Home » Social Thinkers » Durkheim

EMILE DURKHEIM

Émile Durkheim (1858-1917) was a French sociologist who established sociology as a legitimate academic discipline and is considered one of the founding fathers of modern sociology alongside Max Weber and Karl Marx. Born into a Jewish family in Lorraine, France, Durkheim initially pursued rabbinical studies before shifting to secular education at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris.

Durkheim’s intellectual development was shaped by the French Enlightenment tradition, particularly Auguste Comte’s positivism, which emphasized scientific methods for studying society. He was also influenced by Herbert Spencer’s evolutionary sociology and Montesquieu’s comparative approach to social institutions. His work emerged during France’s Third Republic, a period of rapid social transformation following military defeat and political upheaval.

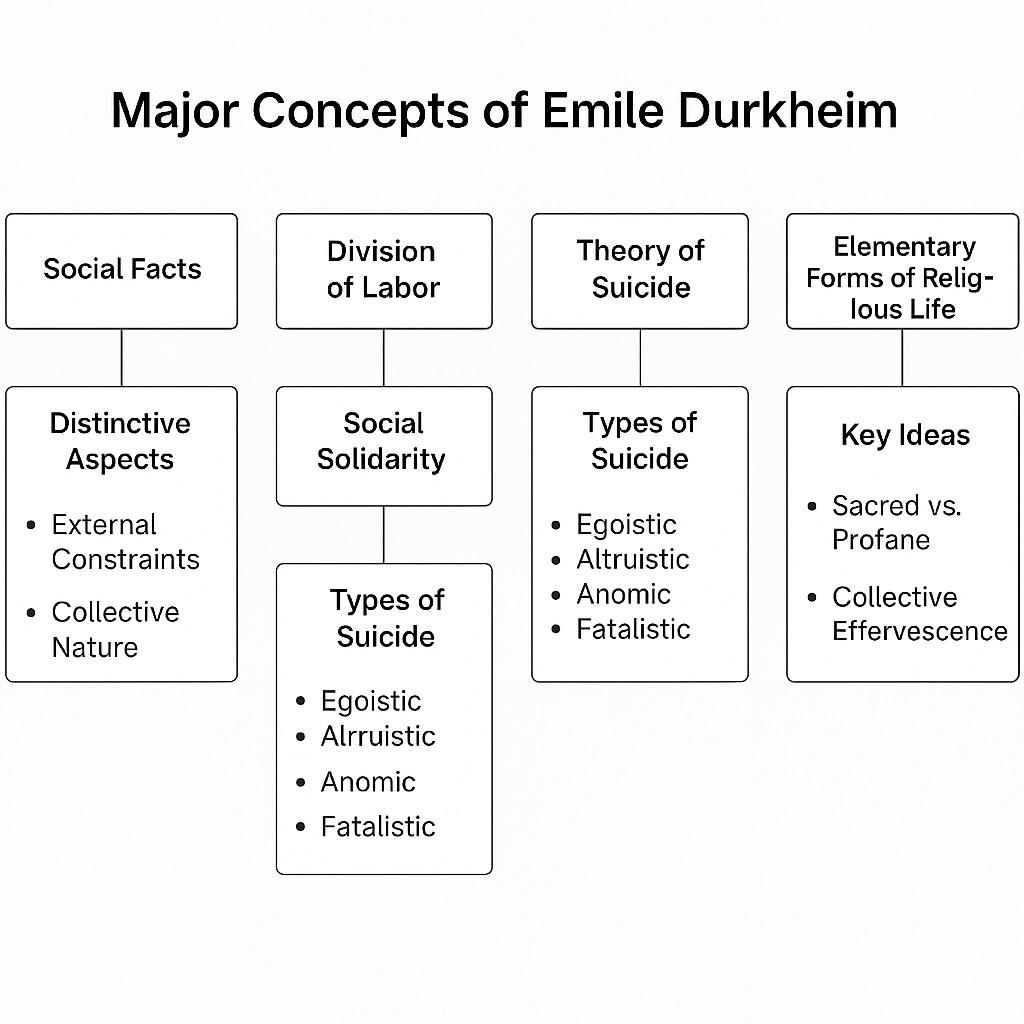

As France’s first professor of sociology at the University of Bordeaux (1887) and later at the Sorbonne, Durkheim sought to establish sociology’s scientific legitimacy through empirical research. His major works include “The Division of Labor in Society” (1893), “The Rules of Sociological Method” (1895), “Suicide” (1897), and “The Elementary Forms of Religious Life” (1912), which collectively established foundational concepts for understanding social solidarity, social facts, and collective consciousness.

Mechanical and Organic Solidarity

In The Division of Labor in Society (1893), Durkheim addresses the fundamental question of social order: what holds society together as it evolves from simple to complex forms? His analysis reveals two distinct types of social solidarity that correspond to different stages of social evolution and different mechanisms of social integration. Mechanical solidarity characterizes traditional, pre-industrial societies where social cohesion derives from similarity and shared collective consciousness. The term “mechanical” suggests that social unity operates like a machine where identical parts perform similar functions and can be substituted for one another without disrupting the whole. In mechanically solidaristic societies, individuals resemble one another in their beliefs, values, practices, and life experiences. The collective consciousness—defined by Durkheim as “the totality of beliefs and sentiments common to average citizens of the same society”—is extensive, intense, and determinate. It is extensive because it encompasses most aspects of individual life, leaving little room for personal variation. It is intense because shared beliefs and values are deeply felt and emotionally charged. It is determinate because it provides clear, specific guidance for behavior in all situations.

The social structure of mechanical solidarity is segmental, consisting of similar, relatively autonomous units like clans, tribes, or villages. Each segment is largely self-sufficient and could theoretically exist independently of others. Social differentiation is minimal, with individuals performing similar roles and possessing similar skills. The division of labor is rudimentary, based primarily on age and sex differences rather than specialized occupational roles. Legal systems in mechanically solidaristic societies emphasize repressive or penal law, where crimes are viewed as offenses against the collective consciousness requiring punishment to restore moral order. The purpose of punishment is not primarily to deter future crimes or rehabilitate offenders but to reaffirm collective values and express social outrage against norm violations.

Individual personality in mechanical solidarity is minimal because personal consciousness is largely absorbed into collective consciousness. As Durkheim observes, “the individual does not appear…the individual is absorbed into the collective.” People think, feel, and act in similar ways because they share the same social experiences and moral frameworks. Individual differences are viewed as deviations from the collective norm rather than expressions of personal uniqueness. Social control operates through the immediate presence of the community, with deviance quickly detected and sanctioned through informal mechanisms like gossip, ostracism, or ritual punishment.

Organic solidarity emerges in modern, industrial societies where social cohesion results from interdependence created by the division of labor. The term “organic” suggests that social unity operates like a biological organism where different parts perform specialized functions that contribute to the survival of the whole. In organically solidaristic societies, individuals differ from one another in their occupations, skills, experiences, and perspectives, yet this very differentiation creates mutual dependence that binds society together. The division of labor produces specialized roles that make individuals dependent on others for goods and services they cannot produce themselves.

The collective consciousness in organic solidarity becomes less extensive, less intense, and more indeterminate. It is less extensive because it covers fewer aspects of individual life, allowing greater personal autonomy and individual variation. It is less intense because shared beliefs are more abstract and less emotionally charged. It is more indeterminate because it provides general principles rather than specific behavioral prescriptions, requiring individuals to interpret and apply these principles to particular situations. The collective consciousness focuses on abstract values like individual dignity, justice, and rational cooperation rather than concrete practices and detailed moral codes.

Legal systems in organic solidarity emphasize restitutive law, which focuses on restoring disrupted relationships rather than punishing offenses against collective sentiments. Contract law, commercial law, and administrative law become prominent because they regulate the complex relationships created by the division of labor. The purpose of legal intervention is to restore normal functioning when specialized relationships break down, not to express moral condemnation or reaffirm collective values.

Individual personality develops extensively in organic solidarity as the weakening of collective consciousness allows personal uniqueness to emerge. Durkheim notes that “each individual depends more closely upon society the more labor is divided; and, on the other, the activity of each is more personal, the more specialized it is.” This apparent paradox—increasing social dependence accompanied by increasing individuation—represents the distinctive characteristic of modern society. Individuals become more different from one another while becoming more dependent on one another.

However, Durkheim recognizes that the division of labor does not automatically produce organic solidarity and can lead to pathological forms that disrupt social integration. The anomic division of labor occurs when rapid social change disrupts regulatory mechanisms, leaving individuals without clear norms to guide their specialized activities. Professional and occupational groups lack adequate moral authority to regulate their members’ behavior, resulting in conflict, exploitation, and social disorder. The forced division of labor emerges when external constraints rather than natural talents and preferences determine occupational placement. Social inequality, inherited privilege, and discrimination prevent the optimal matching of individuals to specialized roles, creating resentment, inefficiency, and social instability.

Durkheim’s solution to these pathological conditions involves strengthening intermediate institutions, particularly professional associations, that can provide moral regulation for specialized occupational groups. These “corporations” would serve as mediating structures between individuals and the state, offering moral guidance, social support, and collective representation for members of different occupations. They would help restore the balance between social integration and individual autonomy that characterizes healthy organic solidarity.

Émile Durkheim’s Suicide: The Social Determination of Individual Behavior (1897) fundamentally redefines suicide from a solely personal or pathological act to one deeply embedded in the fabric of society. Durkheim argued that suicide rates are not random or merely the outcome of individual mental states; instead, they are “social facts”—observable, stable patterns that reflect the underlying structure and health of a society. By analyzing statistical data across different social groups, he demonstrated that variations in suicide rates correlate strongly with the degree of social integration and regulation present within a society.

Durkheim rejected explanations based purely on psychological or biological factors, noting that if suicide were simply the result of individual mental illness or hereditary predispositions, its occurrence should be more uniformly distributed across populations. Instead, he observed that suicide rates remain remarkably consistent within specific social groups while varying significantly between them. This indicates that social forces—such as the strength of family ties, religious practices, and community bonds—play a critical role in determining an individual’s vulnerability to suicide.

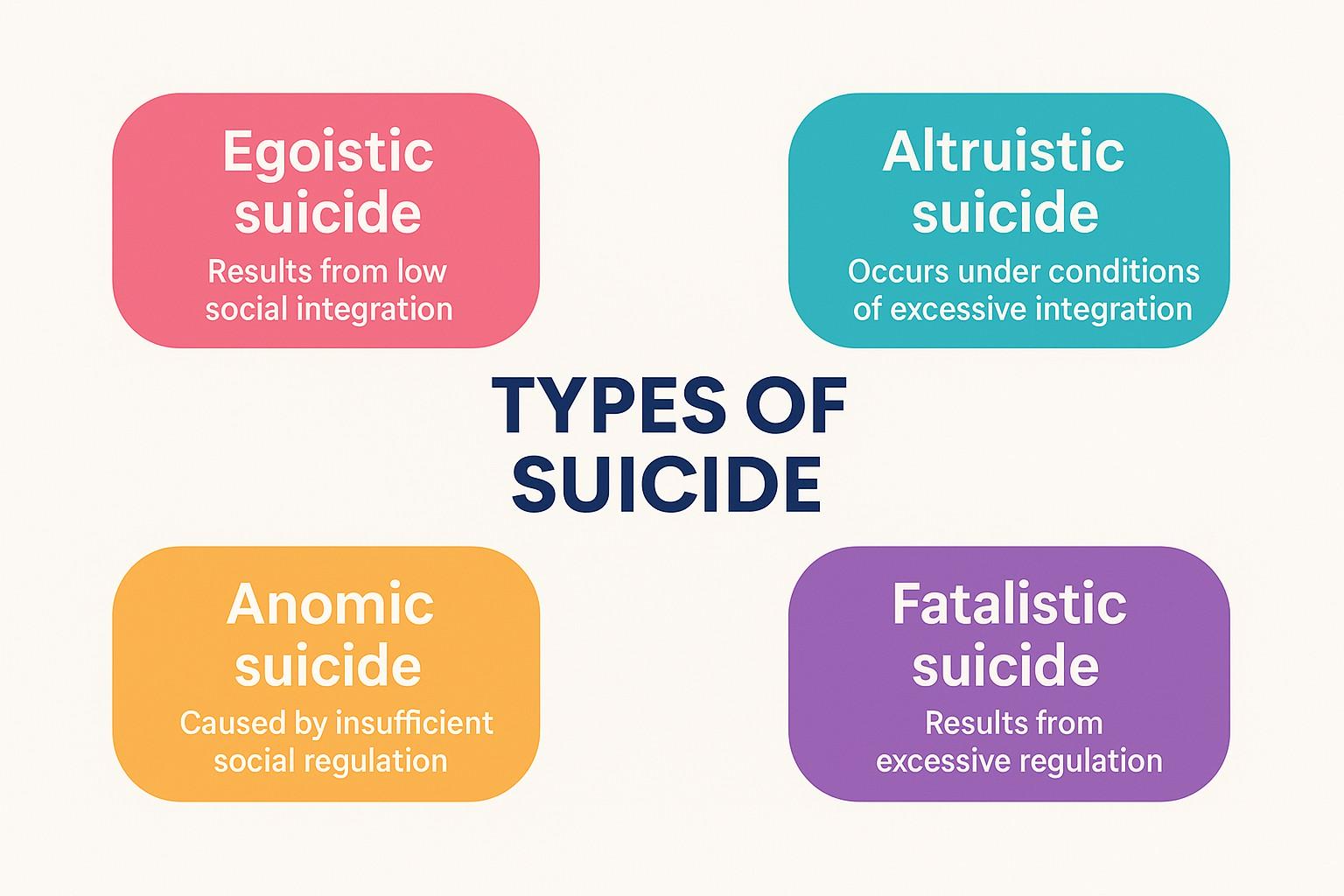

Central to Durkheim’s theory is the idea that social life can be understood through two key dimensions: social integration, which refers to the extent to which individuals are connected to groups and collective life, and social regulation, which denotes the degree of control or guidance that societal norms and institutions impose on individual behavior. When these dimensions are out of balance, the risk of suicide increases, and Durkheim identified four distinct types of suicide that emerge from different combinations of integration and regulation.

Egoistic suicide results from low social integration. Individuals who feel disconnected from family, community, or broader social networks lack the support and shared meaning necessary to cope with personal crises. This isolation breeds what Durkheim called “excessive individualism”—where personal interests and self-reflection dominate without the mitigating influence of collective bonds. The elevated suicide rates observed among groups like unmarried people, Protestants (who often emphasize personal interpretation over communal rituals), and urban residents underline the importance of social cohesion in providing meaning and support.

In contrast, altruistic suicide occurs when social integration is excessively high. In such cases, the individual is so absorbed by the collective identity that personal existence becomes secondary to the interests or honor of the group. Examples include cases like military personnel or religious martyrs, where the act of suicide is seen as a noble sacrifice in the name of duty, loyalty, or honor. Here, the overwhelming group consciousness effectively erases individual boundaries, making self-sacrifice a socially endorsed act.

Anomic suicide is linked to insufficient social regulation—a state often described as “anomie.” During periods of rapid social, economic, or personal change, the established norms that once guided behavior may break down. Whether due to sudden wealth, devastating financial crises, or significant personal disruptions like divorce, individuals find themselves in a state of normlessness, where old standards no longer apply and new ones have yet to emerge. This loss of clear societal guidance creates unfulfilled aspirations and chronic dissatisfaction, ultimately leading to despair and self-destruction.

Lastly, fatalistic suicide arises under conditions of excessive regulation. Although less common in modern settings, this form occurs when a person is subject to oppressive control so stringent that no hope remains for personal change or liberation. Examples of fatalistic suicide can be seen among individuals in repressive institutions or oppressive relationships, where severe external constraints leave them with an overwhelming sense of futility and entrapment. Overall, Durkheim’s work illustrates that the roots of suicide extend far beyond the individual; they are the products of broader societal forces.

The Elementary Forms of Religious Life

Published in 1912, The Elementary Forms of Religious Life marks a major milestone in the intellectual journey of Émile Durkheim. It represents the culmination of his lifelong project to understand the fundamental forces that shape human society. In this landmark work, Durkheim presents a detailed exploration of religion, not merely as a system of beliefs but as the most fundamental institution that reveals the intricate relationship between individual consciousness and collective social life.

Durkheim’s approach to religion is firmly rooted in his commitment to a scientific and empirical sociology. Rather than examining complex religions such as Christianity, Hinduism, or Islam, which have evolved over centuries and are interwoven with theology and institutional structures, Durkheim deliberately focuses on what he considered the most elementary form of religion: the totemic system of Australian Aboriginal tribes. For him, these early religious systems were simpler and more transparent, providing a clearer view of the fundamental elements of religious life before they became obscured by layers of cultural evolution and dogma. Through this methodological choice, Durkheim aims to strip religion down to its bare essentials and uncover the social processes at its foundation. He believes that by studying the origin of religion in its simplest forms, one can identify the social forces that give rise to religious beliefs, symbols, and rituals. He does not consider these early religious forms to be primitive or irrational, but rather as the most basic expression of the social function of religion.

Durkheimdefines religion as:

A unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things—that is to say, things set apart and forbidden—beliefs and practices which unite into one single moral community called a Church, all those who adhere to them.”

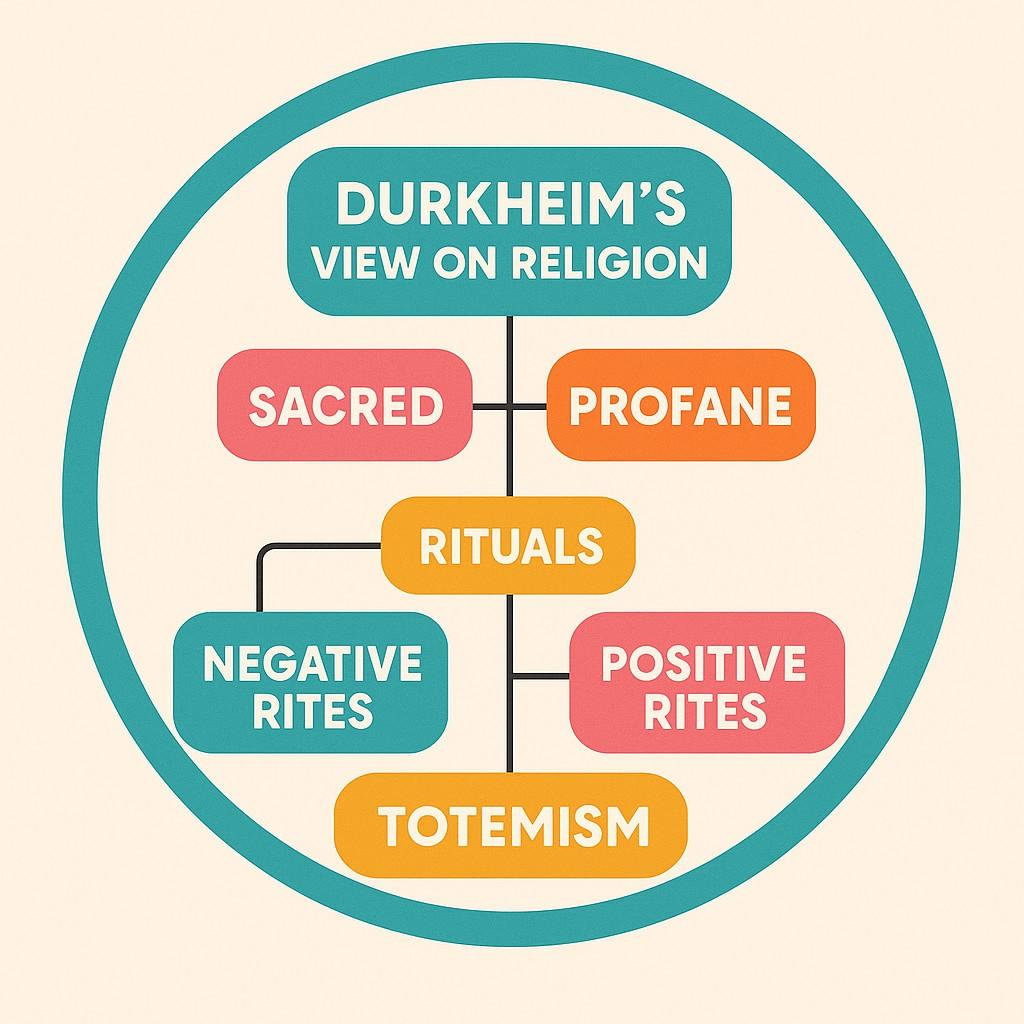

This definition carries several key elements. First, religion includes both beliefs (ideas, doctrines, and understandings of sacred things) and practices (rituals, ceremonies, and customs). Second, the object of religious reverence is not everyday life or ordinary things, but the sacred—those things which are distinct, special, and prohibited from everyday use. Third, religion functions by forming a moral community—a collective of people who share these beliefs and practices. This collective character distinguishes religion from individual spirituality or philosophical reflection. Religion is inherently social.

Central to Durkheim’s analysis is the distinction between the sacred and the profane. According to him, this binary is the most elementary and universal feature of all religious systems. The sacred refers to things that are set apart, revered, and treated with awe, while the profane includes all things mundane and part of the regular, day-to-day world. The sacred is protected by taboos and religious rules, and crossing this boundary—such as touching a sacred object in an unworthy state—can lead to symbolic or real consequences.

This sharp distinction between sacred and profane also requires the existence of rituals to mediate between the two realms. People must undergo processes of purification or preparation to approach the sacred. Rituals—such as fasting, silence, and abstinence—help reinforce this separation and maintain social discipline. These rules are not arbitrary; they serve to preserve the respect for the sacred and the moral order that society depends on.

Durkheim’s examination of Aboriginal totemism provides concrete evidence of how religion operates as a social force. In totemic systems, each clan is associated with a particular animal or plant species, referred to as the totem. This totem is not merely a symbol—it is considered the spiritual ancestor and protector of the clan. It is forbidden to kill or consume the totem species except during certain ceremonial events, and clan members feel a deep sense of reverence for it.

What makes Durkheim’s insight powerful is his argument that the totem is a symbolic representation not of an external divine being, but of the society itself. When people gather to worship the totem, they are in fact expressing their collective identity and reverence for the social group. The totem, therefore, is a visible manifestation of the invisible force of society. In Durkheim’s words, “the god of the clan… is only the clan itself, transfigured and imagined in the form of the totem.” This insight leads to Durkheim’s larger argument: religion is a social construction that represents and reinforces the collective consciousness. When people believe they are worshipping divine powers, they are actually responding to the power of the group—the shared norms, values, and emotional energy that bind people together. Religion is the way society expresses and celebrates itself, giving symbolic form to its own moral authority.

To explain how these religious experiences are generated, Durkheim introduces the concept of collective effervescence. This term refers to the intense emotional energy that arises when people gather for rituals and ceremonies. During these moments, individuals transcend their personal concerns and feel uplifted by a sense of unity, purpose, and power. This shared emotional state creates the perception of something greater than oneself—a sacred force—that Durkheim identifies as the emotional basis of religion. This collective effervescence not only strengthens social bonds, but also reinforces shared values and beliefs. It makes the sacred real by emotionally charging certain symbols, actions, or times with special meaning. These emotionally intense experiences are remembered, passed down, and institutionalized, forming the basis of religious traditions.

Durkheim identifies various types of religious rites that contribute to different aspects of social life. Negative rites, such as fasting and silence, are used to separate the sacred from the profane and prepare individuals for contact with sacred things. Positive rites include acts like sacrifices, offerings, or feasts that bring the group into contact with the sacred and renew their collective energy.

In Durkhiem’s view, religion is not simply about belief—it is an active, dynamic social process that maintains the moral fabric of society. He goes further to argue that the very categories through which we think—time, space, classification, causality—originate in religious (and therefore social) contexts. Sacred festivals create concepts of time; ceremonial sites structure spatial understanding; categories like plant, animal, or human are structured according to totemic classification. Even the concept of force or cause arises from the experience of collective power in religious rituals. This suggests that society provides the blueprint for how individuals think, categorize, and interpret the world.

Durkheim explores how modern secular societies might replace traditional religion. He suggests that institutions like the state, education, and civic rituals can serve similar functions by providing shared symbols and collective emotions. However, he recognizes challenges posed by individualism and rationalism, which weaken collective unity. Still, Durkheim remains hopeful that society will create new forms of collective representation to preserve moral cohesion. For him, religion reflects the moral force of society itself, and studying it offers deep insights into how social order, meaning, and unity are maintained across time and cultures.

Critiques of Émile Durkheim:

1. Oversocialized View of the Individual

Durkheim emphasizes that individuals are shaped by social facts—external, constraining norms and values. Critics argue this presents an overly deterministic view, where human agency, individuality, and resistance are underplayed. Individuals appear as passive recipients of social forces, leaving little room for creativity or dissent.

2. Neglect of Conflict and Power

Durkheim’s focus on social cohesion and stability ignores conflict, inequality, and power dynamics. His functionalist lens assumes institutions exist to maintain order, but Marxist and conflict theorists argue that institutions often benefit dominant groups and reproduce oppression rather than serve collective good.

3. Simplistic Typologies

In Suicide and The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, Durkheim often categorizes social phenomena into rigid types (e.g., types of suicide, sacred vs profane). Critics find these typologies too schematic and reductive, failing to capture the fluidity and complexity of human behavior and belief.

4. Methodological Positivism

Durkheim’s commitment to applying scientific methods to study society—treating social facts “as things”—has been criticized for being reductionist. Interpretivist sociologists argue that meanings and subjective experiences cannot be studied like natural science objects; they require understanding from within.

5. Ethnocentrism in Studying Religion

In studying Aboriginal totemism, Durkheim sought universal truths about religion but relied on colonial-era ethnographic sources. Scholars argue this imposed Western categories onto non-Western societies and generalized religious concepts from a narrow cultural context, making his conclusions ethnocentric.

References

Durkheim, É. (1982). The Rules of Sociological Method (S. Lukes, Ed., W. D. Halls, Trans.). New York: The Free Press. (Original work published 1895)

Durkheim, É. (2014). The Division of Labor in Society (W. D. Halls, Trans.). New York: Free Press. (Original work published 1893)

Durkheim, É. (2006). On Suicide (R. Buss, Trans.). London: Penguin Classics. (Original work published 1897)

Durkheim, É. (1995). The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (K. E. Fields, Trans.). New York: The Free Press. (Original work published 1912)

|

|

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|

Social Facts: The Foundation of Sociological Science

Durkheim’s revolutionary contribution to sociology begins with his concept of social facts, which he presents in The Rules of Sociological Method (1895) as the distinctive object of sociological inquiry. Social facts represent a fundamental departure from individualistic explanations of human behavior, establishing sociology as an autonomous science with its own subject matter. Durkheim defined social facts as “ways of acting, thinking, and feeling, external to the individual, and endowed with a power of coercion, by reason of which they control him.” This definition contains three essential characteristics that distinguish social facts from individual psychological phenomena and establish their scientific legitimacy.

The first characteristic, externality, means that social facts exist independently of any particular individual’s consciousness or will. These phenomena possess an objective reality that transcends individual subjectivity. When Durkheim writes, “when I fulfill my obligations as brother, husband, or citizen, when I execute my contracts, I perform duties which are defined, externally to myself and my acts, in law and in custom,” he emphasizes that social obligations existed before individuals were born and will persist after they die. Language provides a clear example—we do not create the grammatical rules we follow; they exist as external constraints that we must accept to communicate effectively. Similarly, legal systems, educational curricula, monetary systems, and moral codes all represent external social facts that shape individual behavior regardless of personal preferences.

The second characteristic, constraint, refers to the coercive power that social facts exercise over individuals. This constraint becomes evident when we attempt to resist social expectations or violate established norms. Durkheim notes that “if I attempt to violate the law, it reacts against me so as to prevent my act before its accomplishment, or to nullify my violation by restoring the damage.” The constraint operates through various mechanisms—legal sanctions, social disapproval, economic penalties, or psychological pressure. Try speaking a language incorrectly, violating dress codes, or ignoring social etiquette, and you will experience the constraining force of social facts. This constraint is not merely external but becomes internalized through socialization, creating what Durkheim calls “social pressure” that guides individual behavior even in the absence of external surveillance.

The third characteristic, generality, indicates that social facts are collective phenomena shared across society rather than individual idiosyncrasies. They represent common ways of acting, thinking, and feeling that transcend individual variations. Durkheim emphasizes that social facts are “general because they are collective” and “collective because they are general.” This generality distinguishes social facts from individual psychological states or exceptional behaviors. Crime rates, suicide rates, marriage patterns, and educational achievements all demonstrate this generality—they represent collective tendencies that manifest consistently across populations while varying between different societies or social groups.

Durkheim’s methodological innovation lies in his insistence on treating social facts as “things” that can be studied objectively through empirical observation. This approach requires sociologists to set aside preconceptions and study social phenomena through their external manifestations rather than through subjective interpretations or introspective analysis. Social facts must be explained by other social facts, not by individual psychology or biological factors. This methodological principle establishes sociology’s scientific autonomy while providing concrete guidelines for sociological research. The study of social facts reveals the existence of a “social realm” that operates according to its own laws and possesses its own reality, distinct from but influencing individual consciousness and behavior.