Home » Social Action

Social Action

Index

Introduction

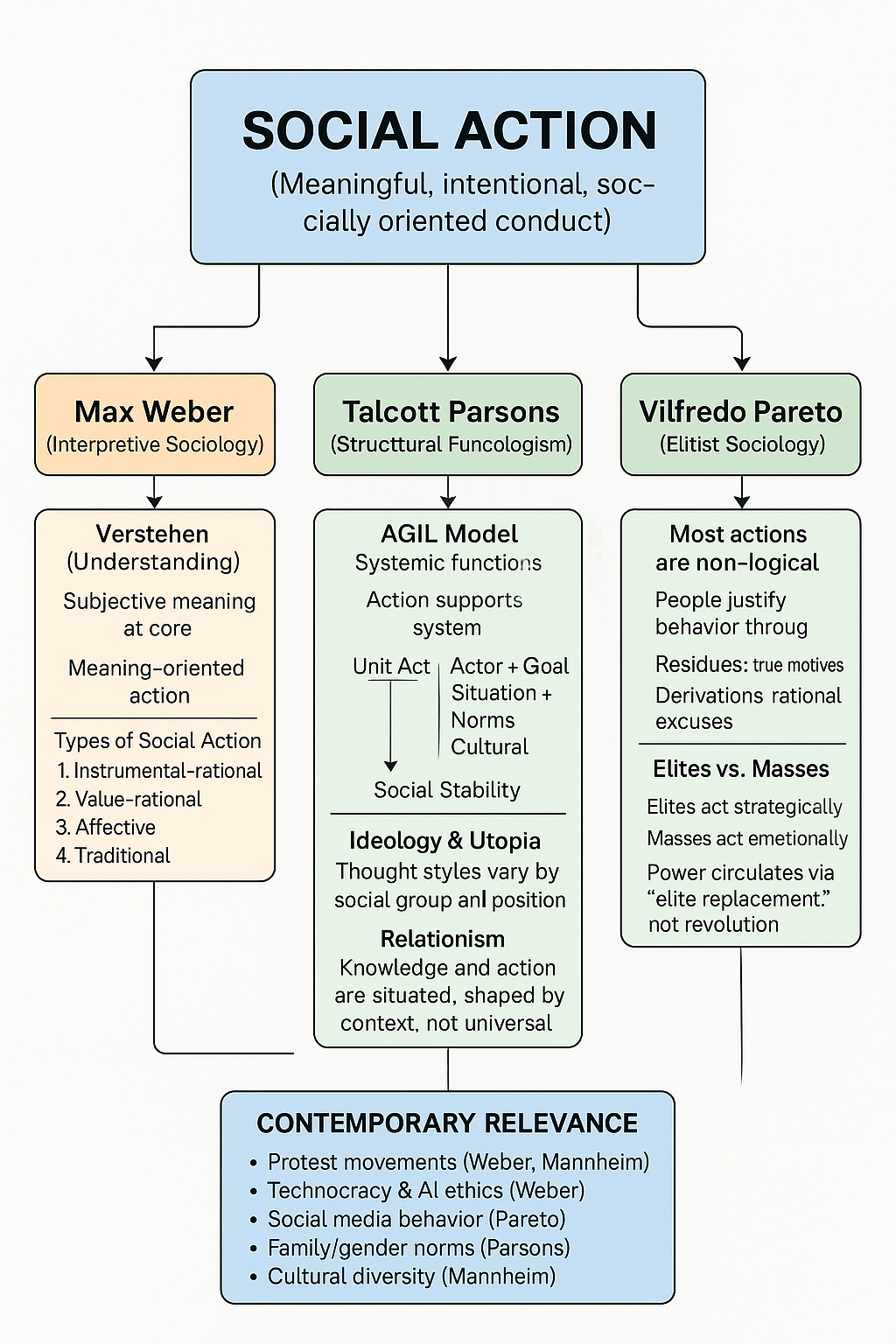

Sociology as a discipline is fundamentally concerned with the study of human action and interaction within the complex framework of society. At the core of this scholarly inquiry lies the concept of social action—a term that emphasizes not merely what people do, but why they do it and how their actions are embedded in an intricate web of social meanings, relationships, and structures. Social action theory seeks to uncover the motivations, intentions, and subjective meanings behind individual or group behavior and to understand how these actions shape and are simultaneously shaped by broader societal forces.

The concept of social action represents one of sociology’s most foundational theoretical constructs, bridging the gap between individual agency and social structure. While the term “social action” is most commonly associated with Max Weber’s interpretive sociology, the concept has been enriched and reinterpreted by several other prominent thinkers, including Talcott Parsons, Karl Mannheim, and Vilfredo Pareto. Each of these theorists brings a distinctive analytical lens—ranging from interpretive sociology to functionalism, phenomenology, and elite theory—offering valuable insights into the nature, types, and functions of human action in social contexts.

Max Weber: The Architect of Social Action Theory

Weber’s Interpretive Approach

Max Weber (1864–1920), oen regarded as the father of interpretive sociology,

placed Verstehen (German for “understanding”) at the center of sociological

inquiry. For Weber, the primary task of sociology was to understand human

behavior from the actor’s point of view, emphasizing the subjective meaning

that individuals attach to their actions. His concept of social action laid the

foundation for a micro-level, meaning-oriented approach to the study of

society that continues to influence sociological theory and research

methodology.

Weber’s interpretive approach represents a fundamental departure from

positivist sociology, which sought to apply natural science methods to social

phenomena. Instead of focusing solely on observable behavior and external

causation, Weber insisted that sociologists must understand the internal logic

and subjective meaning that guide human action. This approach recognizes

that human beings are meaning-making creatures who act based on their

interpretations of social situations, their values, and their understanding of

appropriate behavior.

Weber defined social action as conduct that is oriented toward the behavior of

others and takes their existence into account. This emphasis on subjective

meaning distinguishes social action from mere reaction or reflexive behavior.

It insists that sociologists must study how and why people act, not just what

they do, and that understanding requires empathetic interpretation of the

actor’s perspective. Weber’s approach acknowledges that the same external

behavior can have entirely different meanings depending on the actor’s

intentions, cultural context, and social situation.

Weber’s Four Types of Social Action

Weber categorized social actions into four ideal types based on the motivation behind them, creating a typology that has become one of the most influential frameworks in sociology. These ideal types represent pure forms of action that rarely exist in isolation but serve as analytical tools for understanding the logic behind different kinds of social behavior

Instrumental-rational action, also known as means-end rationality or goal-rational action, represents actions motivated by the calculation of the most efficient means to achieve a specific goal. This type of action involves systematic consideration of alternatives, evaluation of costs and benefits, and selection of the most effective strategy for achieving desired outcomes. Examples include an entrepreneur investing in green technology for economic return, a student choosing a career path based on salary prospects, or a politician craing policy positions to maximize electoral success. This type of action embodies the spirit of modern capitalism and bureaucratic organization, where efficiency and effectiveness are paramount concerns.

Value-rational action consists of actions undertaken in obedience to a value, regardless of consequences or practical considerations. This type of action is guided by ethical, religious, aesthetic, or other values that the actor considers intrinsically important. The actor pursues the action because it is consistent with their fundamental beliefs, even if it may lead to negative practical outcomes. Examples include a person fasting for religious reasons despite health risks, a whistleblower revealing corruption despite personal consequences, or an environmental activist engaging in civil disobedience to protest climate change. Value-rational action demonstrates the power of deeply held beliefs to motivate behavior that may appear irrational from a purely instrumental perspective.

Affective action represents actions driven by emotional states, feelings, or spontaneous reactions to situations. This type of action is characterized by immediate emotional response rather than calculated deliberation or adherence to abstract values. Examples include crying during a funeral, cheering at a sporting event, expressing anger during a confrontation, or showing affection toward loved ones. Affective action highlights the emotional dimension of human behavior and the ways in which feelings can motivate social conduct.

Traditional action refers to actions guided by customs, habits, or ingrained patterns of behavior that have been passed down through generations. This type of action is based on established ways of doing things rather than rational calculation or conscious value commitment. Examples include lighting lamps during Diwali without questioning its origin, following traditional wedding ceremonies, or maintaining customary forms of greeting and social interaction. Traditional action demonstrates the power of cultural inheritance and social learning in shaping behavior.

Weber emphasized that real-world actions oen involve a blend of these types, but the typology helps understand the logic of action in different contexts. The same behavior might be motivated by different types of rationality depending on the actor and situation, and understanding these motivations is crucial for sociological analysis

Weber on Rationalization and Disenchantment

Weber’s typology also links to his broader theory of rationalization—the increasing dominance of instrumental-rational action in modern societies. This shi, he argued, leads to the “disenchantment of the world,” where religious, emotional, and traditional forms of action decline in importance, and bureaucratic efficiency dominates social life. Social life becomes increasingly governed by logic, rules, and impersonal structures, leading to what Weber famously termed the “iron cage” of rationality.

The process of rationalization involves the systematic organization of social life according to principles of efficiency, predictability, and control. Traditional and value-rational forms of action are gradually replaced by instrumental-rational calculation, as institutions like bureaucracy, capitalism, and science extend their influence over more areas of human experience. While this process brings many benefits, including technological advancement and organizational efficiency, Weber was concerned about its potential negative consequences for human freedom, creativity, and meaningful social relationships.

Talcott Parsons: Social Action within the System

Parsons and the AGIL Framework

Talcott Parsons (1902–1979), a leading American functionalist, developed a more structural and systemic view of social action that moved beyond Weber’s focus on individual meaning. While influenced by Weber’s work, Parsons shied attention from the individual and subjective aspects of action to focus on how actions are embedded in and contribute to social systems. His approach represents a macro-level perspective that emphasizes the ways in which individual actions serve broader social functions

According to Parsons, every social system must perform four basic functions to maintain itself and adapt to its environment. These functions are captured in the AGIL model: Adaptation involves adjusting to the external environment and mobilizing resources to meet system needs. Goal Attainment refers to defining and achieving collective goals and priorities. Integration involves coordinating different parts of the system and maintaining internal coherence. Latency, also known as pattern maintenance, involves preserving cultural values, motivation, and commitment to the system.

Social action, for Parsons, is not merely individual behavior but part of this systemic functioning. Every action is understood as a contribution to the maintenance of social order and the fulfillment of system requirements. Individual actions are seen as responses to system needs and as mechanisms through which social systems maintain themselves over time.

The Unit Act and the Social System

Parsons developed the concept of the “unit act” as the basic analytical unit of

his theory. A unit act has four essential components: an actor who performs

the action, a goal or end toward which the action is directed, a situation that

includes both the means available to the actor and the conditions that

constrain action, and norms and values that guide and evaluate the action.

This framework emphasizes that social action is always embedded in a

normative context that shapes both the actor’s choices and the evaluation of

those choices by others.

For Parsons, social action is shaped and regulated by three interconnected

systems: the cultural system, which provides values and norms that guide

action; the social system, which organizes roles and institutions that structure

social relationships; and the personality system, which provides motivation

and psychological orientation for action. These systems work together to

ensure that individual actions contribute to social stability and integration.

Parsons viewed social action as systematically structured phenomena that is

rational, patterned, and oriented toward social equilibrium. Unlike Weber’s

emphasis on subjective meaning and individual interpretation, Parsons

focused on how actions are regulated by social roles, institutional

expectations, and shared cultural values. This approach emphasizes

consensus, stability, and the ways in which social systems maintain themselves

through the coordinated actions of their members.

Critique and Legacy

Critics argue that Parsons overemphasized stability and consensus while underplaying conflict, power, and social change. His theory has been criticized for its conservative bias, its difficulty in explaining social transformation, and its tendency to assume that existing social arrangements are functional and beneficial. However, Parsons’ theory remains foundational for understanding how individual actions contribute to systemic integration and how institutions regulate action through norms and roles. His work continues to influence contemporary sociology, particularly in areas such as socialization, social control, and institutional analysis.

Karl Mannheim: Social Action and Ideology

Mannheim’s Sociology of Knowledge

Karl Mannheim (1893–1947), a sociologist associated with the sociology of

knowledge, brought an epistemological dimension to the study of social action

that emphasized the relationship between knowledge, ideology, and social

position. He argued that ideas and worldviews are socially conditioned,

including the motivations and interpretations that guide human action. This

perspective highlights the ways in which social location shapes not only what

people think but also how they act and understand their actions.

In his landmark work, “Ideology and Utopia” (1936), Mannheim proposed that

different social groups possess different consciousnesses or “thought styles”

that shape their interpretations of the world and their approaches to social

action. These thought styles are not merely individual preferences but are

rooted in the social, economic, and historical positions of different groups.

Thus, social action cannot be separated from the ideological position and

social location of the actor.

For Mannheim, social action is fundamentally shaped by the intellectual and

ideological context of the actor, influenced by their historical position

including factors such as class, generation, and social group membership, and

constructed through collective worldviews or “styles of thought” that provide

frameworks for understanding and acting in the world. This approach

emphasizes that understanding social action requires attention to the broader

intellectual and cultural context within which actors operate.

Relationism and Situated Knowledge

Mannheim developed a theory of relationism—an approach that emphasizes the relativity of knowledge without collapsing into complete relativism. In this view, actions must be understood in relation to the social and historical location of the actor, but this does not mean that all perspectives are equally valid or that objective understanding is impossible. Rather, it suggests that knowledge and action are always situated within particular social contexts that shape their meaning and significance.

This perspective suggests that a factory worker and a factory owner may engage in the same behavior, such as voting in an election, but the meaning and purpose of their actions differ due to their different class positions and the ideological frameworks that emerge from those positions. The worker’s vote might be motivated by concerns about economic security and social justice, while the owner’s vote might be motivated by concerns about business regulation and tax policy. Understanding these different motivations requires attention to the social positions and ideological contexts of the actors involved.

Mannheim vs. Weber and Parsons

While Weber focused on individual meaning and subjective interpretation,

and Parsons emphasized systemic integration and functional requirements,

Mannheim foregrounded collective mentalities and the ways in which social

groups interpret reality and act within it. His theory encourages sociologists

to consider ideological motivations and the ways in which social position

shapes both thought and action. This perspective makes Mannheim’s work

especially relevant for studying political action, revolution, social movements,

and other forms of collective behavior where ideology and group

consciousness play central roles.

Mannheim’s approach also differs from Weber’s in its emphasis on the social

rather than individual basis of meaning. While Weber focused on the

subjective meaning that individuals attach to their actions, Mannheim

emphasized the ways in which these meanings are shaped by collective

ideologies and social positions. This perspective provides important insights

into how social action is influenced by broader cultural and political contexts.

Vilfredo Pareto: Action, Residues, and Elites

Pareto’s Sociological Psychology

Vilfredo Pareto (1848–1923), an Italian sociologist and economist, approached

social action from a psychological and elitist perspective that challenged many

of the assumptions of other social theorists. He argued that much of human

behavior is not rational in the conventional sense but is driven by non-logical

actions that are later justified through post-hoc rationalization. This

perspective represents a significant departure from Weber’s emphasis on

rational action and Parsons’ focus on normative integration.

Pareto distinguished between logical actions and non-logical actions as

fundamentally different types of social behavior. Logical actions are rational

and means-end oriented, similar to Weber’s instrumental-rational action,

involving systematic consideration of alternatives and selection of effective

means to achieve desired goals. Non-logical actions, by contrast, are

emotionally driven or habitual actions that are not based on clear logical

reasoning but emerge from deeper psychological drives and social instincts.

However, for Pareto, the bulk of human behavior falls into the non-logical

category, particularly in areas such as politics, religion, and social

relationships. This perspective suggests that rational choice models of social

action may be inadequate for understanding much of human behavior,

particularly in collective contexts where emotional and psychological factors

play dominant roles

Residues and Derivations

Pareto introduced the concepts of “residues” and “derivations” to explain the

relationship between underlying psychological drives and the rational

justifications that people provide for their actions. Residues represent the

deep-seated instincts, sentiments, and emotional drives that actually motivate

behavior. These are relatively stable psychological tendencies that reflect

fundamental human needs and drives. Derivations, on the other hand, are the

rational justifications or explanations that people give for their actions, oen

aer the fact.

For instance, people may join a patriotic movement because of a deep-seated

need for group solidarity and belonging (residue), but they explain their

participation in terms of democratic ideals, national security, or historical

tradition (derivation). The derivation provides a socially acceptable rational

explanation for behavior that is actually motivated by emotional and

psychological factors.

This theory implies that social action is less about calculated rationality and

more about emotional and instinctual drives, particularly in mass behavior and

collective action. It suggests that sociologists should be skeptical of the

rational explanations that people give for their behavior and should instead

look for the underlying psychological and social forces that actually drive

action.

Elite Theory and Circulation of Elites

Pareto also developed an influential theory of elites that has important

implications for understanding social action. He proposed that all societies

are ruled by elites—small groups of people who possess the resources, skills,

and power necessary to dominate social institutions. Social change, according

to Pareto, occurs primarily through the circulation of elites rather than

through fundamental changes in social structure or popular revolution.

Even movements that appear to be democratic or revolutionary do not

eliminate elitism but merely replace one elite with another. This perspective

suggests that much social action, particularly political action, should be

understood in terms of competition between different elite groups rather than

as expressions of popular will or rational choice.

From a social action perspective, Pareto’s theory suggests that elite behavior is

typically strategic and calculated, involving careful consideration of means

and ends in the pursuit of power and influence. Mass behavior, by contrast, is

oen driven by residues—emotional attachments, faith, loyalty, or other

non-rational factors that make ordinary people susceptible to elite

manipulation and control.

Contemporary Relevance of Social Action Theories

Theories of social action remain vital for analyzing contemporary social

phenomena across multiple domains of human experience. In the realm of

political action, protest movements such as farmer protests, climate strikes,

and social justice movements can be examined through multiple theoretical

lenses. Mannheim’s ideological framework helps explain how different social

groups understand and respond to policy issues, while Weber’s concept of

value-rational action illuminates why activists may pursue causes despite

personal costs or uncertain outcomes.

The rise of technocratic governance and debates about artificial intelligence

ethics raise important Weberian concerns about the increasing dominance of

instrumental rationality and the potential for further disenchantment of social

life. As technological solutions are increasingly applied to social problems,

questions arise about the impact on human agency, meaningful social

relationships, and the balance between efficiency and other human values.

Social media behavior provides excellent examples of Pareto’s insights about

the gap between rational justifications and emotional motivations. Much

online activity appears to be driven by residues such as the desire for social

belonging, status competition, and emotional expression, even though users

oen provide rational explanations for their participation. The spread of

misinformation and the formation of echo chambers can be understood

through Pareto’s analysis of how derivations (rational justifications) can mask

non-logical motivations.

Contemporary debates about gender roles, family structures, and social

institutions continue to reflect the kinds of normative regulation that Parsons

analyzed in his work. Even as these norms change, the basic mechanisms

through which societies coordinate expectations and regulate behavior remain

relevant for understanding social action in contemporary contexts.

The globalization of culture and the increasing diversity of modern societies

create new contexts for understanding how social position and cultural

background shape social action. Mannheim’s insights about the relationship

between social location and worldview remain relevant for understanding how

different groups navigate multicultural societies and respond to global

challenges.

References:

- Mannheim, K. (1936). Ideology and utopia: An introduction to the sociology of knowledge. Harcourt, Brace & World.

- Parsons, T. (1937). The structure of social action: A study in social theory with special reference to a group of recent European writers. McGraw-Hill.

- Pareto, V. (1935). The mind and society: A treatise on general sociology (A. Livingston, Ed.; A. Bongiorno & A. Livingston, Trans.). Harcourt, Brace & Company. (Original work published 1916)

- Weber, M. (1978). Economy and society: An outline of interpretive sociology (G. Roth & C. Wittich, Eds.). University of California Press. (Original work published 1922)

Definitions of Social Action

Max Weber defines social action: action is social in so far as by virtue of the subjective meaning attached to it by acting individual it takes account of the behaviour of others and is thereby oriented in its course. It includes all human behaviour when and in so far as the acting individual attaches a subjective meaning to it.

According to Talcott Parsons a social action is a process in the actor-situation system which has motivational significance to the individual actor or in the case of collectivity, its component individuals.

|

|

According to Pareto sociology tries to study the logical and illogical aspects of actions. Every social action has two aspects one is its reality and other is its form. Reality involves the actual existence of the thing and the form is the way the phenomenon presents itself to the human mind. The first is called the objective and the other is called subjective aspects.

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|

Defining Social Action: From Behavior to Meaningful Conduct

In everyday usage, the term “action” is oen used interchangeably with “behavior,” creating conceptual confusion that sociologists have worked to clarify. However, sociologically, these two concepts are fundamentally distinct and carry different analytical weight. Behavior refers to any observable activity of humans or animals, which may or may not be conscious, purposeful, or socially oriented. In contrast, social action refers specifically to intentional, meaningful conduct that is oriented toward others in a social context and carries subjective significance for the actor.

The defining characteristics of social action include several key elements that distinguish it from mere behavior or biological response. First, subjective meaning is central—the action is carried out with intention and awareness, involving conscious deliberation or at least some level of cognitive processing. Second, orientation toward others is essential—the action anticipates the presence, response, or behavior of others, even if those others are not physically present. Third, cultural embedding shapes the action—it is influenced by norms, values, and social contexts that give it meaning within a particular society or group. Finally, symbolic significance is inherent—the action carries meaning beyond its immediate physical manifestation, serving as a form of communication or expression within social relationships.

For example, walking down a street is mere behavior—a physical movement from one location to another. However, walking down a street to attend a protest rally, to communicate dissent, to accompany a friend in need, or to participate in a religious procession becomes social action because it involves intentional meaning, orientation toward others, and symbolic significance within a social context. The same physical movement takes on entirely different sociological meaning depending on the actor’s intentions, the social situation, and the cultural framework within which it occurs.

This distinction between behavior and social action is crucial for sociological analysis because it emphasizes the importance of understanding not just what people do, but why they do it and how their actions fit into broader patterns of social life. It also highlights the interpretive dimension of sociology—the need to understand social phenomena from the perspective of the actors themselves, rather than imposing external explanations based solely on observable outcomes.