Home » Social Thinkers » Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes

Edmund Leach

Table of Contents

Introduction

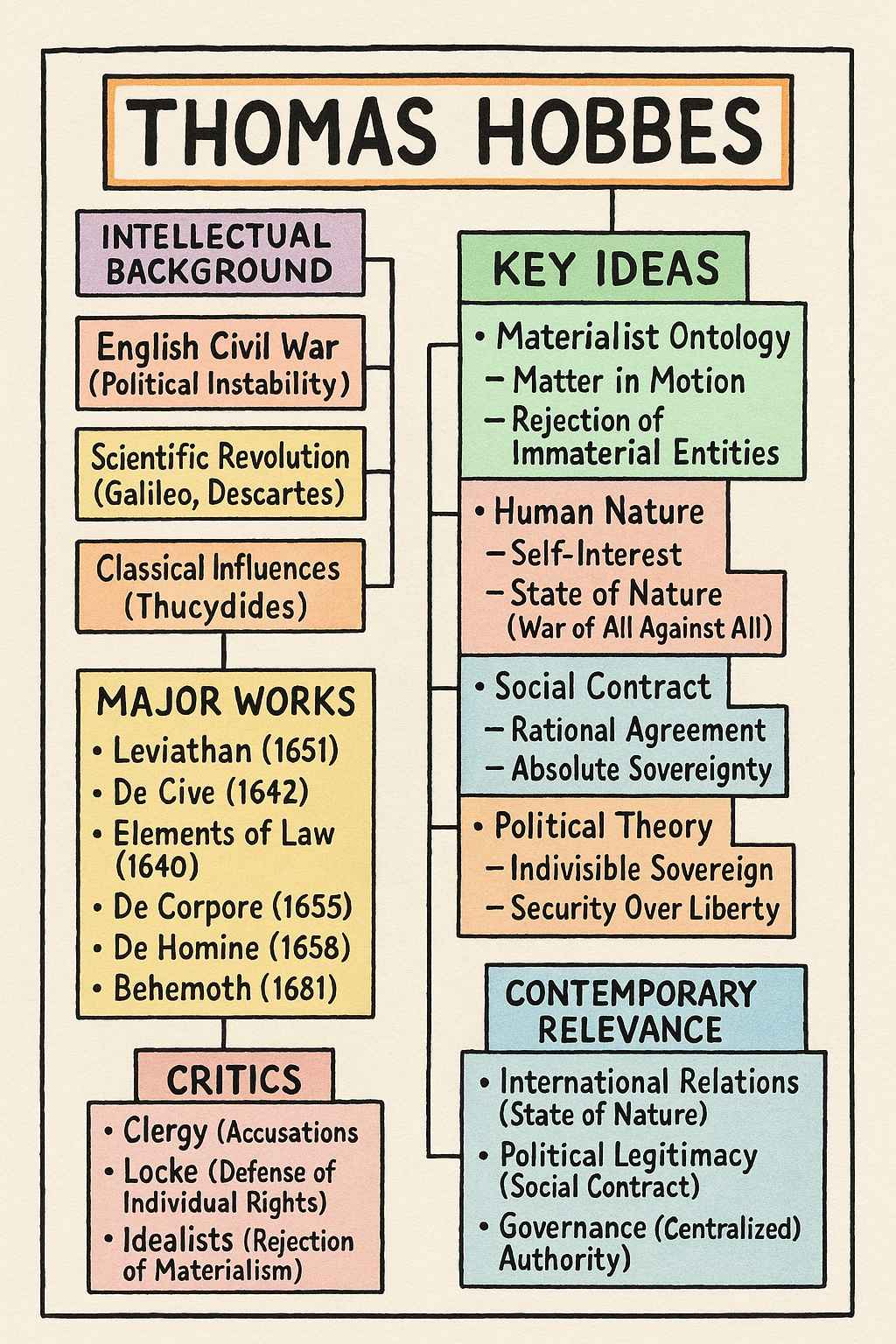

Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679), one of the most influential political philosophers in Western thought, is renowned for his foundational contributions to social contract theory and his materialist worldview. Born in Westport, England, during a time of political and religious upheaval, Hobbes’ early life was shaped by the English Civil War, the rise of Puritanism, and the instability of monarchical rule. Educated at Oxford University, Hobbes initially engaged with classical texts, translating Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War, which exposed him to the destructive potential of political factionalism. His intellectual development was further influenced by his travels across Europe, where he met key figures of the Scientific Revolution, including Galileo and Descartes, whose mechanistic views of the universe profoundly shaped his philosophy. Hobbes rejected the scholasticism of his time, which relied heavily on Aristotelian metaphysics, in favor of a materialist and empirical approach, emphasizing observable phenomena and human behavior. His role as a tutor to the aristocratic Cavendish family provided him access to intellectual circles and political debates, deepening his interest in governance and human nature. The turmoil of the English Civil War (1642–1651) reinforced his belief in the need for a strong, centralized authority to prevent chaos, a theme central to his philosophy. Hobbes’ interactions with the Royal Society and his engagement with mathematics and optics further grounded his mechanistic view of reality, where human actions, like physical objects, follow predictable laws. This intellectual background, blending classical learning, scientific rationalism, and political realism, positioned Hobbes to develop a philosophy that prioritized order, security, and rational governance.

Key Ideas and Concepts

Hobbes’ philosophy is anchored in his materialist ontology and his view of human nature as inherently self-interested and competitive. He argued that the universe consists solely of matter in motion, rejecting metaphysical entities like souls or immaterial spirits. This materialism extended to his anthropology, where he described humans as driven by appetites and aversions, seeking self-preservation above all. In his famous depiction of the “state of nature,” Hobbes envisioned a pre-social condition where individuals, motivated by fear and desire, engage in a “war of all against all,” rendering life “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” To escape this chaos, individuals enter a social contract, surrendering certain freedoms to a sovereign authority in exchange for security and order. This sovereign, whether a monarch or an assembly, holds absolute power to enforce laws and maintain peace, as any division of authority risks returning society to anarchy. Hobbes’ social contract theory marked a significant departure from divine-right theories of governance, grounding political legitimacy in rational agreement rather than divine mandate. His concept of sovereignty emphasized indivisibility and absoluteness, arguing that the sovereign’s authority must be unquestioned to prevent civil conflict. In epistemology, Hobbes was a nominalist, asserting that universal concepts like “justice” or “good” are mere names, not reflective of objective truths, aligning with his rejection of metaphysical absolutes. His ethical framework, rooted in self-preservation, viewed morality as a set of rational rules derived from the social contract to ensure mutual survival. Hobbes also explored human psychology, arguing that passions, particularly fear, drive political behavior, making a strong sovereign essential to channel these passions constructively. These ideas collectively underscore Hobbes’ commitment to stability through rational, centralized governance.

Major Works and Their Explanations

Hobbes’ philosophical contributions are primarily articulated in his written works, which span political theory, philosophy, and science. His most famous work, Leviathan (1651), is a comprehensive treatise on political philosophy, outlining his social contract theory, the state of nature, and the necessity of an absolute sovereign. Structured in four parts, Leviathan covers human nature, the formation of the commonwealth, the Christian commonwealth, and the “Kingdom of Darkness,” critiquing religious superstition. Written during the English Civil War, it reflects Hobbes’ urgency to propose a solution to political instability. De Cive (1642), or On the Citizen, is an earlier work that systematically explores the relationship between individuals, society, and the state, emphasizing the social contract and the role of the sovereign in maintaining order. It was intended as part of a trilogy on body, man, and citizen, though Leviathan later expanded on its themes. Elements of Law (1640), circulated in manuscript form, laid the groundwork for Hobbes’ political philosophy, introducing his mechanistic view of human behavior and the need for a unified sovereign. De Corpore (1655) and De Homine (1658) form part of his philosophical trilogy, addressing physics and human nature, respectively, and reflecting his materialist and scientific approach. Hobbes also wrote Behemoth (1681), a historical analysis of the English Civil War, attributing its causes to religious fanaticism and divided authority. His translation of Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War (1629) reveals his early interest in political conflict and human nature. These works, combining rigorous argumentation with practical concerns, established Hobbes as a pivotal figure in political and philosophical thought.

Critics

Hobbes’ ideas, particularly his advocacy for absolute sovereignty and his materialist philosophy, sparked significant controversy. Contemporary critics, including royalists and clergy, accused him of atheism due to his rejection of immaterial substances and his critique of religious authority in Leviathan. This led to his works being banned and burned in some circles. Royalist thinkers, while supportive of monarchy, disagreed with Hobbes’ secular justification of sovereignty, preferring divine-right arguments. Parliamentarians and republicans, on the other hand, opposed his absolutism, viewing it as a defense of tyranny. John Locke, a later social contract theorist, critiqued Hobbes for undermining individual rights, arguing that the social contract should preserve liberty rather than surrender it to an absolute sovereign. In the 20th century, scholars like Leo Strauss debated whether Hobbes’ philosophy was a genuine defense of order or a subtle critique of authoritarianism, given his emphasis on rational consent. Feminist critics have noted that Hobbes’ state of nature and social contract implicitly exclude women, reflecting the patriarchal assumptions of his time. His nominalism and rejection of metaphysical truths drew criticism from idealists and religious philosophers, who argued that his reduction of morality to self-interest undermined ethical absolutism. Despite these critiques, defenders like C.B. Macpherson have praised Hobbes for his realism and for laying the groundwork for modern political theory by emphasizing rational consent over divine or traditional authority. The controversies surrounding Hobbes highlight the radical nature of his ideas and their challenge to established norms.

Contemporary Relevance

Hobbes’ philosophy remains strikingly relevant in modern political, social, and philosophical discourse. His concept of the state of nature resonates in discussions of international relations, where the absence of a global sovereign mirrors Hobbes’ vision of anarchy, informing realist theories that prioritize state power and security. The social contract theory continues to shape debates on political legitimacy, influencing modern democratic theories and discussions about the balance between individual rights and state authority. Hobbes’ emphasis on fear and self-preservation finds echoes in contemporary analyses of political behavior, particularly in times of crisis, such as during pandemics or civil unrest, where strong governance is oen demanded. His materialist worldview aligns with modern scientific perspectives, particularly in cognitive science and psychology, where human behavior is increasingly understood through neurological and evolutionary lenses. In political philosophy, Hobbes’ advocacy for centralized authority raises questions about the role of government in addressing global challenges like climate change or terrorism, where coordinated action is essential. His critique of religious fanaticism in Behemoth remains relevant in analyzing the impact of ideological extremism on political stability. However, his absolutism is oen contrasted with liberal democratic values, prompting discussions about the limits of state power in surveillance, privacy, and civil liberties. Hobbes’ ideas on language and nominalism also influence contemporary philosophy of language and semiotics, particularly in debates about meaning and truth in a post-truth era. By addressing timeless questions about human nature, governance, and order, Hobbes’ philosophy continues to provide a framework for understanding modern political and social dynamics.

References

- Hobbes, Thomas. Leviathan. Edited by Richard Tuck, Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Hobbes, Thomas. De Cive. Translated by Richard Tuck and Michael Silverthorne, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Macpherson, C.B. The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism: Hobbes to Locke. Oxford University Press, 1962.

- Martinich, A.P. Hobbes: A Biography. Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Skinner, Quentin. Visions of Politics: Volume 3, Hobbes and Civil Science. Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Strauss, Leo. The Political Philosophy of Hobbes: Its Basis and Its Genesis. University of Chicago Press, 1952

|

|

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|