Home » Social Thinkers » Plato

Plato

Index

Introduction

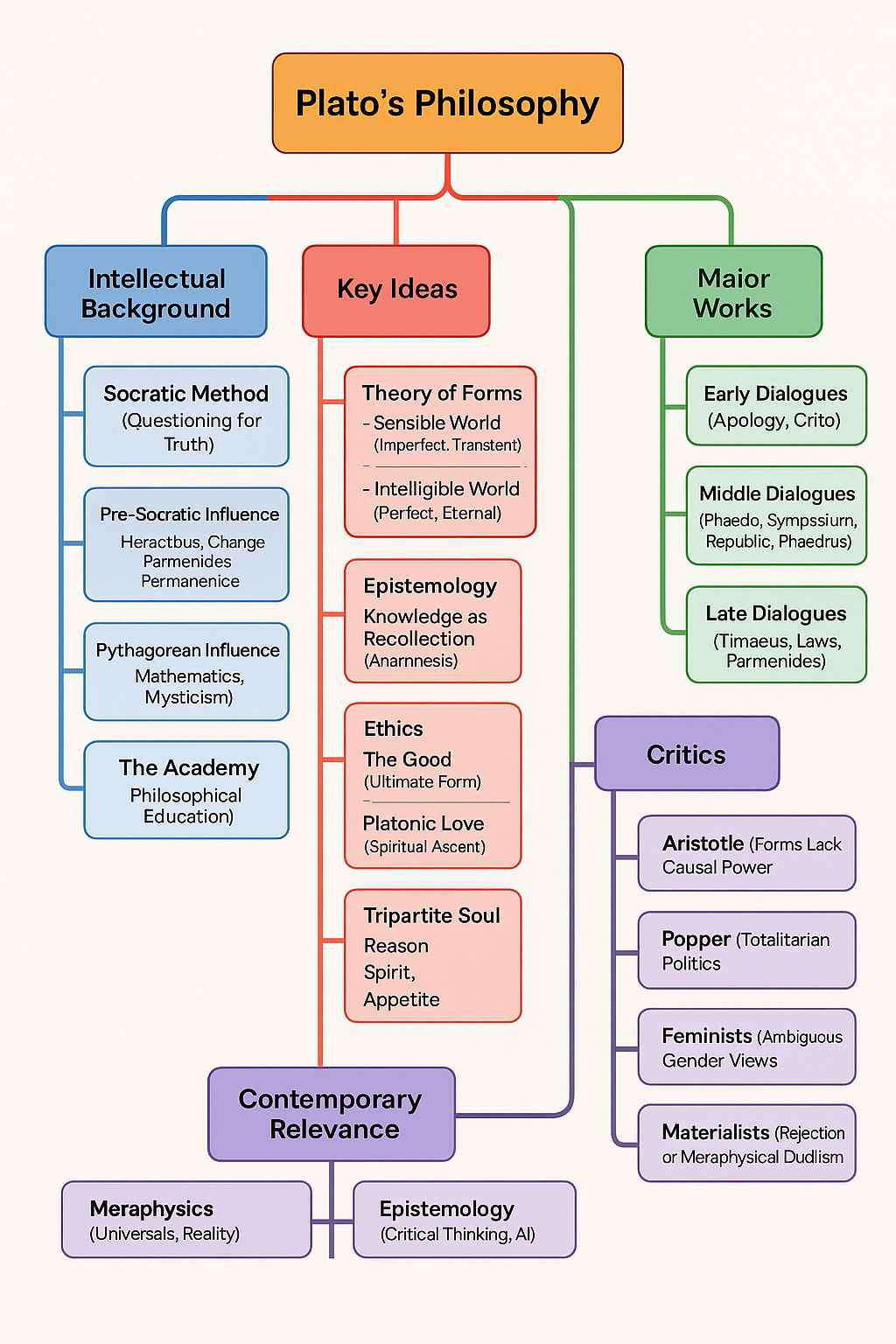

Plato (427–347 BCE), one of the most influential philosophers in Western thought, laid the foundation for much of philosophy, political theory, and epistemology. Born in Athens during a period of political turmoil, Plato, originally named Aristocles, was part of an aristocratic family with deep ties to Athenian politics. His early life was shaped by the Peloponnesian War, the decline of Athenian democracy, and the execution of his mentor, Socrates, in 399 BCE, which profoundly impacted his distrust of democratic governance. Plato’s intellectual journey began under the tutelage of Socrates, whose dialectical method of questioning to uncover truth became central to Plato’s philosophy. This Socratic influence, combined with his exposure to pre-Socratic thinkers like Heraclitus, who emphasized change, and Parmenides, who argued for the permanence of reality, shaped Plato’s metaphysical inquiries. Additionally, his travels to Sicily and interactions with Pythagorean philosophers introduced him to mathematical and mystical ideas, which influenced his theory of Forms. Plato’s establishment of the Academy in Athens, one of the earliest institutions of higher learning, marked a turning point in systematizing philosophical education. The Academy attracted thinkers like Aristotle, cementing Plato’s legacy as a teacher and philosopher. His intellectual background, rooted in a synthesis of Socratic ethics, pre-Socratic metaphysics, and Pythagorean mysticism, set the stage for his exploration of reality, knowledge, and governance, making him a pivotal figure in Western philosophy.

Key Ideas and Concepts

Plato’s philosophy revolves around several enduring concepts, with the Theory of Forms being the cornerstone. He proposed that the physical world is a shadow of a higher, eternal realm of perfect, immutable Forms or Ideas—archetypes of objects and qualities like beauty, justice, or goodness. For Plato, true knowledge is not derived from sensory experience, which is deceptive and transient, but from understanding these eternal Forms through reason and intellect. This metaphysical dualism distinguishes between the sensible world (of appearances) and the intelligible world (of Forms). His epistemology, closely tied to this, posits that knowledge is recollection (anamnesis), as the soul, which preexists in the realm of Forms, recalls truths upon encountering their imperfect copies in the physical world. This idea is vividly illustrated in his allegory of the cave, where prisoners, chained in a dark cave, mistake shadows for reality until one escapes to discover the outside world, symbolizing the philosopher’s ascent to knowledge. Plato’s ethical framework emphasizes the pursuit of the Good, which he considers the ultimate Form, guiding moral and political life. In politics, Plato advocated for a philosopher-king, an enlightened ruler who governs with wisdom and justice, as outlined in his ideal state. His theory of the tripartite soul—comprising reason, spirit, and appetite—parallels his ideal state’s structure (rulers, guardians, and producers), emphasizing harmony through rational governance. Plato’s ideas on love, particularly in the Symposium, explore the concept of Platonic love, a spiritual ascent from physical desire to the contemplation of divine beauty. His skepticism of art and poetry, as seen in his critique of mimesis (imitation), stems from their potential to distort truth by appealing to emotions rather than reason. These concepts collectively underscore Plato’s belief in a rational, ordered cosmos accessible through philosophical inquiry.

Major Works and Their Explanations

Plato’s philosophical contributions are primarily preserved in his dialogues, written in a dramatic form that showcases Socratic questioning. His works are typically categorized into early, middle, and late periods, reflecting shis in style and focus. Among his early dialogues, Apology presents Socrates’ defense during his trial, emphasizing his commitment to truth over conformity. Crito explores the tension between individual morality and civic duty, as Socrates refuses to escape execution to uphold justice. The middle dialogues, where Plato develops his distinctive philosophy, include Phaedo, which discusses the immortality of the soul and the Theory of Forms, using Socrates’ final hours as a backdrop. Symposium examines love through a series of speeches, culminating in Socrates’ account of love as a ladder to the divine. The Republic, Plato’s magnum opus, is a comprehensive exploration of justice, the ideal state, and the philosopher’s role. It introduces the allegory of the cave, the tripartite soul, and the philosopher-king, blending metaphysics, ethics, and politics. In Phaedrus, Plato delves into rhetoric, love, and the nature of the soul, using vivid imagery like the chariot allegory to depict the soul’s struggle for balance. His late dialogues, such as Timaeus, offer a cosmological account of the universe’s creation, blending myth and science, while Laws proposes a more practical, less idealistic political system governed by laws rather than philosopher-kings. Parmenides engages with critiques of the Theory of Forms, showcasing Plato’s willingness to question his own ideas. Written in a conversational style, these dialogues use characters and settings to explore complex ideas, making them both philosophical treatises and literary masterpieces.

Critics and Controversies

Plato’s philosophy, while groundbreaking, has faced significant criticism. His Theory of Forms, though influential, has been challenged for its abstract nature. Aristotle, Plato’s student, argued that Forms cannot exist independently of physical objects, as they lack causal power in the material world. This critique laid the groundwork for Aristotle’s more empirical approach. Modern philosophers, like Karl Popper, criticized Plato’s political ideas, particularly in The Republic, for promoting totalitarianism. Popper viewed the philosopher-king and the rigid class structure as anti-democratic, accusing Plato of prioritizing order over individual freedom. Feminist scholars have also critiqued Plato for his ambiguous stance on gender. While The Republic suggests women could be guardians, Plato’s portrayal of women in other dialogues oen reflects Athenian patriarchal norms. His distrust of art and poetry, articulated in The Republic, has drawn ire from artists and literary scholars who argue that his dismissal of mimesis undervalues creativity’s role in human experience. Additionally, Plato’s reliance on the Socratic method has been seen as dogmatic by some, as it assumes the possibility of absolute truth, which skeptics and postmodernists reject. His metaphysical dualism has been criticized by materialists and empiricists, who argue that knowledge derives from sensory experience, not an abstract realm. Despite these critiques, Plato’s defenders highlight his role in shaping philosophical inquiry, arguing that his idealism encourages critical reflection on reality and ethics. The debates surrounding his work underscore its complexity and enduring relevance.

Contemporary Relevance

Plato’s ideas remain profoundly relevant in modern philosophy, politics, and culture. His Theory of Forms influences contemporary metaphysics, particularly in debates about universals and the nature of reality. In epistemology, his emphasis on reason over sensory perception resonates in discussions about scientific knowledge and artificial intelligence, where distinguishing truth from data is critical. The allegory of the cave is frequently invoked in analyses of media, propaganda, and education, illustrating how perceptions can be manipulated and the importance of critical thinking. Plato’s political philosophy, particularly the concept of the philosopher-king, informs discussions on leadership and governance, raising questions about whether expertise should trump populism. His ideal state, though criticized, prompts reflection on balancing individual liberty with societal order, a tension evident in modern democratic debates. In ethics, Platonic love continues to shape discussions on relationships, emphasizing intellectual and spiritual connections over mere physical attraction. His tripartite soul finds parallels in psychology, particularly in theories of personality and motivation. Plato’s critique of art and mimesis resonates in debates about media ethics, fake news, and the impact of fiction on public perception. The Academy’s legacy as a model for higher education underscores the value of philosophical inquiry in fostering critical thought. In technology, Plato’s ideas about ideal forms parallel discussions on idealized models in AI and virtual reality. His dialogues, with their emphasis on questioning and dialogue, inspire modern pedagogical approaches that prioritize discussion over rote learning. By addressing timeless questions about truth, justice, and the good life, Plato’s philosophy continues to challenge and guide contemporary thought.

References

- Annas, Julia. Plato: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Cooper, John M., ed. Plato: Complete Works. Hackett Publishing, 1997

- Kraut, Richard. The Cambridge Companion to Plato. Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- Popper, Karl. The Open Society and Its Enemies. Princeton University Press, 1945.

- Reeve, C.D.C. Philosopher-Kings: The Argument of Plato’s Republic. Princeton University Press, 1988.

- Taylor, A.E. Plato: The Man and His Work. Methuen & Co., 1926.

|

|

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|