Home » Social Thinkers » Sorokin

|

|

Sorokin

Index

|

|

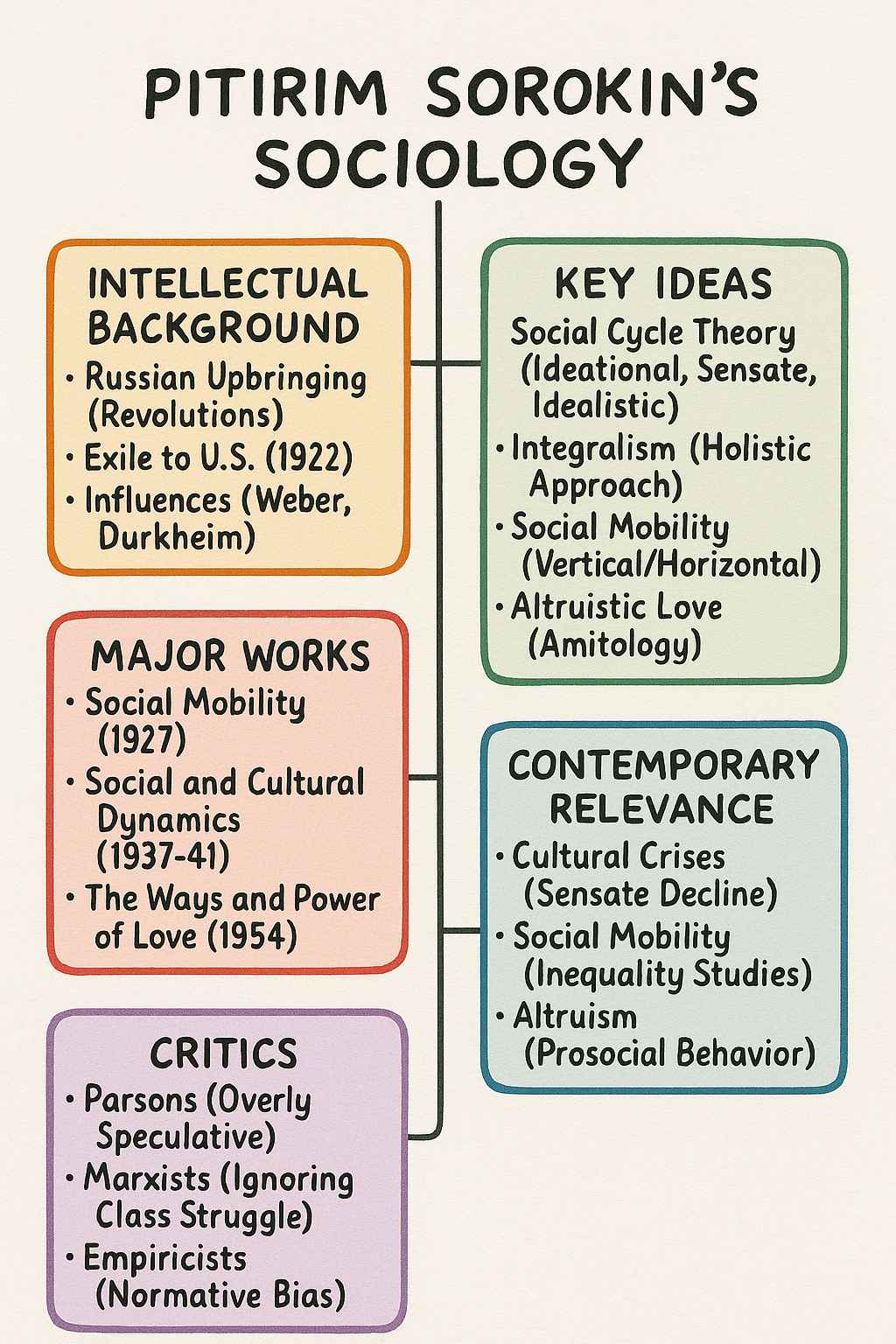

Introduction and Intellectual Background

Pitirim Alexandrovich Sorokin (1889–1968), a Russian-American sociologist and social philosopher, stands as one of the most original and controversial figures in 20th-century sociology, renowned for his contributions to social cycle theory, social mobility, and the sociology of altruism. Born on January 21, 1889, in Turya, a remote village in Russia’s Vologda Governorate (now Komi Republic), Sorokin emerged from humble beginnings as the son of a Russian artisan father, Alexander Prokopievich, and a Komi peasant mother, Pelageya Vasilievna. Orphaned at age ten aer his mother’s death, Sorokin and his older brother Vasily worked as itinerant crasmen, exposing him to the social realities of rural Russia. Despite these challenges, his intellectual prowess earned him scholarships, leading to studies at the Psycho-Neurological Institute and the University of St. Petersburg, where he earned a doctorate in sociology. Sorokin’s early intellectual formation was shaped by Russia’s turbulent political landscape, including the 1905 and 1917 revolutions. A committed anti-tsarist and later anti-Bolshevik, he served as secretary to Alexander Kerensky in the 1917 Provisional Government and was imprisoned multiple times, facing a death sentence under Lenin before being exiled in 1922 with help from figures like Thomas Masaryk. Sorokin’s Russian experiences, combined with influences from philosophers like Vladimir Soloviev and sociologists like Max Weber, Émile Durkheim, and Auguste Comte, fostered his interest in the interplay of culture, values, and social change. Aer brief stays in Czechoslovakia, he emigrated to the United States in 1923, joining the University of Minnesota (1924–1930) before founding and chairing Harvard University’s sociology department (1930–1944). His interdisciplinary background, blending sociology, philosophy, and history, and his firsthand experience of revolution and exile, positioned Sorokin to develop a distinctive sociological framework that emphasized cultural dynamics, social mobility, and the transformative power of altruism. His later years, marked by a focus on creative altruism and the establishment of the Harvard Center for Research in Creative Altruism, reflected his commitment to sociology as a tool for social reconstruction, leaving a lasting legacy despite periods of academic marginalization.

Key Ideas and Concepts

Sorokin’s sociological contributions revolve around his ocial cycle theory,

integralism, social mobility, and altruistic love, which collectively address

the dynamics of cultural and social change. His social cycle theory, most fully

articulated in Social and Cultural Dynamics, posits that civilizations oscillate

between three cultural supersystems: ideational, sensate, and idealistic.

Ideational cultures prioritize spiritual values, faith, and transcendental truths,

oen seen in religious or ascetic societies, such as medieval Europe. Sensate

cultures, dominant in modern Western civilization since the Renaissance,

emphasize empirical knowledge, sensory experiences, and material progress,

valuing science and individualism. Idealistic cultures represent a synthesis,

balancing spiritual and material values, as seen in periods like the High

Middle Ages. Sorokin argued that Western society, in its sensate phase, was

approaching a crisis of decadence due to its overemphasis on materialism,

predicting a shi toward a new ideational or idealistic era. Each supersystem

shapes human needs, goals, and methods of satisfaction, influencing art, law,

ethics, and social relationships. This cyclical view, inspired by Oswald

Spengler’s The Decline of the West and Victor Cousin’s philosophical cycles,

rejected linear progress narratives, emphasizing recurring patterns driven by

shis in cultural mentality.

Sorokin’s integralism is a holistic ontology and epistemology that views

personality, society, and culture as interdependent, constantly evolving

systems. Unlike reductionist approaches, integralism insists that sociocultural

phenomena must be studied dynamically, across micro, meso, and macro

levels, integrating empirical, rational, and spiritual forms of knowledge. This

framework underpinned his critique of positivism and his advocacy for a

sociology that serves humanity by addressing social issues holistically. Social

mobility, a key focus of Sorokin’s early work, examines how individuals and

groups move across economic, political, and occupational strata. In Social

Mobility (1927), he analyzed vertical (upward/downward) and horizontal

mobility, identifying structural factors like education and economic systems

that facilitate or hinder movement. Sorokin viewed mobility as a universal

feature of societies but noted its varying rates and dysfunctional effects, such

as social disorganization, when excessive.

In his later years, Sorokin pioneered the sociology of altruistic love, proposing

“creative altruistic love” as a transformative force for social reconstruction. In

works like The Ways and Power of Love (1954), he argued that altruism, rooted in

spiritual and moral values, could counter the destructive tendencies of sensate

cultures, such as war and materialism. He envisioned a new science,

amitology, to study and promote altruistic behaviors, emphasizing their role

in fostering social cohesion. Sorokin’s focus on altruism reflected his belief

that sociology should not only analyze but also improve society, a vision

shaped by his experiences of violence and displacement. His concepts,

grounded in empirical data and historical analysis, offered a dynamic

framework for understanding cultural shis and social structures, challenging

the materialist biases of his time.

Major Works

Sorokin’s extensive oeuvre reflects his evolution from a revolutionary

intellectual to a global sociologist concerned with cultural dynamics and

human betterment. Social Mobility (1927) was his first major work in the

United States, establishing him as a leading theorist of social stratification.

The book analyzed the mechanisms and consequences of mobility, using

historical and statistical data to show how social structures shape

opportunities for movement. It introduced concepts like vertical and

horizontal mobility, influencing later stratification research. Social and Cultural

Dynamics (1937–1941), a four-volume magnum opus, is Sorokin’s most

ambitious work, presenting his social cycle theory. Based on extensive

historical and statistical analyses of art, law, ethics, and social institutions

from Greco-Roman times to the 20th century, it argued that cultural

supersystems drive societal change. The work’s quantitative approach,

including 100,000 index cards of data, was groundbreaking, though its dense

style limited its immediate impact.

The Crisis of Our Age (1941), a condensed version of Social and Cultural

Dynamics, popularized Sorokin’s diagnosis of Western civilization’s sensate

decline, predicting a transition to a more spiritual era. It appealed to a broader

audience, emphasizing the moral and cultural crises of modernity. Society,

Culture, and Personality (1947) synthesized his integralist approach, offering a

comprehensive framework for studying the interplay of individual, social, and

cultural systems. It emphasized the need for interdisciplinary methods to

understand complex social phenomena. The Ways and Power of Love (1954)

marked Sorokin’s shi to altruism, exploring how love and cooperation could

transform societies. Drawing on religious, philosophical, and scientific

traditions, it proposed amitology as a new field to study altruistic behaviors,

supported by case studies of figures like Gandhi and Jesus. Sociological Theories

of Today (1966) critiqued contemporary sociological trends, defending

integralism against positivism and advocating for a values-driven sociology.

These works, combining rigorous analysis with normative goals, cemented

Sorokin’s legacy as a visionary sociologist, though his focus on spiritual and

altruistic themes oen distanced him from mainstream academia.

Critics

Sorokin’s work, while innovative, faced significant criticism for its

methodological approaches, ideological implications, and perceived idealism.

Positivist sociologists, such as Talcott Parsons, his Harvard colleague,

criticized Social and Cultural Dynamics for its speculative nature, arguing that

its reliance on historical patterns lacked the empirical precision of

structural-functionalism. Parsons, who succeeded Sorokin as Harvard’s

sociology chair, viewed his cyclical theory as overly deterministic, ignoring

individual agency and specific social structures. Marxist scholars, like Herbert

Marcuse, dismissed Sorokin’s rejection of linear progress and his emphasis on

cultural supersystems as conservative, accusing him of downplaying class

struggle and economic determinism. They saw his integralism as diluting

revolutionary potential by focusing on spiritual and cultural factors.

Sorokin’s later focus on altruism and amitology drew skepticism from

empiricists who questioned the scientific validity of studying “love” as a

sociological phenomenon. Critics like Robert K. Merton argued that Sorokin’s

normative vision—advocating for a new altruistic era—compromised his

objectivity, blending sociology with moral philosophy. His broad historical

generalizations in Social and Cultural Dynamics were challenged by historians

like Arnold Toynbee, who criticized the lack of nuanced case studies and the

oversimplification of complex civilizations. Sorokin’s Russian background and

anti-Bolshevik stance also fueled accusations of bias, with Soviet scholars

labeling him a reactionary for his critiques of Marxist materialism. His

strained relationship with Harvard’s sociology department, particularly with

Parsons, led to his marginalization, as his holistic, value-driven approach

clashed with the rising tide of specialized, empirical sociology.

Sorokin’s personal style—described as combative and messianic—also

alienated peers. His public disputes with Parsons and his tendency to dismiss

rival theories as “narrow” contributed to his isolation. However, defenders like

Robert Bierstedt and Barry V. Johnston argue that Sorokin’s interdisciplinary

vision was ahead of its time, anticipating later holistic approaches in

sociology. They contend that his cyclical theory, while ambitious, provided a

valuable framework for understanding long-term cultural shis, and his focus

on altruism addressed human needs neglected by materialist paradigms.

Despite controversies, Sorokin’s influence persisted, particularly in social

mobility studies and cultural sociology, where his ideas continue to inspire

critical reflection.

Contemporary Relevance

Sorokin’s ideas remain highly relevant in addressing contemporary social,

cultural, and global challenges. His social cycle theory offers a framework for

understanding the crises of late modernity, such as environmental

degradation, political polarization, and cultural fragmentation. The decline of

sensate culture, with its emphasis on materialism and individualism, resonates

in debates about consumerism, mental health crises, and the erosion of

communal values. For instance, the rise of mindfulness movements and

spiritual revivals can be seen as signs of a shi toward an ideational or

idealistic phase, as Sorokin predicted. His cyclical perspective challenges

linear progress narratives, informing discussions of sustainability and the

limits of technological solutions to social problems.

The concept of social mobility remains central to sociology, with Sorokin’s

work informing studies of inequality, education, and economic opportunity. In

an era of growing wealth disparities, his insights into the structural barriers to

mobility—such as access to education and social networks—are critical for

policymakers addressing issues like income inequality and social inclusion.

His integralism aligns with contemporary interdisciplinary approaches, such

as those in cultural sociology and global studies, which seek to integrate

economic, cultural, and psychological perspectives. For example, Pierre

Bourdieu’s work on cultural capital and habitus echoes Sorokin’s emphasis on

the interplay of individual and social systems, though with a more critical lens

on power dynamics.

Sorokin’s sociology of altruistic love is particularly relevant in addressing

global challenges like climate change, migration, and social conflict. His call

for “creative altruism” resonates with movements promoting collective action,

such as grassroots activism and global humanitarian efforts. The Harvard

Center for Research in Creative Altruism’s legacy continues in studies of

prosocial behavior, with applications in psychology, organizational theory, and

conflict resolution. Sorokin’s emphasis on values-driven sociology inspires

efforts to foster empathy and cooperation in polarized societies, as seen in

initiatives promoting dialogue across political divides. His work also informs

critiques of hyper-individualism, offering a vision of social reconstruction

rooted in shared moral commitments.

In public discourse, Sorokin’s ideas have been cited to highlight the societal

importance of stable institutions. For example, former U.S. Vice President

Mike Pence referenced Sorokin’s findings on family stability in a 2006 speech

defending the Marriage Protection Amendment, underscoring the enduring

relevance of his insights on social cohesion. While Sorokin’s spiritual and

altruistic focus remains marginal in mainstream sociology, it anticipates the

growing interest in positive sociology and well-being studies, as seen in works

by scholars like Martin Seligman. By challenging materialist paradigms and

advocating for a values-driven approach, Sorokin’s legacy offers tools for

navigating the cultural and social complexities of the 21st century, from

globalization to ethical governance.

References

- Sorokin, P. A. (1927). Social Mobility. New York: Harper & Brothers.

- Sorokin, P. A. (1937–1941). Social and Cultural Dynamics (Vols. 1–4). New York: American Book Company.

- Sorokin, P. A. (1941). The Crisis of Our Age. New York: E. P. Dutton.

- Sorokin, P. A. (1947). Society, Culture, and Personality: Their Structure and Dynamics. New York: Harper & Brothers

- Sorokin, P. A. (1954). The Ways and Power of Love: Types, Factors, and Techniques of Moral Transformation. Boston: Beacon Press

- Sorokin, P. A. (1966). Sociological Theories of Today. New York: Harper & Row.

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|