Home » Social Inequality and Exclusion

Social Inequality and Exclusion

Index

Introduction

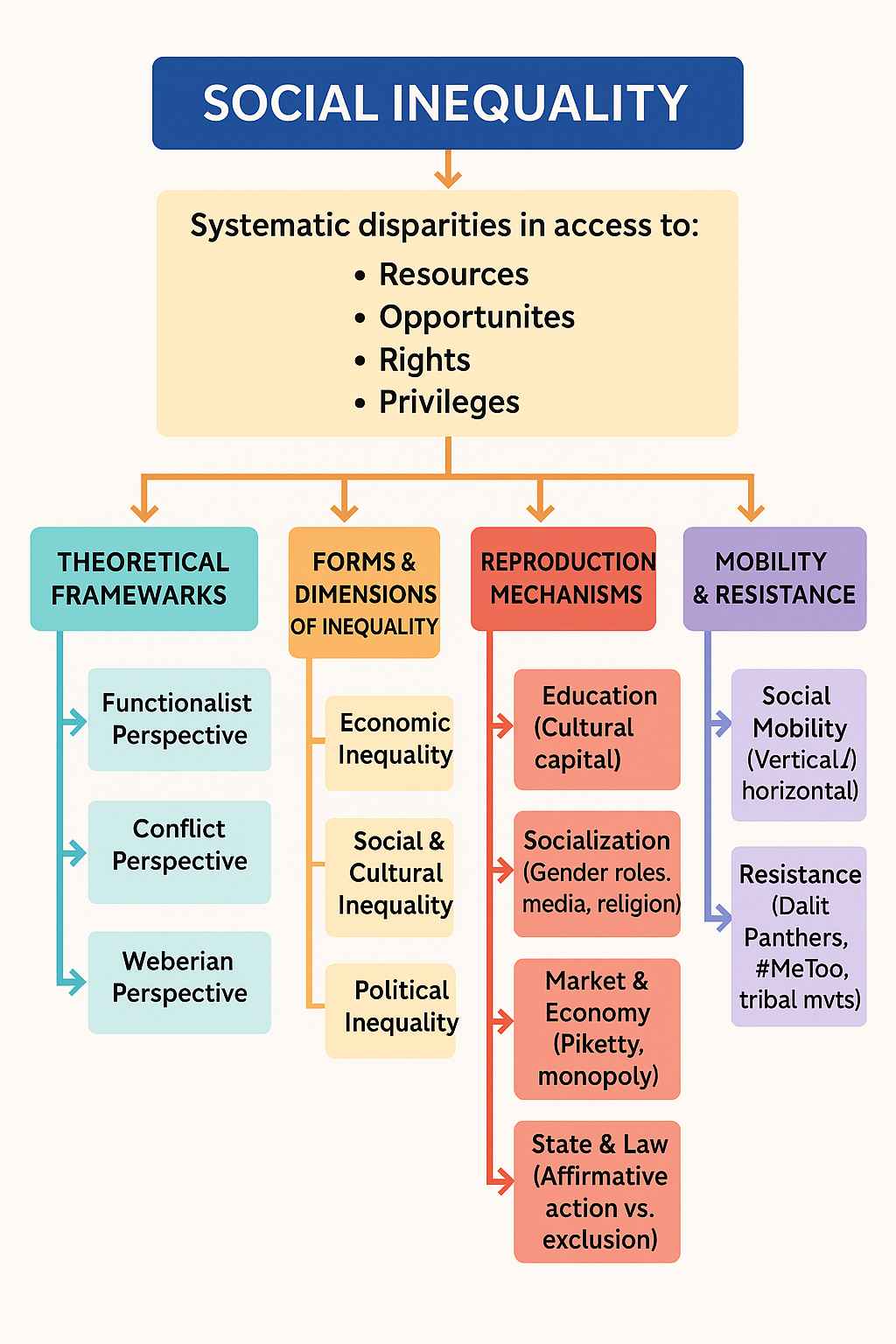

Social inequality refers to the systematic, institutionalized disparities in access to resources,

opportunities, rights, and privileges among different social groups. These disparities are not

random but are embedded in societal structures, manifesting across dimensions such as

class, caste, gender, race, ethnicity, religion, age, disability, and geography. Unlike individual

differences, social inequality is structural, perpetuated through historical processes, cultural

norms, and institutional practices, often enduring across generations. For sociologists,

inequality is a central lens for understanding social organization, as it shapes power

dynamics, social interactions, identities, and perceptions of justice and legitimacy.

In India, a society marked by deep diversity and historical hierarchies, social inequality takes

unique forms, such as caste-based exclusion, gender disparities, and regional imbalances.

Theoretical Frameworks for Understanding Social Inequality

A. Functionalist Perspective

Functionalist sociologists, notably Talcott Parsons and Kingsley Davis and Wilbert Moore, argue that social inequality is a necessary and functional aspect of society. The Davis-Moore thesis (1945) posits that certain roles—such as doctors, engineers, or administrators—are more critical to societal functioning due to their complexity or scarcity of skills. To incentivize qualified individuals to undertake these roles, society offers greater rewards, such as wealth, status, or power, resulting in structured inequality. Parsons extended this idea through his concept of role differentiation, suggesting that inequality reflects a merit-based allocation of roles within a consensual value system, ensuring social stability. For example, in India, the high status and income of IIT-educated engineers can be seen as a functional reward for their specialized skills. However, critics, particularly conflict theorists, argue that functionalism overlooks how power and privilege shape access to these roles, often justifying elite dominance.

Critique: The functionalist perspective is criticized for ignoring systemic barriers, such as caste or gender, that prevent equal access to opportunities, thus legitimizing existing hierarchies rather than questioning them.

B. Conflict Perspective

Rooted in Karl Marx’s historical materialism, the conflict perspective views social inequality

as the outcome of exploitation and class struggle in capitalist societies. Marx divided society

into two antagonistic classes: the bourgeoisie, who own the means of production (e.g.,

factories, land), and the proletariat, who sell their labor for wages. Inequality arises because

capitalists extract surplus value—the difference between the value produced by workers and

their wages—leading to wealth concentration. Beyond economics, Marx argued that the

bourgeoisie control the ideological superstructure (e.g., media, education, religion), which

legitimizes their dominance by portraying inequality as natural or inevitable.

Neo-Marxist thinkers like Antonio Gramsci and Louis Althusser rened this framework.

Gramsci’s concept of hegemony explains how ruling-class ideologies are internalized by the

oppressed, making inequality appear consensual. For instance, the glorication of corporate

success in Indian media may normalize wealth disparities. Althusser introduced Ideological

State Apparatuses (e.g., schools, courts), which reproduce class relations by shaping

individual beliefs and behaviors. These ideas highlight how inequality is sustained not just

through economic control but through cultural and ideological mechanisms.

Critique: While powerful, Marx’s economic determinism is critiqued for

underemphasizing non-economic factors like gender or caste, which Weber and feminist

theorists address.

C. Weberian Perspective

Max Weber oered a multidimensional analysis of inequality, moving beyond Marx’s focus

on class. Weber identified three distinct dimensions: class (economic position and

market-based life chances), status (social honor, prestige, or lifestyle), and party (political

power and infl uence). For example, in India, a Brahmin priest may lack wealth but enjoy

high status due to cultural reverence, while a wealthy Dalit entrepreneur may face social

stigma despite economic success. Weber’s framework highlights how economic, social, and

political inequalities intersect, allowing for complex identities and potential mobility across

dimensions.

Weber’s emphasis on status groups is particularly relevant in India, where caste and religion

shape social hierarchies beyond economic class. His concept of social closure—where groups

restrict access to resources or opportunities—explains practices like endogamy in caste

systems or elite networks in corporate India.

Critique: While Weber’s approach adds nuance, it can be complex to apply empirically, as

class, status, and power often overlap in practice

D. Feminist Theories

Feminist sociologists highlight patriarchy—a system of male dominance—as a key driver of

gender-based inequality. Sylvia Walby’s theory of patriarchy identifies six

structures—household production, paid work, state, culture, sexuality, and violence—that

interlock to subordinate women. For instance, women’s unpaid domestic labor in India

sustains economic systems while limiting their workforce participation. Judith Butler’s

concept of gender performativity challenges the notion of xed gender roles, arguing that

gender is a socially constructed performance shaped by repetitive norms, such as

expectations of femininity in Indian households.

Intersectional feminists like Kimberlé Crenshaw emphasize how gender intersects with race,

class, and caste to create layered inequalities. For example, Dalit women in India face

compounded discrimination, experiencing caste-based exclusion, gender violence, and

economic marginalization. Feminist perspectives broaden the inequality discourse to

include issues like unpaid care work, bodily autonomy, and cultural violence, which are

often sidelined in class-centric analyses.

E. Postmodern and Cultural Perspectives

Pierre Bourdieu’s concepts of cultural capital (knowledge, skills, tastes), social capital

(networks), and habitus (internalized dispositions) explain how non-economic resources

perpetuate inequality. In India, elite schools impart cultural capital—such as English

uency or Westernized manners—that aligns with institutional expectations, giving

upper-class children an edge in education and employment. Bourdieu’s framework reveals

how inequality is reproduced subtly through socialization and institutional biases.

Michel Foucault’s analysis of power-knowledge and discourses highlights how institutions

like schools, hospitals, or prisons shape subjectivities through disciplinary practices. For

example, standardized curricula in India may marginalize indigenous knowledge,

reinforcing cultural hierarchies. These perspectives underscore the symbolic and cultural

dimensions of inequality, complementing economic analyses

Forms and Dimensions of Social Inequality

Social inequality manifests in interconnected forms, each with distinct characteristics:

A. Economic Inequality

Economic inequality, measured by income, wealth, and employment access, is a global and Indian challenge. The Gini coecient, poverty indices, and unemployment rates reveal stark disparities. Oxfam’s 2023 report noted that the top 1% in India own over 40% of the nation’s wealth, while millions live below the poverty line. Economic inequality limits access to healthcare, education, and housing, perpetuating cycles of deprivation.

B. Social and Cultural Inequality

Social hierarchies based on caste, race, ethnicity, or religion shape access to resources and opportunities. In India, caste governs marriage, housing, and even access to public spaces like temples or wells. Cultural practices, such as language preferences (e.g., Hindi dominance in North India), and spatial segregation (e.g., urban slums) reinforce these divisions.

C. Political Inequality

Unequal access to political power and representation marginalizes groups like Dalits, tribals, and minorities. In India, reservation policies aim to ensure representation, but systemic barriers—such as elite capture of political processes—limit their impact. For instance, women hold only 14% of Lok Sabha seats despite comprising half the population.

D. Gender Inequality

Gender disparities manifest in wage gaps (women earn 20–30% less than men in India, per ILO), political underrepresentation, and violence. Patriarchal norms, such as son preference or restrictions on women’s mobility, perpetuate these inequalities. The skewed sex ratio (940 females per 1000 males in 2020) reflects systemic gender bias.

E. Spatial and Regional Inequality

Spatial disparities, such as urban-rural divides or inter-state differences (e.g., Kerala’s high HDI vs. Bihar’s low HDI), exacerbate inequality. The digital divide, amplified during COVID-19, left rural and low-income students without access to online education, deepening educational disparities.

Mechanisms of Inequality Reproduction

Inequality is sustained through interconnected social, economic, and institutional mechanisms:

A. Education

Bourdieu’s concept of cultural capital explains how education systems favor elite norms. In India, private English-medium schools cater to upper classes, while underfunded public schools serve marginalized groups, perpetuating class and caste divides. The hidden curriculum—implicit norms like discipline or language prociency—further disadvantages students from non-elite backgrounds.

B. Socialization

Families, media, and religion socialize individuals into accepting inequality. For example, gender roles are reinforced through childhood practices (e.g., girls assigned domestic chores) and media portrayals of traditional masculinity or femininity. Religious teachings may also legitimize caste hierarchies, as seen in historical interpretations of varna.

C. Market and Economy

Capitalist economies naturally concentrate wealth, as Thomas Piketty demonstrates in Capital in the 21st Century. He argues that capital returns (e.g., investments) outpace economic growth, leading to wealth accumulation among elites. In India, corporate monopolies and informal labor markets exacerbate economic disparities.

D. State and Law

State policies can either challenge or reinforce inequality. Affirmative action, like reservations, seeks inclusion, but exclusionary laws (e.g., anti-conversion bills) or poor implementation (e.g., corruption in welfare schemes) can entrench disparities. For instance, delays in scholarship disbursements for SC/ST students limit their educational access.

Social Mobility and Resistance

Despite structural constraints, social mobility and resistance provide avenues for change:

Mobility: Vertical mobility (upward/downward movement) and horizontal mobility (movement within the same social level) are possible but constrained by access to education, healthcare, and networks. For example, a Dalit professional may achieve economic mobility but face social exclusion.

Resistance: Movements like the Dalit Panthers, women’s rights campaigns, tribal protests, and digital activism challenge systemic inequalities. For instance, #MeToo in India amplified voices against gender-based violence. However, structural barriers, such as repression of protests or lack of resources, limit their transformative potential.

References

- Davis, K., & Moore, W. E. (1945). Some Principles of Stratication. American Sociological Review, 10(2), 242–249.

- Marx, K. (1867). Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. (Original work published in German; widely referenced in conict theory discussions).

- Weber, M. (1922). Economy and Society. (Original work published in German; edited and translated by G. Roth & C. Wittich, 1978). Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Walby, S. (1990). Theorizing Patriarchy. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Butler, J. (1990). Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge.

In every society some people have a greater share of valued resources-money, property, education, health and power than others. These social resources can be divided into three forms of capital-economic capital in the form of material assets and income; cultural capital such as educational qualifications and status; and social capital in the form of networks of contacts and social associations. Often these three forms of capital overlap and one can be converted into the other.

|

|

For example a person from a well-off family can afford expensive higher education and so can acquire cultural or educational capital. Patterns of unequal access to social resources are commonly called social inequality. Social inequality reflects innate differences between individuals for example their varying abilities and efforts. Someone may be endowed with exceptional intelligence or talent or may have worked very hard to achieve their wealth and status. However by and large social inequality is not the outcome of innate or natural differences between people but is produced by the society in which they live.

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|