow individuals to interpret new situations, categorize experiences, and interact with others meaningfully. Closely connected to this is the idea of intersubjectivity, the shared understandings and mutual recognition that make communication and cooperation possible. Intersubjectivity does not imply perfect consensus or identical experiences, but rather the assumption that others see the world “more or less” like we do. This assumption underpins all social interaction, from casual conversations to complex institutional processes. In this sense, phenomenology reveals that social reality is a shared construction that is continuously produced through the interaction of subjective perspectives.

Typifications and Social Knowledge

Schutz introduced the concept of typifications to explain how individuals make sense of the social world. Typifications are mental shortcuts or generalized categories that people use to classify people, events, and actions. For example, one might have typifications for “policeman,” “shopkeeper,” “student,” or “doctor”—each with a set of expected behaviors, roles, and norms. These typifications are not rigid stereotypes but exible mental schemas that allow individuals to function in complex social environments without being overwhelmed by detail. They are culturally and historically situated and are transmitted through language, education, and socialization. Typifications are essential because they enable pragmatic action—we do not have to analyze each situation from scratch; we rely on pre-existing knowledge that simplifies reality. However, typifications can also contribute to prejudice, exclusion, and power imbalances, when they are treated as natural or absolute rather than as socially constructed categories.

The Subjective Meaning of Action

Phenomenology places a strong emphasis on subjective meaning, a theme it shares with Max Weber’s notion of verstehen or interpretive understanding. For phenomenologists, human action cannot be understood solely through its external outcomes or functions. Instead, one must grasp the motive, intention, and context as interpreted by the actor. An action becomes “social” not because it follows a rule, but because it is directed toward others and involves an internal sense of meaning. Schutz distinguished between two types of motives: “because motives” (past-oriented reasons, like habits or experiences) and “in-order-to motives” (future-oriented goals or intentions). This dual structure allows sociologists to understand how individuals link their present actions to both past contexts and future aims. Thus, phenomenology offers a deep, layered understanding of social action, one that cannot be reduced to mere stimulus-response mechanisms or institutional roles.

Phenomenology vs Positivism and Structuralism

Phenomenology’s methodological orientation sharply contrasts with positivism, which seeks objective laws and universal truths based on observable data. It also diverges from structuralism, which posits that human behavior is governed by underlying structures like language, kinship, or economy. Instead, phenomenology adopts a constructivist and interpretive approach, focusing on how people experience, constitute, and negotiate reality. While positivists may seek to count instances of behavior, phenomenologists want to understand how that behavior is perceived, categorized, and imbued with meaning by the individual. Similarly, while structuralists may view individuals as products of abstract systems, phenomenologists see them as agents of meaning who creatively engage with and reshape those systems. Therefore, phenomenology shifts the focus of sociology from “what is society?” to “how is society experienced and made real in consciousness?”

Applications in Sociological Research

Phenomenology has been applied in various subelds of sociology to uncover the subjective dimensions of social life. In medical sociology, phenomenological approaches have been used to study the lived experience of illness, showing how patients interpret pain, diagnosis, or medical authority. In urban sociology, researchers have explored how people perceive and navigate public spaces, gentrication, or neighborhood identity. In gender and identity studies, phenomenology reveals how individuals construct their gender identity through embodied experience and social interaction. Phenomenology has also influenced ethnomethodology (via Harold Garnkel) and symbolic interactionism (via George Herbert Mead and Herbert Blumer). It has provided a methodological base for qualitative research methods such as in-depth interviews, participant observation, and narrative analysis. These methods align with phenomenology’s goal of uncovering meaning, rather than measuring behavior.

Critiques and Limitations of Phenomenology

Despite its contributions, phenomenology has faced several criticisms. Critics argue that it is too subjective, often relying on introspection or anecdotal data that cannot be generalized. Others suggest that it lacks attention to power, inequality, and structural constraints, making it ill-equipped to address systemic issues like racism, patriarchy, or capitalism. Marxist and critical theorists contend that phenomenology may overlook how ideology and domination shape individual consciousness, thus inadvertently reinforcing the status quo. Feminist scholars have also pointed out that the “universal subject” in classical phenomenology is often implicitly male, Western, and privileged. Moreover, phenomenological language can be dense and abstract, making it inaccessible to policy-makers or empirical researchers. Yet, defenders argue that phenomenology’s value lies precisely in its depth and nuance—its ability to illuminate the hidden textures of everyday life that are often ignored by more technical approaches.

Conclusion

Phenomenology has carved out a unique and enduring place within the sociological tradition. By focusing on lived experience, intentionality, and meaning-making, it has provided powerful insights into how social reality is produced, interpreted, and sustained. While its rejection of objectivist assumptions has drawn critique, phenomenology has enriched our understanding of human consciousness, interaction, and identity. Its legacy can be seen not only in specialized elds like interpretive sociology or qualitative research but also in broader debates about the nature of reality, the role of agency, and the possibility of understanding others. In an age of increasing complexity and fragmentation, phenomenology reminds us that at the heart of all social inquiry lies the need to grasp the world as it is lived and experienced by human beings. For students and scholars of sociology, phenomenology continues to oer a powerful toolkit for exploring the richness of everyday life.

References

- Husserl, Edmund. (1913). Ideas: General Introduction to Pure Phenomenology. New York: Macmillan.

- Schutz, Alfred. (1967). The Phenomenology of the Social World. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

- Berger, Peter L., and Luckmann, Thomas. (1966). The Social Construction of Reality. New York: Doubleday.

- Natanson, Maurice. (1970). Phenomenology, Role, and Reason: Essays on the Coherence of Social Life. Springeld, IL: Charles C. Thomas.

At the simplest level religion is the belief in the power of supernatural. These beliefs are present in all the societies and variations seem endless. A belief in the supernatural almost always incorporates the idea that supernatural forces have some influence or control upon the world. The first indication of a possible belief in the supernatural dates from about 60,000 years ago. Archaeological evidences reveal that Neanderthal man buried his dead with stone tools and jewellery.Religion is often defined as people's organized response to the supernatural although several movements which deny or ignore supernatural concerns have belief and ritual systems which resemble those based on the supernatural. However these theories about the origin of religion can only be based on speculation and debate.

Though religion is a universal phenomenon it is understood differently by different people. On religion, opinions differ from the great religious leader down to an ordinary man. There is no consensus about the nature of religion. Sociologists are yet to find a satisfactory explanation of religion.

Durkheim in his The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life defines religion as a unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things that is to say things set apart and forbidden. James G Frazer in his The Golden Bough considered religion a belief in powers superior to man which are believed to direct and control the course of nature and of human life.Maclver and Page have defined religion as we understand the term, implies a relationship not merely between man and man but also between man and some higher power. According to Ogburn religion is an attitude towards superhuman powers.Max Muller defines religion as a mental faculty or disposition which enables man to apprehend the infinite.

|

|

To answer the question how did religion begin – two main theories animism and naturism were advanced. The early sociologists, adhering to evolutionary framework, advocated that societies passed through different stages of development and from simplicity to complexity is the nature of social progress. The scholars who have contributed to the field of magic, religion and science can broadly be divided into four different types such as

- evolutionary scholars

- fundamentalist

- symbolic theorists

- analytical functionalists.

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|