Home » Social Thinkers » Karl Polyani

Karl Polyani

Table of Contents

Introduction

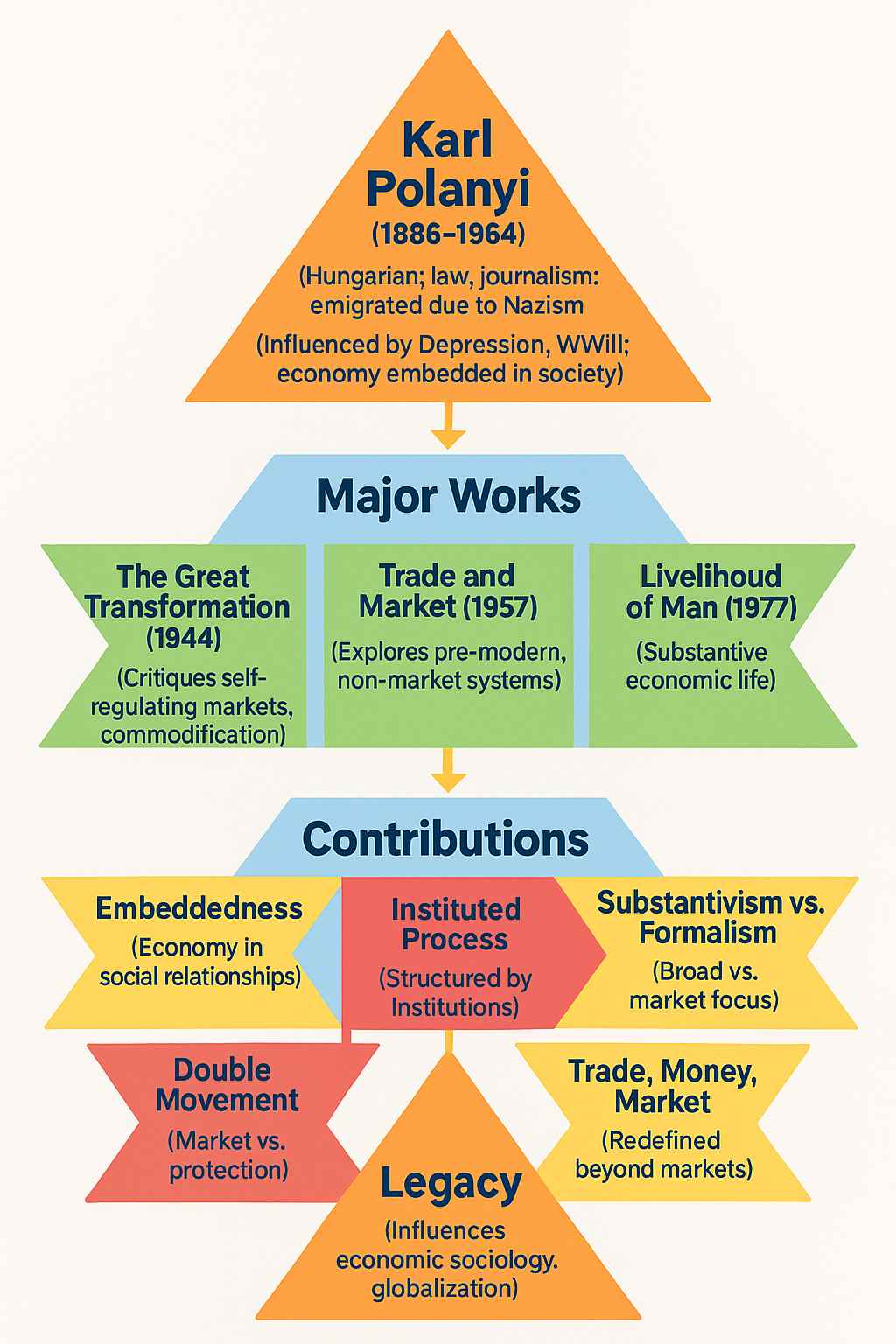

Karl Polanyi (1886–1964) was a Hungarian economic historian, social theorist, and anthropologist whose interdisciplinary work significantly shaped the field of economic sociology. Born in Vienna to a Jewish family, Polanyi initially pursued a career in law and journalism before emigrating to England and later the United States due to political upheavals, including the rise of Nazism. His intellectual journey was marked by a deep engagement with the social implications of economic systems, influenced by his experiences during the Great Depression and World War II. Polanyi’s scholarship bridged economics, sociology, and anthropology, challenging the dominant neoclassical economic paradigms of his time. His central thesis—that the economy is deeply embedded in social structures and cannot be understood in isolation—laid the foundation for a substantivist approach to economic analysis. This perspective has had a lasting impact on sociological thought, particularly in understanding the interplay between markets, society, and institutions.

Major Works of Karl Polanyi

Polanyi’s contributions are most prominently articulated in his seminal works, which reflect his commitment to historical and comparative analysis:

- The Great Transformation (1944): This book is Polanyi’s magnum opus, where he examines the emergence of market economies in the 19th century and their social consequences. He critiques the self-regulating market as a utopian construct, arguing that it disrupts social fabric through the commodification of land, labor, and money

- Trade and Market in the Early Empires (1957): Co-edited with others, this work explores pre-modern economic systems, emphasizing non-market forms of trade and exchange. It expands on his substantivist framework by analyzing ancient economies through a sociological lens.

- The Livelihood of Man (1977): Published posthumously, this collection of essays further develops Polanyi’s ideas on the substantive meaning of economic life, focusing on how human livelihood is shaped by social and environmental interactions rather than market mechanisms alone.

Contribution to Sociology

The Concept of Embeddedness

One of Polanyi’s most enduring contributions to sociology is the concept of embeddedness, which posits that economic activities are not autonomous but are deeply integrated into social relationships and institutions. In pre-modern societies, economic life was governed by reciprocity and redistribution, contrasting with the market-driven exchange dominant in modern capitalism. This idea challenges the formalist view that economics can be reduced to individual rational choices based on scarcity. By emphasizing embeddedness, Polanyi provided sociologists with a framework to analyze how cultural norms, kinship, and political structures shape economic behavior, influencing studies of globalization and social inequality.

Economy as an Instituted Process

Polanyi’s notion of the economy as an instituted process is a cornerstone of his sociological contribution. He argued that economic activities—production, distribution, and consumption—are not random but are structured by social institutions that lend them unity and stability. This process involves two dimensions: “process” (movement and appropriation of goods) and “institutedness” (the institutional framework that sustains these activities). By categorizing goods into higher-order (manufacturer’s goods) and lower-order (consumer goods) and analyzing locational and appropriational movements, Polanyi offered a dynamic model of economic life. This perspective has enriched sociological analyses of institutional change and economic organization.

The Double Movement

In The Great Transformation, Polanyi introduced the concept of the double movement, describing the tension between the expansion of market forces and society’s protective responses. As markets commodify land, labor, and money—termed “fictitious commodities”—they threaten social cohesion, prompting state and societal interventions such as labor laws and welfare systems. This dialectical process highlights the interplay between economic liberalism and social protection, a theme that resonates in contemporary sociological debates on neoliberalism and social policy. Polanyi’s analysis provides a lens to understand how economic systems evolve within social contexts.

Substantivism vs. Formalism

Polanyi’s distinction between substantivist and formalist approaches to economics is a critical contribution to sociological theory. The formalist view, rooted in neoclassical economics, focuses on rational choice and scarcity within market systems, primarily applicable to Western contexts. In contrast, the substantivist approach, which Polanyi championed, defines the economy as the process by which humans interact with their social and physical environments to satisfy material needs. This broader perspective allows sociologists to study diverse economic systems—ancient, non-market, and modern—beyond the confines of price-making markets, influencing comparative sociological research.

Three Forms of Integration: Reciprocity, Redistribution, and Exchange

Polanyi identified three forms of economic integration—reciprocity, redistribution, and exchange—as alternative mechanisms through which economies are stabilized and unified within society. Reciprocity involves symmetrical exchanges between social groups, oen supported by customs like gi-giving. Redistribution entails the centralized collection and allocation of goods, as seen in state or household systems. Exchange, reliant on market mechanisms, involves mutual appropriation at fixed or bargained prices. These forms are not developmental stages but coexisting patterns, requiring specific institutional support (e.g., symmetrical groupings for reciprocity, centrality for redistribution). This typology has enriched sociological understandings of economic diversity and institutional interdependence.

Reconceptualization of Trade, Money, and Market

Polanyi’s substantivist redefinition of trade, money, and markets challenges their formalist interpretations. Trade, beyond market exchange, includes gi trade (ceremonial reciprocity), administrative trade (treaty-based), and market trade (price-driven), each with distinct personnel, goods, and two-sidedness. Money, in substantivist terms, serves payments, accounting, and exchange, oen as special-purpose objects in non-market contexts, contrasting with its formal role as a market medium. Markets, rather than mere exchange loci, are institutions shaped by supply/demand crowds, exchange rates, and competition, with historical variations like separate auctions in ancient societies. These reconceptualizations have informed sociological studies of economic institutions and their evolution

Influence and Legacy in Sociology

Polanyi’s ideas have profoundly influenced economic sociology, institutional analysis, and globalization studies. His embeddedness concept is a foundational idea in the “new economic sociology,” inspiring scholars like Mark Granovetter to explore network-based economic behavior. The double movement framework informs analyses of neoliberal policies and social resistance, while his substantivist approach supports comparative studies of non-Western economies. Polanyi’s emphasis on historical specificity and institutional context has also shaped anthropological sociology, encouraging interdisciplinary research. His legacy endures in debates on sustainability, inequality, and the social limits of markets, making him a pivotal figure in 20th-century social theory.

References

- Polanyi, K. (1944). The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Polanyi, K., Arensberg, C. M., & Pearson, H. W. (Eds.). (1957). Trade and Market in the Early Empires: Economies in History and Theory. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

- Polanyi, K. (1977). The Livelihood of Man (Edited by H. W. Pearson). New York: Academic Press.

|

|

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|