Home » Social Thinkers » Peter M. Blau

Peter M. Blau

Index

Introduction

Peter Michael Blau (1918–2002), an Austrian-American sociologist, is widely regarded as a pivotal figure in modern sociology, known for his groundbreaking contributions to social exchange theory, organizational sociology, and social stratification. Born in Vienna, Austria, Blau’s early life was profoundly shaped by the socio-political upheavals of 1930s Europe. As a secular Jew, he faced persecution under the Nazi regime, including brief imprisonment aer attempting to flee Austria following the 1938 Anschluss. His eventual escape to the United States, facilitated by a refugee scholarship to Elmhurst College in Illinois, marked the beginning of his academic journey. These experiences of displacement and navigating bureaucratic systems instilled in Blau a deep interest in how social structures influence individual opportunities and interactions. At Elmhurst, he developed a passion for sociology, inspired by the works of Marx, Durkheim, and Freud. He later pursued his PhD at Columbia University under Robert K. Merton, whose structural functionalism profoundly influenced Blau’s early work. Blau’s academic career included prestigious appointments at the University of Chicago (1953–1970), Columbia University (1970–1988), and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (1988–2000). His intellectual background blended European sociological traditions—particularly Weber’s work on bureaucracy—with the empirical rigor of American sociology, enabling him to cra theories that bridged micro-level interactions with macro-level social structures. Blau’s career was marked by significant accolades, including the presidency of the American Sociological Association in 1973 and membership in the National Academy of Sciences. His personal journey as an immigrant and survivor of political persecution imbued his scholarship with a unique perspective, balancing optimism about democratic institutions with a critical awareness of their limitations.

Blau’s intellectual evolution was driven by a desire to understand how social order emerges from individual interactions and how structures shape opportunities. His early work focused on bureaucracy, challenging Weber’s idealized view by highlighting the efficiency of informal practices within formal organizations. Over time, his interests expanded to social exchange theory and macrostructural frameworks, reflecting his ambition to develop systematic, empirically testable theories. Blau’s ability to integrate insights from psychology, economics, and sociology made his work both theoretically rich and practically applicable, cementing his legacy as a scholar who connected individual agency with societal constraints.

Key Ideas and Concepts

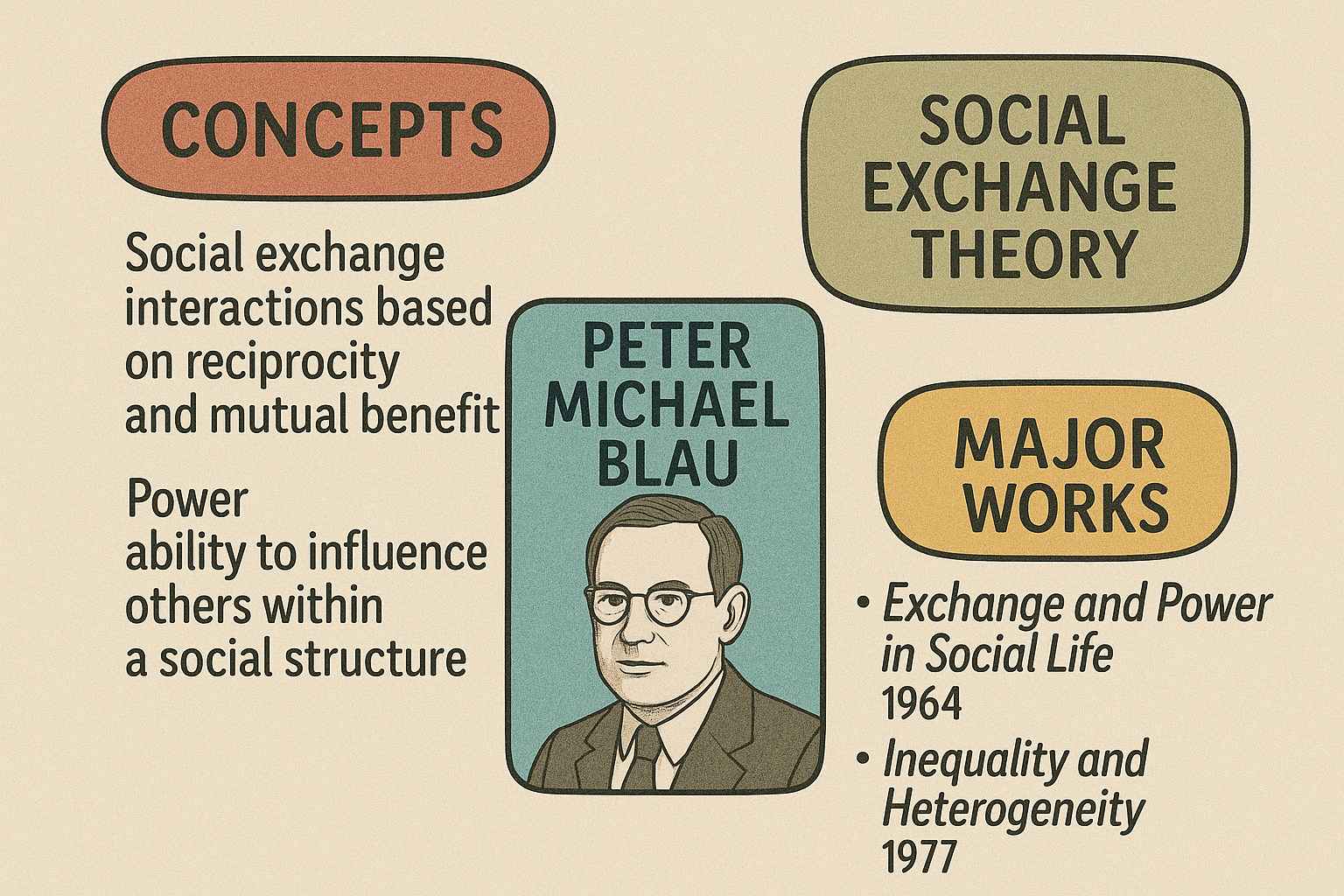

Blau’s sociological contributions are centered on three key areas: social exchange theory, macrostructural theory, and social stratification. His work is distinguished by its effort to link micro-level interactions with macro-level social systems, offering a comprehensive framework for understanding social organization.

Social Exchange Theory: Blau’s most influential contribution is his development of social exchange theory, articulated in his 1964 book Exchange and Power in Social Life. Building on George Homans’ work, Blau expanded the theory by focusing on the structural implications of interpersonal exchanges. He argued that social interactions are driven by the exchange of tangible or intangible rewards—such as status, approval, or resources—with an expectation of reciprocity. Unlike Homans’ psychological focus, Blau incorporated economic principles like supply and demand to explain how power dynamics emerge from unequal exchanges. Power, in Blau’s view, arises when one party controls a valued resource, creating dependency and enabling influence over others. He identified four key processes in social exchange—attraction, competition, differentiation, and integration—that shape interactions and lead to the formation of social structures. These processes explain how trust, loyalty, and authority develop in small groups and how they contribute to larger institutional frameworks. Blau’s theory is notable for its ability to connect individual motivations with emergent social norms and hierarchies.

Macrostructural Theory: In his later work, particularly Inequality and Heterogeneity (1977), Blau developed a macrostructural theory to analyze how social structures emerge from the distribution of populations across social positions. He conceptualized social structure as a multidimensional space defined by “parameters” such as class, race, gender, or occupation. These parameters shape patterns of interaction, with individuals more likely to associate with those in similar positions (a concept akin to homophily). Blau argued that inequality restricts intergroup interactions, while heterogeneity—diversity across parameters—promotes them. His famous quip, “One cannot marry an Eskimo if no Eskimo is around,” illustrates how structural factors like group size or geographic distribution constrain social relations. Unlike his earlier focus on micro-level exchanges, this deductive theory relies on quantitative measures to predict patterns of association without assuming psychological motivations, offering a framework for analyzing large-scale phenomena like integration, discrimination, or social mobility.

Social Stratification and Mobility: Blau’s work on social stratification, notably in The American Occupational Structure (1967), co-authored with Otis Dudley Duncan, transformed the study of social mobility. Using structural equation modeling, the book examined how education, occupation, and parental status influence an individual’s social position. Blau and Duncan’s findings highlighted education as a critical driver of occupational attainment, challenging the notion that social status is primarily inherited. Their work introduced rigorous methodological approaches to studying stratification, influencing subsequent research on inequality. Blau’s optimism about social mobility, informed by his own experience as an immigrant, underscored his belief in the potential of institutions to foster equality, though he acknowledged persistent barriers like racial and economic disparities.

Bureaucracy and Organizations: Blau’s early work focused on organizational sociology, particularly bureaucracy. In The Dynamics of Bureaucracy (1955), he challenged Weber’s view that deviations from formal rules undermine efficiency. Through empirical studies of government agencies, Blau found that informal practices, such as peer consultations, oen enhanced organizational performance. This insight laid the foundation for his later theories by highlighting the interplay between formal structures and informal interactions, a theme that recurs in his work on social exchange and macrostructures.

Major Works

Blau’s scholarship produced several landmark publications that remain foundational in sociology. Below, we explore his major works, which reflect his evolving theoretical interests.

The Dynamics of Bureaucracy (1955): Based on his doctoral research, this book examined two government agencies to explore how bureaucratic structures function in practice. Blau challenged Weber’s idealized model of bureaucracy by demonstrating that informal practices, such as collaboration among workers, often improved efficiency. His findings emphasized the dynamic interplay between formal rules and informal norms, laying the groundwork for his later theories on social exchange and organizational behavior.

Exchange and Power in Social Life (1964): This seminal work introduced Blau’s social exchange theory, a framework for understanding how individual interactions lead to social structures. By integrating economic principles with sociological analysis, Blau explored how power, trust, and norms emerge from reciprocal exchanges. The book’s emphasis on the structural outcomes of micro-level interactions made it a cornerstone of sociological theory, influencing fields like organizational studies and social psychology.

The American Occupational Structure (1967): Co-authored with Otis Dudley Duncan, this book revolutionized the study of social stratification and mobility. Using advanced statistical methods, Blau and Duncan analyzed how factors like education and parental status shape occupational outcomes. Their findings highlighted the role of education in promoting social mobility, offering a model for studying inequality that remains influential in quantitative sociology.

Inequality and Heterogeneity (1977): In this work, Blau introduced his macrostructural theory, focusing on how social structures emerge from the distribution of populations across social positions. By analyzing parameters like class, race, and occupation, Blau provided a deductive framework for understanding patterns of social association, such as intergroup marriage or workplace integration. The book’s quantitative approach and focus on structural constraints marked a significant shift in his scholarship.

Structural Contexts of Opportunities (1994): One of Blau’s later works, this book synthesized his macrostructural theory with his earlier insights on social exchange and stratification. It explored how structural factors shape opportunities for social interaction and mobility, reinforcing Blau’s commitment to understanding the interplay between individual agency and societal constraints.

Critics and Criticisms

Blau’s work, while highly influential, has faced several criticisms. His social exchange theory has been critiqued for its reliance on economic metaphors, which some argue oversimplify the complexity of human relationships. Critics like Richard Emerson contended that Blau’s focus on power and reciprocity neglects altruistic or non-instrumental motivations for social interaction. Similarly, his assumption of rational actors pursuing rewards has been challenged by scholars who emphasize emotional or cultural factors, such as Pierre Bourdieu, who argued for the inclusion of symbolic capital in understanding social dynamics. Blau’s macrostructural theory, while praised for its rigor, has been criticized for its abstract and deductive nature. Critics like Randall Collins argued that it overlooks the role of agency and conflict in shaping social structures, focusing too heavily on statistical patterns. Additionally, some scholars have noted that Blau’s optimism about social mobility, particularly in The American Occupational Structure, underestimates persistent structural barriers like systemic racism or gender inequality, which limit equal access to opportunities. His work on bureaucracy has also faced scrutiny for its limited applicability to non-Western contexts, where informal networks may operate differently due to cultural or historical factors. Despite these criticisms, Blau’s defenders argue that his theories provide a robust framework for analyzing social phenomena across contexts, and his methodological innovations have set a high standard for empirical sociology.

Contemporary Relevance

Blau’s theories remain highly relevant in contemporary sociology, offering tools to analyze pressing social issues. His social exchange theory provides insights into modern phenomena like social media interactions, where likes, shares, and follows function as intangible rewards shaping online relationships and influence. In organizational contexts, his work on bureaucracy informs studies of workplace dynamics, particularly in understanding how informal networks enhance efficiency in rigid corporate or governmental structures. His macrostructural theory is particularly applicable to analyzing globalization and urban diversity, where heterogeneous populations create new patterns of interaction and integration. For example, Blau’s framework can be used to study intergroup relations in multicultural cities or the impact of immigration on social cohesion. His work on social stratification remains crucial for understanding inequality in an era of widening economic gaps and debates over access to education and employment. In the digital age, Blau’s emphasis on structural constraints resonates with discussions of algorithmic bias and unequal access to technology, which shape opportunities for social mobility. Moreover, his interdisciplinary approach—blending sociology, economics, and psychology—offers a model for addressing complex, multifaceted issues like climate change, where individual behaviors and structural policies intersect. While some of Blau’s assumptions, such as rational choice, may require adaptation to account for cultural or emotional factors, his frameworks provide a foundation for analyzing the interplay between individual agency and societal structures in diverse contexts.

References

- Blau, P. M. (1955). The Dynamics of Bureaucracy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

- Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and Power in Social Life. New York: Wiley.

- Blau, P. M., & Duncan, O. D. (1967). The American Occupational Structure. New York: Wiley

- Blau, P. M. (1977). Inequality and Heterogeneity: A Primitive Theory of Social Structure. New York: Free Press.

|

|

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|