Home » Social Thinkers » Sir Edward Burnett Tylor

Sir Edward Burnett Tylor

Table of Contents

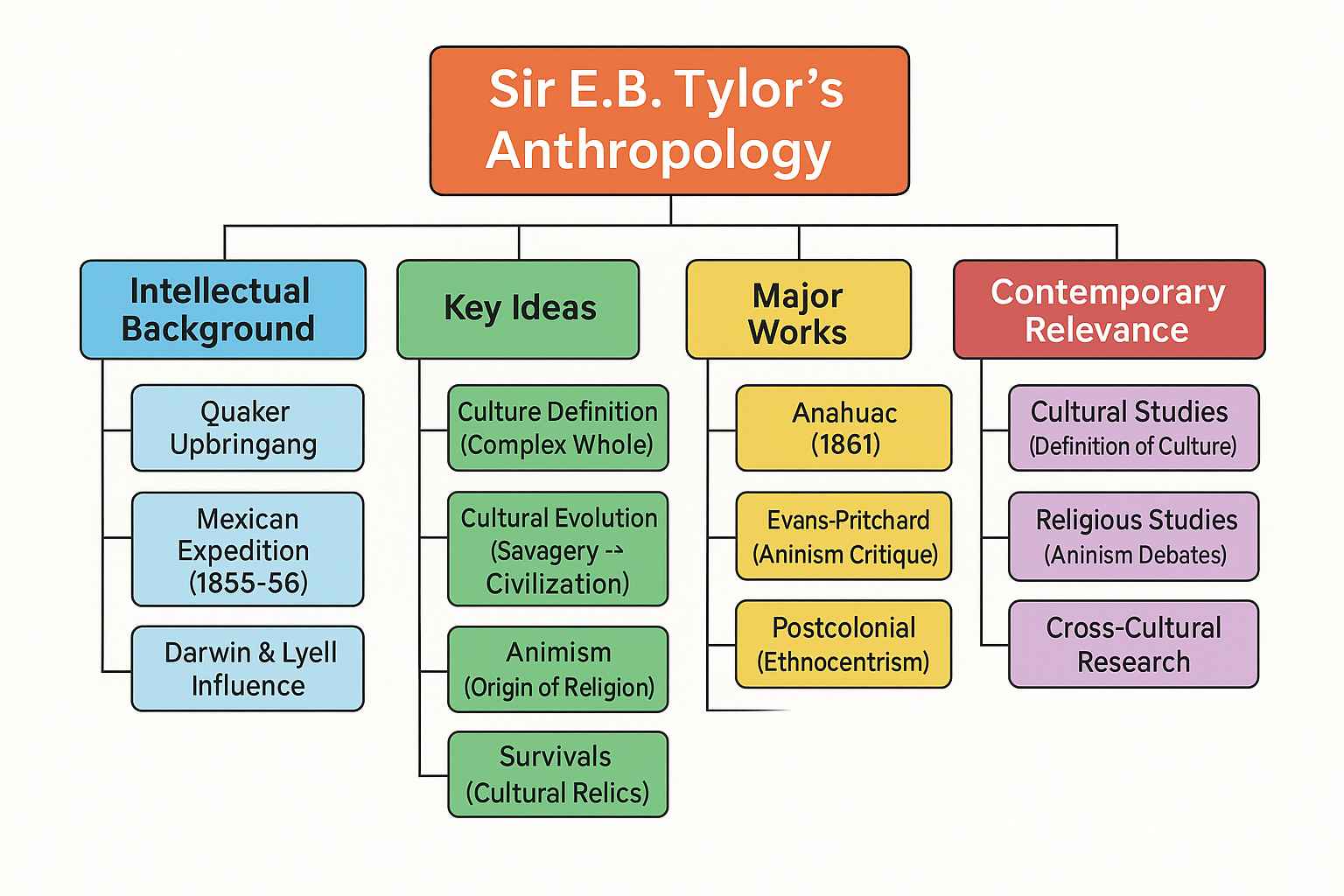

Introduction and Intellectual Background

Sir Edward Burnett Tylor (1832–1917), oen hailed as the founder of cultural anthropology, was a pivotal figure in establishing anthropology as a scientific discipline. Born on October 2, 1832, in Camberwell, London, to a prosperous Quaker family that owned a brass foundry, Tylor grew up in a socially progressive yet religiously disciplined environment. His early education at Grove House School, a Quaker institution in Tottenham, emphasized intellectual rigor but excluded him from university due to his faith, which barred Quakers from attending Oxford or Cambridge. At 16, aer his parents’ death, Tylor joined the family business, but tuberculosis at age 23 prompted a journey to warmer climates, sparking his anthropological interests. In 1855, while traveling in the Americas, he met Henry Christy, a Quaker ethnologist and archaeologist, whose mentorship during a six-month expedition in Mexico profoundly shaped Tylor’s career. This experience, detailed in his first book, Anahuac (1861), ignited his fascination with cultural differences and prehistoric societies. Influenced by the Scientific Revolution, particularly Charles Darwin’s evolutionary theory and Charles Lyell’s uniformitarianism, Tylor adopted a rationalist, evolutionary framework, rejecting the metaphysical leanings of his Quaker upbringing while retaining its humanitarian ethos. His exposure to Enlightenment thinkers like Auguste Comte and Herbert Spencer, alongside classical scholarship, further informed his belief in universal human progress. Tylor’s career flourished in England, where he married Anna Fox in 1858 and settled in Wellington, Somerset. His academic ascent culminated in his appointment as the first professor of anthropology at Oxford University (1896–1909), aer serving as a reader (1884) and keeper of the University Museum (1883). His armchair approach, relying on comparative data rather than fieldwork, reflected the era’s intellectual climate, blending Victorian rationalism with a commitment to understanding human culture’s evolution. Tylor’s interdisciplinary synthesis of science, history, and ethnology laid the groundwork for modern anthropology, earning him a knighthood in 1912.

Key Ideas and Concepts

Tylor’s philosophy is best known for his theory of cultural evolution and his foundational definition of culture, which remain influential in anthropology. In Primitive Culture (1871), he defined culture as “that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society,” providing a holistic framework still used today. This definition emphasized culture as learned, not biologically inherited, and universal across human societies, countering racial hierarchies prevalent in his time. Central to Tylor’s thought is cultural evolutionism, which posits that all societies progress through three stages—savagery, barbarism, and civilization—in a unilinear trajectory driven by rational thought and technological advancement. Influenced by Darwin, Tylor argued that human culture evolves from simple to complex forms, with all societies sharing a uniform psychic nature, meaning a hunter-gatherer possesses the same intellectual potential as a modern individual, differing only in accumulated knowledge. His concept of “survivals” describes archaic beliefs or practices, like superstitions, that persist in modern societies as relics of earlier stages, offering clues to cultural history. Tylor’s theory of animism, which he reintroduced, posits that the earliest form of religion arose from primitive attempts to explain phenomena like death and dreams, attributing souls or spirits to living and inanimate objects. He viewed animism as the foundation of all religions, evolving into polytheism and monotheism as societies advanced. Tylor’s comparative method, using data from diverse cultures to reconstruct human history, assumed that contemporary “primitive” societies mirrored prehistoric ones, enabling historical insights without direct evidence. His emphasis on rationalism and progress reflected his Quaker-inspired belief in human unity and his rejection of theological explanations, positioning anthropology as a tool to eliminate irrational survivals and promote societal reform. These ideas, rooted in Victorian optimism, established Tylor as a pioneer in analyzing culture systematically.

Major Works and Their Explanations

Tylor’s scholarly output, though limited to four major books, profoundly shaped anthropology. His first work, Anahuac: Or Mexico and the Mexicans, Ancient and Modern (1861), chronicled his Mexican expedition with Henry Christy, blending travelogue with early anthropological observations on cultural differences and indigenous practices. While not a theoretical masterpiece, it showcased Tylor’s empirical approach and hinted at his later evolutionary framework, though it reflected Victorian ethnocentrism in its judgments of non-European cultures. Researches into the Early History of Mankind and the Development of Civilization (1865) established Tylor’s reputation, arguing that all human cultures form a single developmental history, with past and present societies interconnected through evolutionary progress. It introduced his comparative method, using global cultural data to trace human thought’s evolution. Primitive Culture: Researches into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Language, Art, and Custom (1871), his magnum opus, is a two-volume work that formalized his theories of cultural evolution, animism, and survivals. Its comprehensive analysis of mythology, religion, and customs, supported by extensive references, made it a cornerstone of anthropology, influencing scholars like James Frazer. Anthropology: An Introduction to the Study of Man and Civilization (1881), a more accessible text, summarized Tylor’s ideas for a broader audience, covering topics from material culture to social institutions. Additionally, his 1888 article, “On a Method of Investigating the Development of Institutions,” applied statistical analysis to marriage and descent patterns, showcasing his methodological innovation. Though Tylor intended to publish The Natural History of Religion based on his 1888 Gifford Lectures, it remained unpublished due to his declining health and waning relevance of his ideas. These works, marked by clarity and breadth, cemented Tylor’s legacy as anthropology’s founding theorist.

Critics

Tylor’s theories, while groundbreaking, faced significant criticism for their assumptions and limitations. His unilinear model of cultural evolution, assuming all societies progress through fixed stages, was criticized by later anthropologists like Franz Boas, who advocated historical particularism, arguing that each culture’s development is unique and context-specific. Boas and his students rejected Tylor’s view of “primitive” societies as living fossils, emphasizing cultural relativism over evolutionary hierarchies. Edward Evans-Pritchard, a 20th-century anthropologist, critiqued Tylor’s animism theory, arguing it oversimplified religious practices by reducing them to intellectual errors, ignoring their emotional and social roles. Critics like Martin Stringer noted inconsistencies in Tylor’s views on animism, particularly between his public dismissal of spiritualism and private curiosity, as revealed in his unpublished notes. Tylor’s armchair approach, relying on secondary data rather than fieldwork, drew criticism for its lack of empirical rigor, with later anthropologists like Bronisław Malinowski prioritizing immersive research. His ethnocentrism, evident in Anahuac’s condescending tone toward indigenous cultures, was seen as reflective of Victorian biases, associating “civilization” with Western society. Marxist and postcolonial scholars criticized Tylor’s framework for justifying colonial narratives by framing non-Western cultures as “savage,” thus supporting imperialist policies. His focus on intellectual aspects of religion, influenced by his Quaker agnosticism, undervalued ritual and emotional dimensions, as noted by Robert Ackerman. Despite these critiques, defenders like R.R. Marett praised Tylor’s methodological clarity and his role in establishing anthropology as a science, arguing that his work laid essential foundations despite its Victorian limitations. These debates highlight the tension between Tylor’s pioneering contributions and the evolving standards of anthropological inquiry.

Contemporary Relevance

Tylor’s ideas, though rooted in a Victorian context, continue to resonate in modern anthropology and beyond. His definition of culture as a “complex whole” remains a cornerstone, informing how anthropologists study the interplay of beliefs, customs, and institutions. While his unilinear evolutionism has been largely discarded, it laid the groundwork for discussions on cultural change, influencing fields like archaeology and cultural studies. The concept of survivals is still relevant in analyzing cultural persistence, such as superstitions or traditional practices in modern societies, and informs studies of cultural memory and heritage. Tylor’s animism theory, though oversimplified, sparked ongoing debates in religious studies about the origins and universality of spiritual beliefs, with scholars like Graham Harvey revisiting it to explore indigenous ontologies. His emphasis on the psychic unity of humankind, asserting equal intellectual potential across cultures, aligns with contemporary anthropology’s rejection of racial hierarchies and advocacy for cultural equity. In a globalized world, Tylor’s comparative method, despite its flaws, inspires cross-cultural research, particularly in understanding how global and local cultures interact. His work also informs discussions on decolonizing anthropology, as scholars critique his Eurocentric biases while building on his holistic approach to culture. In education, Tylor’s legacy as an Oxford professor underscores the importance of anthropology in fostering cross-cultural understanding, relevant to addressing issues like migration and cultural diversity. His ideas on progress and rationalism resonate in policy discussions on modernization and development, though tempered by critiques of universalist assumptions. By framing culture as a shared human endeavor, Tylor’s work continues to guide efforts to navigate cultural complexity in an interconnected world.

References

- Tylor, E.B. Primitive Culture: Researches into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Art, and Custom. 2 vols. John Murray, 1871.

- Tylor, E.B. Anahuac: Or Mexico and the Mexicans, Ancient and Modern. IndyPublish, 2007 (originally 1861).

- Tylor, E.B. Researches into the Early History of Mankind and the Development of Civilization. 3rd ed., John Murray, 1878.

- Tylor, E.B. Anthropology: An Introduction to the Study of Man and Civilization. Macmillan and Co., 1881

|

|

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|