Home >> Marriage Family and Kinship

Marriage in Indian Society

Index

- Introduction

- Defining Marriage: Classical and Sociological Perspectives

- Structural Functions of Marriage in Indian Society

- Marriage and Caste: Endogamy, Hypergamy, and Social Reproduction

- Patriarchy and Gender Roles in Marriage

- Religious Norms and Marriage Forms in India

- Economic Dimensions: Dowry, Property, and Women’s Labor

- Changing Trends in Indian Marriages

- Same-Sex and Queer Marriages: The Struggle for Recognition

- Law, State, and the Politics of Marriage

- Feminist and Critical Perspectives on Marriage

- Conclusion

Introduction

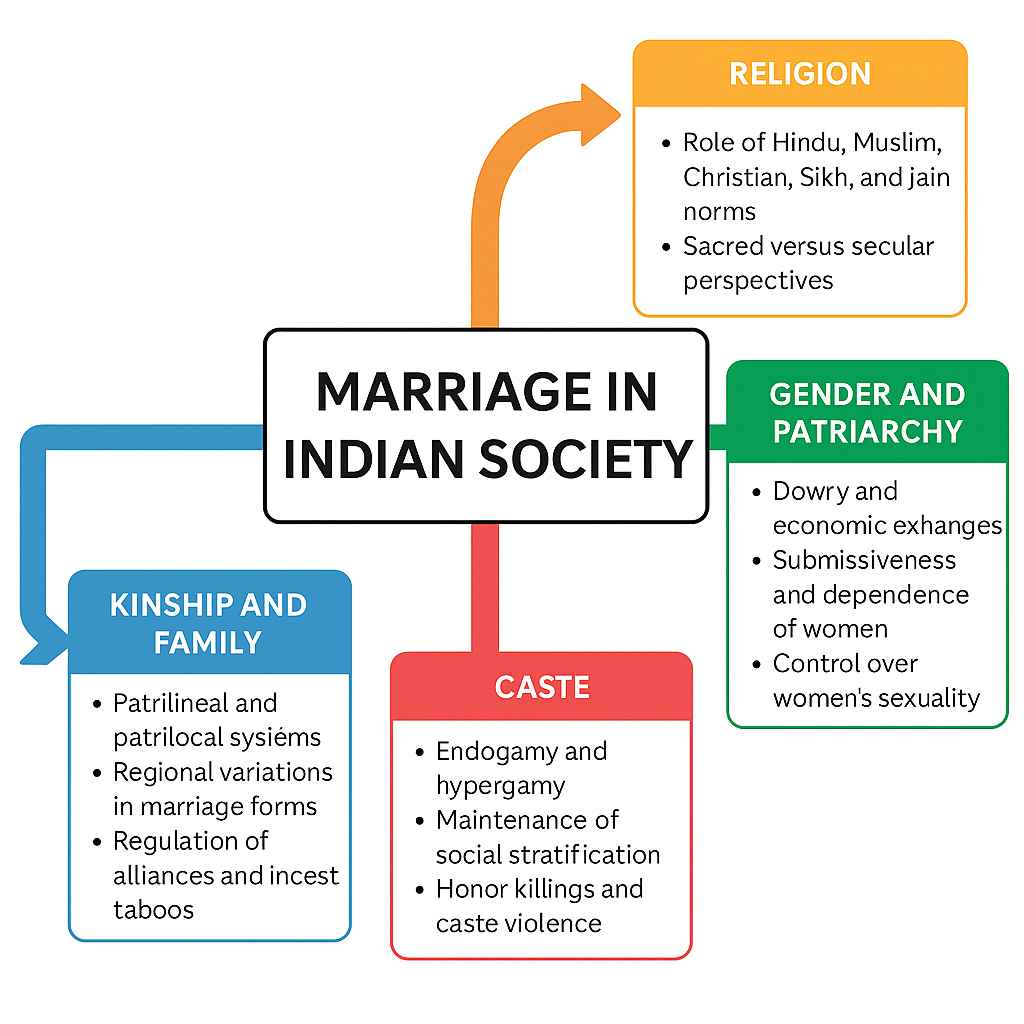

Marriage in India is far more than a personal decision or a romantic alliance between two individuals; it is a complex and foundational institution embedded deeply in the social fabric of Indian society. Through marriage, structures of caste, kinship, gender, religion, and economy are not only sustained but also actively reproduced. The institution serves as a microcosm of Indian society, reflecting its stratifications, hierarchies, values, and contradictions. It simultaneously serves as a site of social order and a locus of personal desire, community control, and even contestation. Unlike in many Western societies where marriage has gradually transitioned into a more individualistic and contractual model, in India, it continues to carry significant ritualistic, cultural, and familial weight. In this essay, we delve into marriage as a dynamic institution shaped by sociological theories, empirical studies, and legal practices, while also exploring its intersection with caste, class, gender, religion, and emerging forms of identity and expression.

Defining Marriage: Classical and Sociological Perspectives

The concept of marriage, though seemingly universal, has been subject to a variety of definitions across disciplines and cultures. In classical anthropological frameworks, marriage was often understood as a socially sanctioned union between a man and a woman that allowed for cohabitation, sexual relations, and the legitimization of offspring. George Peter Murdock, in his influential cross-cultural studies, defined marriage as “a universal institution that joins a man and a woman in a socially recognized relationship with the expectation of procreation, economic cooperation, and child-rearing.” However, such definitions have been critiqued for being rooted in heteronormative and patriarchal assumptions, neglecting diverse cultural patterns such as polygyny, polyandry, group marriage, and even celibate unions. Edmund Leach (1955) further nuanced the understanding by asserting that marriage often serves several functions—establishing legal paternity, legitimizing sexual access, granting rights over labor and property, and linking two kinship groups rather than merely individuals. These functions resonate profoundly in the Indian context, where the marriage bond extends beyond the conjugal dyad to include obligations and rituals involving extended families, caste councils, and religious communities.

Sociologically, marriage is not a monolithic structure but a fluid and culturally mediated institution. In India, thinkers such as Irawati Karve and A.M. Shah have provided rich ethnographic insights into how kinship and marriage patterns vary across regions. Karve, in her seminal work Kinship Organization in India (1953), emphasized the role of cross-cousin marriage in South India versus the strict exogamous rules in the North, which forbid marrying within the same gotra or clan. She argued that these regional kinship structures are not incidental but central to understanding the logic of marital alliances and the reproduction of social order. Meanwhile, A.M. Shah’s work on the household emphasized that marriage not only brings individuals together but also restructures the household and its economic and social dynamics. Marriage, therefore, is not simply a personal milestone but a pivotal node in the wider kinship network through which social structures—such as patriarchy, caste, and inheritance—are maintained.

From a theoretical standpoint, Emile Durkheim’s analysis in The Division of Labor in Society (1893) considers marriage as a means of moral regulation, reinforcing the collective conscience and stabilizing social relations. Functionalist perspectives, such as those advanced by Talcott Parsons, saw marriage as central to the nuclear family system, with clearly demarcated gender roles and a stabilizing effect on adult personalities. However, feminist and critical sociologists later challenged these assumptions, arguing that marriage often served to reproduce gender inequalities and reinforce patriarchal control. In India, feminist scholars like Nandita Haksar and Flavia Agnes have shown how marriage laws and customs operate not merely as private arrangements but as instruments of structural domination. These perspectives encourage us to interrogate marriage not just as a culturally unique practice, but as a site where power, identity, and resistance coalesce.

Structural Functions of Marriage in Indian Society

Marriage performs a range of structural functions that go far beyond individual relationships, acting as a mechanism to maintain societal stability, regulate sexuality, ensure lineage continuity, and manage economic resources. Drawing from structural-functionalist theory, particularly the work of Talcott Parsons and M.N. Srinivas, marriage in the Indian context can be seen as a nexus that binds multiple institutions—kinship, caste, economy, and religion—into a coherent but hierarchical social system. Parsons argued that the nuclear family, built on marital union, served two primary functions: socialization of children and stabilization of adult roles. However, in India, the joint family and extended kinship networks continue to be dominant, particularly in rural areas, where marriage creates ties not just between two individuals but between two larger family units. These ties are often meticulously negotiated through social rituals, dowry exchanges, and community consensus, ensuring that the alliance serves the strategic interests of the lineage groups involved.

One of the most significant social functions of marriage in India is the regulation of sexuality. In nearly all communities, marriage is considered the legitimate space for sexual relations and procreation. It is through marriage that individuals gain sexual legitimacy and that children are assigned patrilineal or matrilineal descent. This legitimization has profound implications for inheritance rights, ritual obligations, and family honor. The practice of arranged marriage—still dominant in much of India—serves not only to uphold these norms but also to ensure that alliances do not transgress caste, class, or religious boundaries. Arranged marriages are often orchestrated by parents and elders, reflecting a collectivist worldview in which the individual’s choice is subordinate to the family’s social positioning.

Sociologist Louis Dumont’s Homo Hierarchicus (1970) provides critical insight into how caste-based endogamy operates as a functional requirement within Indian society. For Dumont, the Indian social order is characterized by a hierarchical opposition between purity and pollution, and marriage is a key mechanism through which this hierarchy is preserved. Marriage, in this sense, becomes a ritual performance of social stratification, embedding individuals into a larger structure that governs not only their personal choices but also their religious and social duties. This perspective is further substantiated by ethnographic evidence from rural North India, where gotra exogamy and caste endogamy are strictly enforced by local community institutions such as khap panchayats. Violations often lead to sanctions, including social boycott or even honor killings, underscoring the continuing power of marriage as a regulatory institution in contemporary Indian society.

Marriage and Caste: Endogamy, Hypergamy, and Social Reproduction

Marriage is arguably the most powerful mechanism for the reproduction and consolidation of the caste system in India. As Dr. B.R. Ambedkar poignantly asserted in his classic text Annihilation of Caste (1936), caste survives through the institution of endogamy—the social rule that individuals must marry within their caste group. This system ensures not only the physical separation of caste groups but also their ideological and ritual distinctiveness. Endogamy prevents social mobility by locking women into rigid sexual and reproductive arrangements that safeguard the “purity” of upper-caste lineages. According to Ambedkar, the control over women’s sexuality and marital decisions is central to the preservation of caste. The family, in this context, becomes a site where the caste order is enforced, often through mechanisms of coercion, emotional pressure, and sometimes even violence.

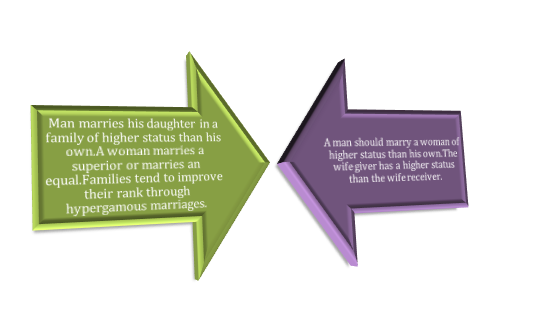

The phenomenon of caste endogamy is further complicated by the practice of hypergamy, particularly among upper castes. In hypergamous systems, women are expected to marry into equal or higher-status castes or sub-castes, while marrying “downward” is considered a social taboo. This practice reinforces not only caste hierarchy but also gender subordination, as women’s value is tied to their ability to “marry up” and thereby improve their family’s social status. M.N. Srinivas’s theory of Sanskritization offers additional insight into these dynamics. He noted that lower castes often seek to elevate their status by adopting upper-caste practices—such as vegetarianism, ritual purity, and dowry systems—but are generally excluded from inter-caste marital alliances. Even when such alliances occur, they tend to be highly asymmetrical, with upper-caste men marrying lower-caste women (hypergamy) more frequently than the reverse. This preserves the male-dominated logic of caste reproduction while appearing to accommodate limited social mobility

Empirical evidence confirms the rigidity of caste-based marriage patterns in contemporary India. According to data from the Indian Human Development Survey (IHDS) and the 2011 India Census, over 90% of marriages are still conducted within the same caste, despite increased urbanization, education, and exposure to modern values. Sociological studies such as those by Surinder S. Jodhka and Ghanshyam Shah further reveal that even in urban areas and among educated classes, caste continues to be a key criterion in spouse selection. Matrimonial websites like Shaadi.com and Jeevansathi.com include caste and sub-caste as primary filters, showing how digital platforms are also being mobilized to preserve traditional boundaries.

Tragically, the social consequences of violating caste endogamy can be severe. Honor killings, especially in North Indian states like Haryana, Punjab, and Uttar Pradesh, are often linked to inter-caste marriages. The infamous case of Manoj and Babli in 2007, a young couple who married within the same gotra and were brutally murdered by their family members under the sanction of a khap panchayat, shocked the nation and highlighted how deep-rooted the caste logic in marriage remains. More recently, the 2013 killing of Ilavarasan, a Dalit youth who married a Vanniyar (OBC) girl in Tamil Nadu, sparked national debates on caste violence and the politics of love and marriage. These cases illustrate that while inter-caste marriages are legal under the Special Marriage Act, 1954, they often lack social sanction and are fiercely resisted by casteist structures that view such unions as threats to community honor and purity.

Patriarchy and Gender Roles in Marriage

Marriage in India is deeply implicated in the reproduction of patriarchal norms, values, and power relations. It is a key institution through which gender roles are assigned, reinforced, and justified. The dominant model of marriage is patrilineal and patrilocal, meaning that upon marriage, women are expected to move into their husband’s household and assume a subordinate role within that domestic unit. This shift entails not only physical relocation but also a transformation of identity, as women are often expected to change their surname, dress, religious practices, and even food habits to conform to their husband’s family culture. Such transformations are emblematic of the broader patriarchal logic that defines women primarily in relation to men—as daughters, wives, and mothers—rather than as autonomous individuals.

One of the most striking features of gendered inequality in Indian marriage is the enduring practice of dowry. Although officially outlawed by the Dowry Prohibition Act of 1961, dowry continues to be widespread, especially among middle and upper-caste Hindus. It is rationalized as a form of pre-mortem inheritance or a gift to the bride, but in practice, it often becomes a financial transaction that commodifies women and places enormous pressure on their natal families. The demand for dowry leads to economic burdens, delayed marriages, female foeticide, and, in extreme cases, dowry-related violence and deaths. Scholars like Veena Talwar Oldenburg have shown that dowry became more commercialized during colonial times due to legal and administrative changes, transforming what were once customary gifts into coercive demands. Today, dowry serves not only as an economic exchange but as a symbolic assertion of male dominance and control over women’s bodies and labor.

Feminist sociologists such as Leela Dube and Sharmila Rege have emphasized how marriage operates as a disciplinary institution that enforces heterosexuality, restricts women’s mobility, and regulates reproductive labor. Leela Dube, in her ethnographic studies, highlighted how gendered socialization begins from childhood and culminates in marriage, where women are taught to serve, obey, and sacrifice. Sharmila Rege critiqued the Hindu Code Bills for reinforcing the ideal of the pativrata (dutiful wife) and privileging the upper-caste woman’s experience as normative, thereby marginalizing the concerns of Dalit and Bahujan women. These insights challenge the romanticized notion of marriage as a relationship of mutual care, instead exposing it as a site of unequal labor distribution, emotional servitude, and legal vulnerability

The gendered division of labor within marriage is another critical issue. In most Indian households, women are responsible for all forms of unpaid labor, including cooking, cleaning, child-rearing, eldercare, and emotional management. Even when women are employed outside the home, they continue to bear the burden of domestic work, a phenomenon termed the “double burden.” Economists like Devaki Jain and Bina Agarwal have called attention to the invisibility of women’s unpaid labor in national accounting systems and policy frameworks. Sociologically, this underscores how marriage functions not merely as a site of emotional or sexual companionship but as a mechanism for the appropriation of female labor without compensation or recognition

Religious Norms and Marriage Forms in India

Religious traditions play a foundational role in shaping the norms, rituals, and legal frameworks surrounding marriage in India. Unlike in many secular societies where marriage is primarily a civil contract, in India, marriage is often viewed as a sacred and divinely sanctioned union. The cultural and legal architecture of Indian marriages is deeply intertwined with religion, resulting in varied practices and forms across Hindu, Muslim, Christian, Sikh, Jain, and tribal communities. This diversity reflects not only the pluralism of Indian society but also the complexity of regulating personal law within a democratic, secular state. At the same time, religious ideologies often serve to legitimize hierarchical and patriarchal structures within marriage, making it a contested and dynamic domain.

Among Hindus, marriage (vivaha) is considered a sacrament (sanskara)—not merely a social contract but an indissoluble bond that links two souls across lifetimes. This worldview is embedded in the Dharmashastras, particularly the Manusmriti, which outlines the ideal roles of husband and wife and sanctifies the authority of the husband over his spouse. According to Hindu law prior to the Hindu Code reforms, marriage could not be dissolved, and the husband wielded significant control over decisions related to property, movement, and sexuality. Even today, Hindu marriage ceremonies involve elaborate rituals like the saptapadi (seven steps), kanyadaan (giving away of the daughter), and mangal sutra (sacred thread), which symbolically and materially position the woman as subordinate and transferred property. Scholars like Uma Chakravarti have critiqued these rituals for their role in legitimizing Brahmanical patriarchy—a system that combines caste and gender hierarchies to ensure purity, lineage, and control over women’s sexuality.

In contrast, Islamic law treats marriage (nikah) as a civil contract (mua’malat) rather than a sacrament. It includes provisions for negotiation, consent, and the financial rights of the wife through mehr (mandatory bridegift). While theoretically offering more gender equity in matters of divorce and inheritance, in practice, patriarchal customs often dilute these provisions. The practice of triple talaq (instant divorce), though declared unconstitutional in 2017 by the Supreme Court, exposed how religious interpretation can be manipulated to subordinate women. Muslim women’s rights activists like Shah Bano and contemporary voices like Zakia Soman have advocated for reforms that retain the spirit of Islamic egalitarianism while challenging patriarchal distortions within personal law.

Christian marriages in India are governed by the Indian Christian Marriage Act of 1872, a colonial-era legislation that formalizes the sacramental character of marriage. Divorce among Christians was historically restricted to adultery, and even today, annulment processes are often slow and stigmatizing. Sikh and Jain marriages follow respective cultural traditions, with Sikh marriages formalized through the Anand Karaj ritual. Tribal communities across India also practice diverse forms of marital unions—including trial marriages, bride service, and sororate or levirate systems—that reflect both their indigenous ethos and the pressures of assimilation into dominant religious paradigms.

An important secular alternative is offered by the Special Marriage Act of 1954, which enables individuals of different religions or castes to marry without converting. It provides for civil marriage, divorce, and inheritance irrespective of religion. However, this act, too, is fraught with social and administrative challenges. Couples often face harassment from families, police, and even court officials. The requirement to give public notice 30 days before the wedding has led to surveillance and intimidation, particularly in cases of interfaith or inter-caste marriages. As such, the religious framework of marriage in India continues to be both a resource and a constraint—providing symbolic and emotional meaning to relationships while simultaneously reproducing social hierarchies.

Economic Dimensions: Dowry, Property, and Women’s Labor

Marriage in Indian society is not merely a social or cultural affair—it is also an economic transaction, deeply embedded in systems of property, inheritance, and labor. The economic dimension of marriage has historically been structured in a way that benefits men and their families, while often dispossessing women of property and agency. From the institution of dowry to the invisibility of women’s unpaid domestic labor, marriage plays a central role in maintaining gendered divisions of wealth and work.

One of the most discussed economic aspects of Indian marriage is the practice of dowry, which involves the transfer of cash, goods, and property from the bride’s family to the groom’s. Despite being criminalized under the Dowry Prohibition Act (1961), dowry remains pervasive, particularly among the upper castes and middle classes. It has become both a status symbol and a financial negotiation, with the groom’s education, profession, and family background serving as bargaining chips. Scholars like Veena Oldenburg have traced the historical transformation of dowry during colonial rule, when British legal reforms dismantled women’s rights to land and inheritance and replaced them with a cash-based dowry economy. Dowry deaths, harassment, and suicides—reported widely in both rural and urban areas—are symptoms of this system, which treats women as liabilities and burdens.

Women’s exclusion from property rights further exacerbates their vulnerability within marriage. While the Hindu Succession Act of 2005 gave daughters equal rights to ancestral property, implementation remains patchy due to cultural resistance, lack of awareness, and familial coercion. In most parts of India, women continue to forgo their share of land or property in favor of male siblings or as a condition of marital harmony. In Muslim personal law, women are legally entitled to inheritance, but their share is often significantly smaller than that of men, and social pressures often prevent women from claiming even that. This economic dispossession makes women financially dependent on their husbands and in-laws, reducing their ability to negotiate or exit from oppressive marital arrangements.

A less visible but equally critical issue is the appropriation of women’s labor within marriage. The vast amount of unpaid domestic work—cooking, cleaning, caregiving, emotional support—performed by wives is treated as a “duty” rather than as productive labor. Feminist economists like Marilyn Waring, Devaki Jain, and Bina Agarwal have long argued that national GDP calculations and economic policy frameworks exclude this unpaid labor, thereby rendering women’s work invisible. In India, time-use surveys consistently show that women spend significantly more hours than men on domestic and care work, even when they are also engaged in formal employment. Marriage, in this context, functions as an institution that extracts labor without compensation, under the guise of love, duty, or sacrifice.

Dowry, inheritance, and labor together form a triad through which economic control is exerted within marriage. This control is gendered, classed, and caste-specific, meaning that its effects vary depending on the socio-economic location of the woman. For instance, a Dalit woman married into a landless household may be subjected to a different kind of economic exploitation than an upper-caste woman in an elite family—but both experiences reveal how marriage is not only about companionship but also about economic power.

Changing Trends in Indian Marriages

While tradition continues to shape the institution of marriage in India, there has been a noticeable shift in patterns, practices, and perceptions in recent decades—driven by urbanization, education, globalization, feminist movements, and digital technologies. These changes do not dismantle the core structure of marriage entirely but produce significant ruptures that warrant sociological attention. New trends include the rise of love marriages, inter-caste and inter-religious unions, delayed marriages, cohabitation, and growing autonomy among women, particularly in urban settings.

One of the most visible changes has been the gradual shift from arranged to love marriages, especially among urban youth. Although arranged marriages remain dominant, surveys like those conducted by the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) and the India Human Development Survey (IHDS) show a steady increase in love marriages or hybrid models where choice is exercised within the boundaries of parental approval. This transition reflects changing value orientations influenced by exposure to liberal education, popular media, and the growing importance of personal compatibility and emotional fulfillment in spousal relationships. Sociologist Patricia Uberoi notes that Bollywood has played a crucial role in popularizing the “romantic love” ideal, though it is often still embedded within familial and heteronormative frameworks.

Digital technologies have also transformed the landscape of marriage. Matrimonial websites like Shaadi.com and Bharat Matrimony have digitized the practice of matchmaking, allowing individuals to search for partners across regions and castes while filtering for religion, income, education, and even skin tone. These platforms create an illusion of personal choice but often reinforce social stratification through caste filters and economic preferences. On the other hand, dating apps like Tinder and Bumble are introducing new scripts of intimacy and pre-marital interaction, particularly among middle-class urban youth. While these platforms may not always lead to marriage, they signal a broader redefinition of how relationships are initiated, negotiated, and navigated.

Delayed marriage is another significant trend. With increasing participation of women in higher education and the workforce, the age at which individuals marry—especially in urban areas—has risen. According to NFHS-5 (2019–21), the median age at marriage for women in urban India is now close to 22, up from 19 a decade ago. This delay is not merely a demographic trend but also reflects a desire among women to establish financial independence, pursue careers, and expand their life choices before entering into marriage. Feminist scholars see this as a potential site of resistance, where women assert agency over the timing and terms of their marital relationships.

Yet, this transition is uneven. In rural areas and among lower-income groups, early and child marriages still persist, driven by poverty, patriarchy, and lack of access to education. The persistence of child marriage, despite legal prohibitions under the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act (2006), highlights the gap between legal reform and social reality. Furthermore, there is a growing backlash against non-traditional marriages—manifested in moral policing, honor killings, and state interventions like the proposed “love jihad” laws targeting interfaith couples. These reactions illustrate that while marriage is changing, it remains a battleground for competing ideologies of modernity, tradition, and identity

Same-Sex and Queer Marriages: The Struggle for Recognition

One of the most radical challenges to the heteronormative institution of marriage in

India comes from queer and LGBTQIA+ communities. Marriage has historically

been framed as a union between a man and a woman, with assumptions of

reproductive intent and gender complementarity. The growing visibility and activism

of queer individuals and collectives, however, has questioned this foundational

assumption, demanding recognition, dignity, and rights for non-heterosexual

partnerships.

Until 2018, same-sex relationships were criminalized under Section 377 of the Indian

Penal Code, a colonial-era law that treated such acts as “against the order of nature.”

The landmark Supreme Court judgment in Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India

(2018) decriminalized homosexuality and recognized the rights of LGBTQ

individuals to dignity, privacy, and equality. However, this decriminalization did not

extend to marriage rights. Same-sex couples in India remain outside the ambit of

personal laws and the Special Marriage Act, and are denied legal recognition,

inheritance, adoption, and spousal benefits.

Sociologists and queer theorists argue that marriage in its current legal and cultural

form is structured around heteronormativity and patriarchal kinship. Gayatri Reddy

and Naisargi Dave, for instance, show how queer relationships in India often operate

outside formal institutions, relying on networks of care, friendship, and chosen

families. While some LGBTQ activists seek legal inclusion within existing

frameworks of marriage, others are critical of the very institution, arguing that it is

built on exclusion, control, and normative expectations. They propose alternative

forms of recognition that value intimacy, commitment, and care without the

trappings of legal contract or social respectability.

In 2023, a series of petitions seeking the legalization of same-sex marriage reached the

Supreme Court. The debates around these cases revealed deep societal anxieties

about the “erosion” of traditional values, the definition of family, and the role of the

state. The judgment, while recognizing the fundamental rights of queer individuals,

stopped short of legalizing same-sex marriage, deferring the matter to the legislature.

This decision disappointed many in the queer community but also sparked wider

conversations about plural forms of intimacy and the need to democratize family

structures.

Same-sex and queer marriages thus challenge not only legal norms but also cultural

assumptions about what constitutes love, partnership, and kinship. They force

Indian society to confront the limits of its inclusivity and to imagine new

possibilities beyond the heterosexual, reproductive, caste-endogamous family unit.

Law, State, and the Politics of Marriage

Marriage in India is not just a cultural and social event—it is also a profoundly legal institution shaped by colonial legacies, post-independence reforms, and ongoing political struggles. The legal regulation of marriage operates through a complex interplay of personal laws, secular laws, and judicial interpretations that often reflect majoritarian and patriarchal assumptions. Each religious community in India is governed by its own personal law: Hindu marriage is governed by the Hindu Marriage Act (1955), Muslim marriages are regulated under Muslim Personal Law (Shariat), Christians follow the Indian Christian Marriage Act (1872), and Parsis follow the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act (1936). For interfaith couples or those seeking civil marriage without religious rites, the Special Marriage Act (1954) exists as an alternative—but one that is not free from bureaucratic and social hurdles.

The Hindu Marriage Act was a landmark in attempting to codify customary practices, but it also entrenched upper-caste Brahmanical values by enforcing monogamy, outlining conditions for valid marriage, and specifying grounds for divorce. While it introduced provisions for women’s rights such as divorce and maintenance, in practice, patriarchal interpretations still dominate courtrooms and social attitudes. Feminist legal scholars like Flavia Agnes have criticized Indian marriage laws for privileging the heterosexual, reproductive, and patriarchal family unit. Even progressive provisions often fail to protect women from dowry violence, marital rape (still not criminalized in India), or economic dependency after divorce.

Muslim Personal Law, by contrast, treats marriage as a civil contract (nikah) and

allows for polygyny. Women’s rights activists within the Muslim community have

long pointed out both the empowering and oppressive aspects of this system. The

controversial issue of triple talaq (instant divorce) became a flashpoint for legal

intervention. In Shayara Bano v. Union of India (2017), the Supreme Court declared

triple talaq unconstitutional, a decision welcomed by many women but also criticized

for being driven more by Hindu nationalist politics than genuine concern for gender

justice.

The Special Marriage Act (SMA) was envisioned as a secular, egalitarian alternative

to religious personal laws. However, it includes a provision that requires couples to

publicly declare their intent to marry 30 days in advance—a clause that has been

weaponized by vigilante groups to harass inter-caste and interfaith couples,

particularly under the pretext of “love jihad.” The politics of marriage thus becomes

intertwined with the politics of religion, caste, and gender. Scholars like Nandini

Sundar and Surabhi Shukla argue that the state’s control over marriage reflects its

desire to regulate social reproduction, maintain caste boundaries, and uphold

heteronormative patriarchy.

Legal reform alone is not sufficient to challenge these structures. As B.R. Ambedkar

powerfully asserted in Annihilation of Caste, the most effective way to break caste is

through inter-caste marriage. Yet, such marriages remain rare and socially

stigmatized. The state’s failure to protect couples from honor killings or to provide

safe housing for inter-caste and interfaith marriages reveals the limits of liberal legal

frameworks. Marriage, far from being a private affair, becomes a site where the state

actively regulates social mobility, moral norms, and community boundaries.

Feminist and Critical Perspectives on Marriage

Feminist theory has profoundly reshaped the sociological understanding of marriage, exposing it not merely as a personal or cultural practice, but as a deeply political institution that upholds gendered power relations. Radical feminists such as Shulamith Firestone and Kate Millett viewed marriage as the central site of women’s oppression, where their labor, sexuality, and autonomy are controlled by patriarchal norms. In the Indian context, feminist scholars have demonstrated how marriage reinforces gender hierarchies through practices like dowry, patrilocal residence, control over women’s mobility, and expectations of unpaid domestic labor.

Marriage, in most Indian communities, is patrilocal—women leave their natal homes

to live with their husband’s family. This often results in severance from their kin,

economic disempowerment, and reduced agency. Women are expected to adapt,

compromise, and serve—not just their husbands, but in-laws as well. Household

labor is naturalized as a feminine duty, and emotional labor becomes the unseen glue

holding the marital bond together. The concept of seva (selfless service) becomes a

moral expectation, romanticized in cultural scripts but exploitative in reality.

Feminist ethnographies, such as Rukmini Sen’s work on domesticity, reveal how the

ideal Indian wife is constructed through daily acts of deference, sacrifice, and silence.

Dowry, while officially outlawed through the Dowry Prohibition Act (1961),

continues to be a pervasive part of marriage negotiations, particularly in North India.

It reinforces women’s status as economic burdens who must be “compensated” for.

Dowry-related violence—including threats, emotional abuse, and even bride

burning—exposes the brutal underside of an institution that is often idealized as

sacred and eternal. Scholars such as Veena Talwar Oldenburg have shown how dowry

is not simply a “tradition” but a modern phenomenon shaped by colonial legal

systems and middle-class aspirations. It is often used to acquire capital, settle

property claims, or enhance status—transforming marriage into a transactional

market.

Feminist movements in India have challenged these dynamics both through grassroots organizing and legal activism. The campaign against dowry, the demand for criminalizing marital rape, the struggle for women’s inheritance rights, and the fight against honor killings are all efforts to deconstruct the power relations embedded within marriage. At the same time, intersectional feminists remind us that experiences of marriage differ across caste, class, and religion. Dalit and Adivasi women, for instance, may face different forms of control and violence, while also being denied the respectability that marriage is supposed to confer

Thus, feminist and critical sociological perspectives compel us to see marriage not as a benign or universal institution but as a site of negotiation, resistance, and transformation. They push for not only reform but also re-imagination—towards partnerships that are based on consent, equality, and care, rather than control, hierarchy, and compulsion.

Conclusion

Marriage in Indian society is a complex, layered, and deeply contested institution. It is at once sacred and strategic, emotional and economic, personal and political. It operates at the intersection of kinship, caste, religion, gender, and law—shaping and reflecting the larger social order. While it is often celebrated as a rite of passage and a symbol of cultural continuity, it also enforces conformity, perpetuates inequality, and resists change.

Sociological inquiry into marriage must therefore move beyond normative assumptions to critically examine how it functions, whom it serves, and how it can be transformed. The institution is not static—it is continually being reshaped by social movements, legal struggles, economic shifts, and changing aspirations. Love marriages, queer unions, inter-caste relationships, delayed marriages, and digital courtships all signal new configurations that both challenge and coexist with tradition.

In rethinking marriage, the goal is not to dismiss its significance, but to imagine it differently: as a space of mutual respect, shared labor, and democratic partnership. This vision remains aspirational, but sociological engagement must illuminate the path toward it—by exposing power, amplifying voices, and insisting on justice at the heart of intimacy.

References

- Ambedkar, B.R. (1936). Annihilation of Caste.

- Agnes, Flavia (2000). Law and Gender Inequality

- Dumont, Louis (1970). Homo Hierarchicus.

- Karve, Irawati (1953). Kinship Organization in India.

- Leach, Edmund (1955). “Polyandry, Polygyny and the Function of Marriage.” Man

- Murdock, George Peter (1949). Social Structure

- Oldenburg, Veena Talwar (2002). Dowry Murder: The Imperial Origins of a Cultural Crime.

- Parsons, Talcott (1955). “The American Family: Its Relations to Personality and the Social Structure.” Family, Socialization and Interaction Process.

- Shah, A.M. (1998). The Family in India: Critical Essays.

- Uberoi, Patricia (1993). Family, Kinship and Marriage in India

- Reddy, Gayatri (2005). With Respect to Sex: Negotiating Hijra Identity in South India.

- Sen, Rukmini (2005). “The Feminization of Domesticity in Indian Middle-Class Families.” Indian Journal of Gender Studies.

Marriage

It has been generally assumed that the institution of marriage is a universal feature in human societies. Although many sociologists and anthropologists have attempted to provide definitions of marriage, none of them has been satisfactorily and sufficiently general enough to encompass all its various manifestations. This is because marriage is a unique institution of human society that has different implications in different cultures. It is a biological fact that marriage is intimately linked to parenthood. This has led to many anthropologists like Malinowski and Radcliffe-Brown to propose definitions of marriage centering on the Principle of Legitimacy.

According to Malinowski, a legal marriage is one which gives a woman a socially recognized husband and her children a socially recognized father.

Radcliffe-Brown states that Marriage is a social arrangement by which a child is given a legitimate position in the society determined by parent hood in the social sense.

According to Westermarck it is a relation of one or more men to one or more women which is recognized by custom or law and involves certain rights and duties both in the case of parties entering the union and in the case of children born out of this union.

According to Lundberg, marriage consists of rules and regulations that define the rights, duties and privileges of husband and wife with respect to each other.

According to Horton and Hunt marriage is the approved social pattern whereby two or more persons establish a family.

According to John Levy and Ruth Monroe people get married because of the feeling that being in a family is the only proper indeed the only possible way to live. People do not marry because it is their social duty to perpetuate the institution of family or because the scriptures recommend matrimony but because they lived in a family as children and cannot get over the feeling that being in a family is the only proper way to live in society.

Edmund Leach argued that the institutions commonly classed as marriage are concerned with the allocation of a number of distinguishable classes of rights and hence may serve to do any or some or all of the following.

- To establish the legal father of a woman's children.

- To establish the legal mother of a man's children.

- To give a husband a monopoly of the wife's sexuality.

- To give the wife a monopoly of the husband's sexuality.

- To give the husband partial or monopolistic rights to the wife's domestic and other labor services.

- To give the wife partial or monopolistic rights to the husband's domestic and other labor services.

- To give the husband partial or total rights over property belonging or potentially accruing to the wife.

- To give the wife partial or total rights over property belonging or potentially accruing to the husband.

- To establish a joint fund of property – partnership for the benefit of the children of the marriage.

- To establish a socially significant relationship of affinity between the husband and his wife's brothers.

It is clear from different definitions that it is only through the establishment of culturally controlled and sanctioned marital relations that a family comes into being. The institutionalized form of these relations is called marriage. Marriage and family are two aspects of the same social reality that is recognized by the world. Anderson and Parker say that wedding is the recognition of the significance of marriage to society and to individuals through the public ceremony usually accompanying it. Such a ceremony indicates the society's control.

Anthropological studies of marriage have brought out complex marriage systems .In the Nuer ghost marriage a woman marries a woman. In another form of marriage a widow either remarries or takes lovers. The children born to her are considered as a legitimate offspring of her dead husband. In yet another form of marriage among the Nuer a woman marries another senior woman. Children born to the junior woman because of the links with a lover are considered to be the members of the husband’s patrilineage. In the matrilineal Nair society in Kerala, young girls were married ceremoniously but did not reside with their husbands. The girls were permitted to take lovers with whom they bore children. Neither the husbands nor the lovers had right over the children who became the members of their mother’s lineage.

Hypergamy and Hypogamy

The norm in Hypergamy is that a man should marry his daughter in a family of higher status than his own. In a hypergamous marriage a woman marries a superior or an equal; a man should not marry a woman of higher status than himself. Though Hypergamy is prevalent in India it is not universal. In classical Hindu ideology the bride is considered as a gift or dan. In addition gifts in terms of dowry and materials are also given. The hierarchical relationship between the wife giver and wife receiver may be expressed in commensal activities. Families by adopting hypergamous marriages may improve their rank. Hypergamous marriages when repeated by wife givers and wife receivers may lead to consolidation of affinal relationship.

The norm in hypogamous system is that a man should marry a woman of higher status than his own. In such a case the wife giver has a higher status than the wife receiver. Such a type of marriage has been chronicled in Myanmar where commoners married women of aristocratic lineages.

|

|

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|