Social Mobility

Index

Understanding Social Mobility

Social mobility is a core concept within the study of stratification in sociology. It refers to

the movement of individuals or groups within a stratified social hierarchy, which results in a

change in their social status, class position, or life chances. Unlike social stratication,

which denotes a relatively xed structure of inequality, social mobility is about the fluidity

within this structure. It shows how open or rigid a society is, and whether people can

improve or worsen their status through their own efforts or external forces. The concept

reflects the dynamic nature of modern society, where change in economic, political, or

cultural spheres creates new opportunities or obstacles for movement between different

strata.

In essence, social mobility encapsulates the possibilities individuals or social groups have for

upward or downward movement in terms of wealth, prestige, education, or occupation.

This concept became especially important in industrial societies, where traditional ascribed

statuses such as caste or kinship were expected to decline in importance, being replaced by

achieved statuses. Sociologists such as Pitirim Sorokin viewed mobility as the essence of

social openness and democratic promise. In his words, a completely mobile society would

be one in which “every individual would have an equal opportunity to rise or fall in the

social scale according to his own capacities.” However, real-world societies show significant

variations in the degree of mobility available, influenced by inherited privilege, institutional

structures, cultural norms, and political systems.

Open and Closed Systems of Social Mobility

One of the foundational distinctions in understanding social mobility is between open and

closed systems of stratification, which determine the extent to which mobility is possible. A

closed system of stratification restricts mobility to a great extent. These systems, such as

caste in traditional Indian society or feudal estates in medieval Europe, are rigid,

hierarchical, and often justified by religion or tradition. In closed systems, status is largely

ascribed at birth, and mobility is almost impossible. For example, in the Indian caste system,

individuals are born into a specific jati or varna, and their roles, occupations, and

interactions are largely predetermined. The system emphasizes ritual purity, endogamy, and

hereditary occupations, denying scope for individuals to alter their social position.

In contrast, an open system allows for more achieved status, meaning individuals can rise or

fall in the social hierarchy based on education, talent, effort, or luck. Capitalist democracies

are often considered examples of open systems, where people theoretically have the

opportunity to succeed regardless of their background. The concept of the “American

Dream” and the idea of meritocracy are often cited in this regard. However, even in such

systems, social mobility is not always easy. Class, race, gender, and region continue to

influence access to resources. Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of cultural capital explains how

even in open systems, the transmission of values, norms, and tastes through family and

education often reproduces inequality.

It is therefore more accurate to understand mobility as existing on a spectrum between

openness and closure, rather than as a binary. Even in relatively open systems, structural

impediments—such as unequal schooling, economic disparity, gender roles, or institutional

discrimination—can drastically affect one’s potential to move. Hence, sociologists often

analyze not just whether mobility is allowed in theory, but how it functions in practice.

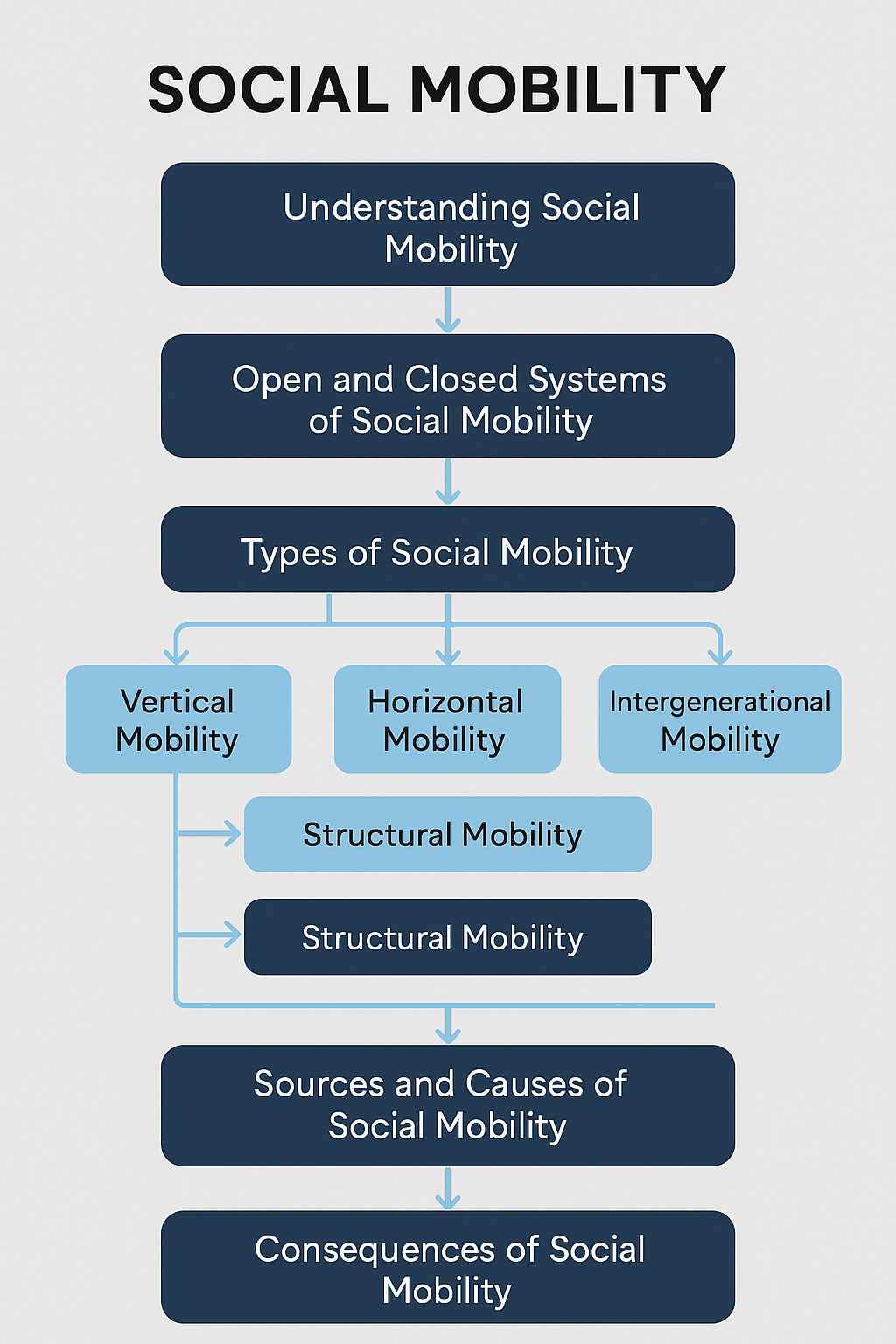

Types of Social Mobility

Social mobility can be classified into several different types based on direction, time, and context. These include vertical, horizontal, intergenerational, intragenerational, and structural mobility—each reflecting different dimensions of movement in a stratified society.

Vertical Mobility

Vertical mobility involves movement either upward or downward in the social hierarchy. When a person improves their social or economic status—such as a factory worker becoming a business owner—it constitutes upward vertical mobility. Conversely, downward mobility occurs when an individual loses status or income, such as a manager being demoted or falling into debt. Vertical mobility significantly affects class dynamics, prestige, and identity.

Horizontal Mobility

Horizontal mobility refers to a shift in social position without a change in status. For example, a government school teacher transferring to another government school of similar status represents horizontal mobility. Although it does not affect hierarchy directly, it may involve geographic, institutional, or occupational shifts, reflecting flexibility within a stratum.

Intergenerational Mobility

This occurs when individuals attain a social status different from that of their parents. A farmer’s child becoming a doctor or bureaucrat indicates intergenerational upward mobility. This form of mobility is particularly significant in measuring the openness of a society across generations. High intergenerational mobility suggests a break from hereditary stratification and greater merit-based advancement.

Intragenerational Mobility

This refers to mobility within the same generation, i.e., the social trajectory of an individual during their lifetime. A clerk becoming a CEO or an engineer losing their job and becoming a delivery worker are both examples. Intragenerational mobility provides insight into how careers evolve over a person’s life due to choices, opportunities, or misfortunes.

Structural Mobility

Structural mobility is driven not by individual attributes but by societal changes—such as industrialization, globalization, or policy shifts—that create or eliminate positions. For instance, the rise of the IT sector in India created space for the mobility of middle and lower-middle-class youth. Conversely, economic downturns or automation may lead to large-scale downward shifts.

Each type of mobility offers insights into how individuals navigate social structures, how societies evolve, and how inequality persists or changes. The intersection of caste, class, gender, and region further diversifies mobility experiences in complex ways.

Sources and Causes of Social Mobility

The phenomenon of social mobility is enabled or constrained by a number of factors, including individual capabilities, family background, access to education, cultural capital, political structures, and social policies.

Education

Perhaps the most influential and widely accepted source of social mobility in modern societies is education. It provides individuals with the skills, credentials, and knowledge required to access better occupations and higher income. In India, educational achievements have facilitated the upward mobility of several historically disadvantaged groups, such as Dalits and women. However, the quality of education and access remains highly unequal. Urban-rural divides, private-public disparities, and regional differences continue to limit educational outcomes for many.

Occupational Changes

Changes in occupation, either through job mobility or sectoral shifts, often lead to social mobility. For example, when rural youth migrate to cities and take up salaried jobs or start businesses, they often experience status enhancement. The emergence of new industries and the professionalization of services also open new avenues for economic advancement.

Urbanization and Migration

Urban centers oer anonymity, diversity, and access to varied employment options, all of which can support upward mobility. Rural-to-urban migration can liberate individuals from traditional social control systems like caste panchayats or kinship obligations. However, not all migrants succeed equally—many end up in informal and insecure jobs, indicating that urban migration alone is not a guarantee of mobility.

Social Movements and Political Representation

Movements like Dalit assertion, the OBC movement, women’s movements, and Adivasi rights activism have challenged hierarchical norms and enabled political, educational, and economic mobility. Reservation policies in India, although contentious, have acted as a major tool to promote the social mobility of disadvantaged groups. Representation in bureaucracy and politics has significantly improved the visibility and status of historically marginalized groups.

Economic Development and Globalization

Liberalization and globalization have created an aspirational consumer culture and new economic classes. Many from modest backgrounds have entered the middle class through private sector jobs, entrepreneurship, and digital platforms. However, economic volatility, jobless growth, and privatization also threaten to erode these gains, especially for those at the bottom of the economic ladder.

Consequences of Social Mobility

Social mobility can bring about transformative changes at both the individual and societal levels. It has significant psychological, cultural, political, and structural consequences.

Individual Level

For individuals, upward mobility often translates into increased self-esteem, economic security, and access to power and prestige. However, it may also lead to identity conicts and alienation. First-generation upwardly mobile individuals may experience discomfort in balancing their traditional cultural values with the expectations of their new social status. They may also face social isolation, as they become “outsiders” in both their old and new contexts. Downward mobility, on the other hand, can cause stress, anxiety, and a sense of failure.

Family and Kinship

Mobility affects family structures and relationships. The movement from joint to nuclear family settings is often a result of occupational and geographical mobility. Intergenerational tensions may arise when younger members reject traditional authority or caste boundaries. Women’s mobility may be viewed as a threat to patriarchal norms, leading to conflict and even violence.

Cultural and Symbolic Effects

Cultural shifts accompany mobility. Language, dress, tastes, and social behavior evolve as individuals enter new social milieus. However, symbolic distinctions persist, and Bourdieu’s notion of “distinction” reveals how elite groups use cultural markers to exclude others even in contexts of formal equality

Stratification System

At a macro level, widespread mobility may indicate a transition from a rigid stratification system to a uid one. However, mobility does not always imply reduced inequality. In fact, selective mobility may reinforce inequality if only certain groups gain access to new opportunities. The promise of mobility may be used to legitimize systemic inequalities, presenting success as purely a matter of individual effort, even when structural barriers persist.

Political and Social Stability

Social mobility contributes to democratization and social cohesion when it is inclusive. However, the denial of mobility or the experience of blocked mobility can result in frustration, resentment, and social unrest. In such scenarios, mobility—or the lack of it—becomes a politically charged issue.

Conclusion

Social mobility is not only a key sociological concept but a powerful force that shapes the aspirations, structures, and dynamics of society. It reveals the degree to which individuals and groups can overcome barriers and alter their life trajectories. In traditional societies, mobility was constrained by ascriptive systems like caste and feudalism, whereas modern societies promised merit-based advancement. However, the reality is more complex—mobility is often uneven, selective, and dependent on multiple social factors. In the Indian context, while legal reforms, economic development, and educational access have improved mobility, deeply entrenched hierarchies—especially of caste, gender, and region—continue to impede it. The task of sociology, therefore, is not just to measure mobility but to understand the structures that enable or constrain it. A just society must ensure that mobility is not just a dream for a few but a reality for all.

References

- Sorokin, Pitirim. Social and Cultural Mobility. New York: Free Press, 1959.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Harvard University Press, 1984

- Yogendra Singh. Modernization of Indian Tradition: A Systemic Study of Social Change. Thomson Press, 1973.

Individuals are recognized in society through the statuses they occupy and the roles they enact. The society as well as individuals is dynamic. Men are normally engaged in endless endeavor to enhance their statuses in society, move from lower position to higher position, secure superior job from an inferior one. For various reasons people of the higher status and position may be forced to come down to a lower status and position. Thus people in society continue to move up and down the status scale. This movement is called social mobility.

The study of social mobility is an important aspect of social stratification.Infact it is an inseparable aspect of social stratification system because the nature, form, range and degree of social mobility depends on the very nature of stratification system. Stratification system refers to the process of placing individuals in different layers or strata.

|

|

According to Wallace and Wallace social mobility is the movement of a person or persons from one social status to another.W.P Scott has defined sociology as the movement of an individual or group from one social class or social stratum to another.

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|