Rural Sociology

Index

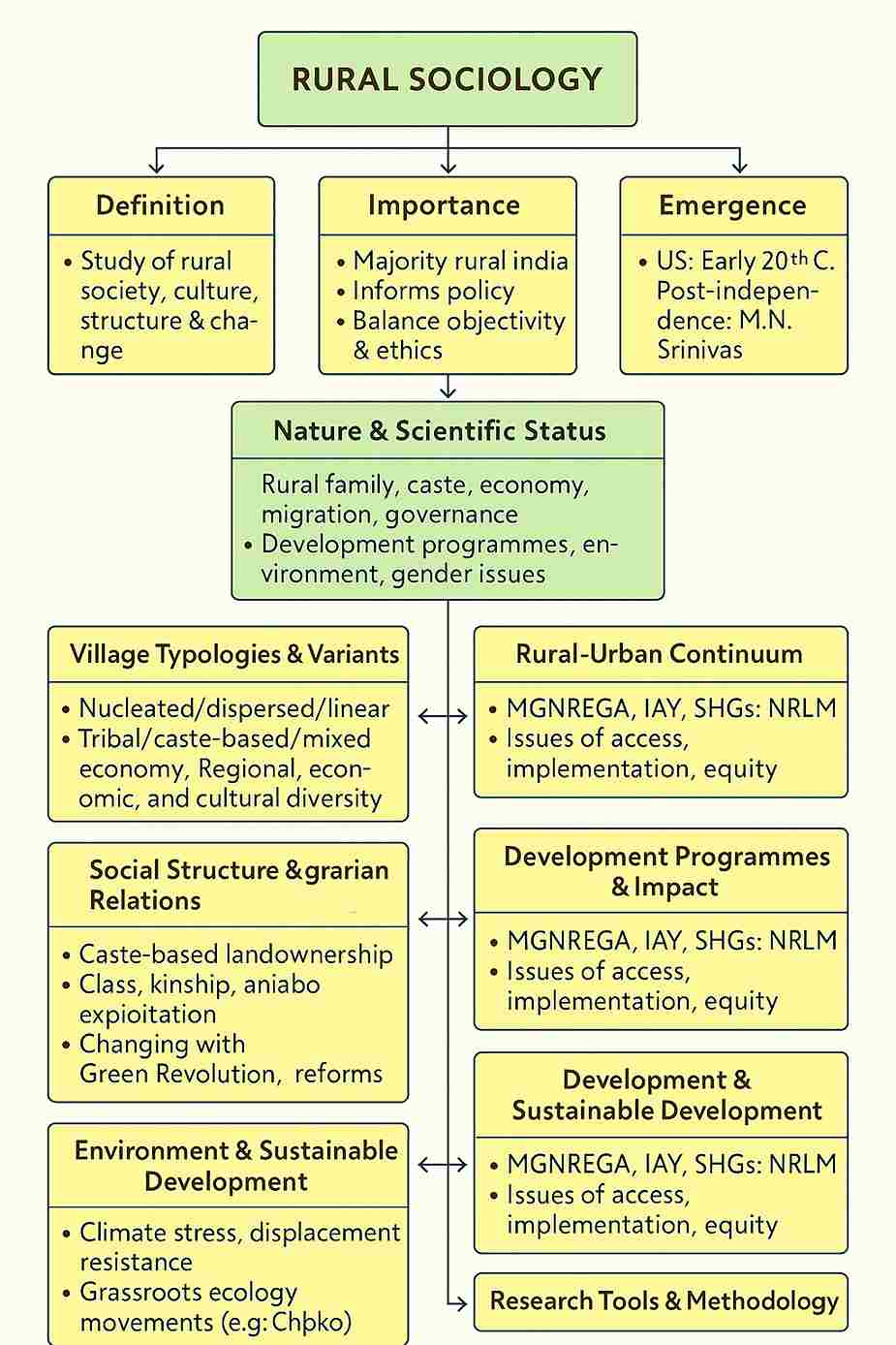

- Introduction to Rural Sociology

- Historical Evolution and Emergence of Rural Sociology

- Importance and Relevance of Rural Sociology in Contemporary Society

- Nature of Rural Sociology: Scientific and Interpretive Dimensions

- Scope of Rural Sociology: Interdisciplinary and Expansive

- The Village Community: Social Universe of Rural Sociology

- Typologies and Classification of Village Communities

- Rural-Urban Continuum: Beyond the Binary

- Rural Social Structure: Caste, Class, and Kinship in Agrarian Contexts

- Agrarian Relations and the Political Economy of Rural Life

- Peasant Movements: Resistance, Mobilization, and Change

- Panchayati Raj and Rural Governance

- Rural Development Programmes: Critical Assessment

- Self-Help Groups (SHGs) and Rural Women’s Empowerment

- Environmental Concerns and Sustainable Rural Development

- Tools, Techniques, and Methodologies in Rural Sociological Research

- Conclusion

Introduction to Rural Sociology

Rural sociology is the academic discipline that engages with the study of rural social structures, processes, institutions, and change. Unlike general sociology, which analyzes society at large, rural sociology narrows its focus to the intricate tapestry of village life—its culture, livelihood patterns, kinship arrangements, caste networks, and modes of production. This eld emerges as crucial in the Indian context where the village has historically been the locus of civilizational continuity and economic activity. Indian rural society embodies a rich blend of tradition and transformation; understanding its dynamics is vital for developmental planning, governance, and social justice. Rural sociology not only seeks to describe and document these dynamics but also aims to interpret their causes, implications, and trajectories over time. Moreover, the discipline serves a dual function: academically, it deepens sociological inquiry through context-specific research; practically, it informs policies that target rural poverty, inequality, and underdevelopment. Thus, rural sociology stands at the intersection of theory and praxis, tradition and modernity, and locality and globalization.

Historical Evolution and Emergence of Rural Sociology

The birth of rural sociology can be traced to early 20th-century America, rooted in the need to systematically understand rural disintegration caused by urbanization, industrialization, and agricultural crises. The establishment of the American Country Life Commission in 1908 and the later endorsement by the American Sociological Society laid the groundwork for formal recognition. The discipline matured with the creation of dedicated journals like Rural Sociology in 1936 and the Rural Sociological Society in 1937. In India, rural sociology took shape during the colonial period but was largely embedded within administrative concerns. Pioneers like Sir Henry Maine adopted a legalistic and Eurocentric approach, portraying Indian villages as static and self-sufficient, an idea later challenged by scholars like Louis Dumont and D.N. Majumdar, who highlighted the integrative role of caste and kinship. Post-independence, the discipline ourished with the efforts of Indian sociologists such as M.N. Srinivas, S.C. Dube, and A.R. Desai, who shifted focus from static models to dynamic processes of change—especially those driven by state-led development, agrarian restructuring, and political mobilization. Rural sociology in India, thus, emerged not merely as an academic curiosity but as a response to the practical exigencies of nation-building in a predominantly agrarian society.

Importance and Relevance of Rural Sociology in Contemporary Society

The significance of rural sociology lies in its capacity to illuminate the deep-rooted and complex social realities that prevail in the countryside—realities often ignored or misrepresented in mainstream academic discourse and policymaking. In India, where over two-thirds of the population is rural, and agriculture employs the majority, the discipline oers a vital framework for understanding the interplay between tradition and development, caste and class, patriarchy and agency, and local governance and state intervention. It highlights how poverty, landlessness, ecological degradation, and caste-based exclusion are not isolated problems but interconnected processes rooted in structural inequalities. Rural sociology also examines how globalization, migration, and technological penetration are reshaping the aspirations, social norms, and livelihoods of rural people. In doing so, it bridges the epistemological gap between empirical eld realities and theoretical abstractions. More importantly, it serves as a diagnostic tool for identifying the successes and failures of rural development programmes, enabling evidence-based interventions. It contributes to social audits, impact assessments, and participatory planning, ensuring that the voice of the rural poor is not only heard but also valued in policymaking. In an age of climate crisis and uneven development, rural sociology’s insights into resilience, sustainable practices, and community solidarity are more urgent than ever.

Nature of Rural Sociology: Scientific and Interpretive Dimensions

Rural sociology blends positivist rigor with interpretive nuance, making it both a science and an art of understanding rural life. As a social science, it applies systematic methods of data collection, hypothesis testing, and generalization. It employs quantitative tools like large-scale surveys, censuses, and econometric analysis to track patterns in income, landholding, literacy, health, and mobility. Simultaneously, it relies on qualitative techniques such as ethnography, participant observation, and oral histories to capture the cultural and emotional dimensions of rural existence. What makes rural sociology distinctive is its contextual sensibility—it does not seek universal laws but aims to understand how structures like caste, patriarchy, religion, and agrarian relations shape and are shaped by the local environment. Some scholars argue that the discipline lacks scientific objectivity due to the moral and political implications of its findings—especially when it challenges land elites, developmental models, or state narratives. However, this engaged scholarship is its strength, not weakness. Rural sociology recognizes that neutrality is not the same as objectivity, and that understanding rural life demands ethical responsibility, cultural empathy, and historical depth. It is, therefore, a profoundly human science—rigorous, reflective, and responsive to the lived realities of rural populations.

Scope of Rural Sociology: Interdisciplinary and Expansive

The scope of rural sociology is impressively broad, encompassing various dimensions of village life—from kinship to climate change, from caste to communication technologies. It investigates core institutions such as family, caste, religion, and the agrarian economy, while also exploring contemporary phenomena like rural-urban migration, gender empowerment, digital divide, and environmental justice. Its interdisciplinary nature allows it to borrow tools and perspectives from anthropology, economics, political science, and ecology. For instance, in studying rural indebtedness, it may combine economic data with ethnographic narratives; in analyzing caste conflict, it may use both historical archives and real-time eld observations. The scope also includes evaluation of rural development programmes such as MGNREGA, the National Rural Health Mission, or Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana, by assessing their social impact and implementation gaps. Furthermore, rural sociology examines political participation in Panchayati Raj Institutions, the role of Self-Help Groups in women’s empowerment, and the impact of agribusiness on small farmers. With globalization altering consumption patterns, occupational aspirations, and land use in villages, the scope of rural sociology continues to expand to accommodate these dynamic shifts. It acts as a mirror reflecting both the continuities and contradictions of rural India.

The Village Community: Social Universe of Rural Sociology

The village community forms the nucleus of rural sociological analysis. Far from being an isolated unit, the village is a microcosm of larger societal processes—hierarchies, solidarities, resistances, and negotiations. Villages in India are often marked by strong social cohesion, stable kinship networks, shared religious rituals, and informal social control through customs and elders’ authority. However, they are also sites of inequality—particularly with respect to caste, gender, and access to resources. The traditional village was often portrayed as self-sufficient, bound by the jajmani system of inter-caste service exchange, and regulated by the Panchayat. However, modern research shows that villages have always been embedded in larger political economies, subject to land taxes, famines, state control, and market influences. Today’s villages are more mobile, aspirational, and politically active than ever before. Education, migration, mass media, and social movements have transformed village life, introducing new forms of mobility and consciousness. Yet, certain older patterns—such as caste-based violence, patriarchy, and economic dependence on agriculture—still persist, sometimes even reasserting themselves in new guises. Understanding this complex mosaic of change and continuity is essential for any meaningful engagement with rural India, and it is here that rural sociology proves its intellectual worth.

Typologies and Classification of Village Communities

Understanding rural society requires recognizing its internal diversity, and rural sociology offers several typologies to classify village communities. Villages differ not only in size and geography but also in social composition, economic activity, and institutional organization. Based on settlement patterns, villages may be nucleated (clustered houses), linear (along roads or rivers), or dispersed (scattered homes). These spatial patterns influence social interaction, land use, and access to services. Socially, villages may be homogeneous, where most inhabitants belong to the same caste or tribe, or heterogeneous, marked by multiple castes with hierarchical relations. Economically, some villages are agriculturally dominant, while others have diversified into artisanal work, wage labor, or rural industry. The presence or absence of irrigation facilities, road connectivity, schools, and markets further distinguishes prosperous villages from marginalized ones. Typologies also exist based on administrative roles—such as revenue villages, Gram Panchayat headquarters, or model villages under government schemes. Recognizing these differences is crucial for targeted policy interventions, as what works for a tribal hamlet may not suit a peri-urban, commercially oriented village. Hence, typologies are not mere academic exercises but essential tools for developmental governance.

Rural-Urban Continuum: Beyond the Binary

One of the significant conceptual contributions of rural sociology is the idea of the rural-urban continuum. Traditional sociology tended to portray rural and urban life as binaries—rural as static, communal, and simple; urban as dynamic, individualistic, and complex. However, this binary overlooks the hybrid realities that exist on the margins of cities and in villages influenced by urbanization. The rural-urban continuum recognizes that these categories are not mutually exclusive but lie on a spectrum with overlapping features. For instance, a village near a city may retain agricultural practices while simultaneously engaging in wage labor, digital transactions, and consumer culture. Similarly, small towns may exhibit caste rigidity, community ties, and informal governance mechanisms typically associated with villages. This concept is especially relevant in India, where economic liberalization, infrastructural expansion, and digital penetration have created new spaces of transition—peri-urban areas, census towns, and rural industrial clusters. These spaces defy traditional categories and demand new methodological tools for analysis. The rural-urban continuum helps scholars and policymakers navigate this uid landscape, allowing for more nuanced, flexible, and inclusive approaches to both research and development.

Rural Social Structure: Caste, Class, and Kinship in Agrarian Contexts

The social structure of rural India is marked by a complex interweaving of caste, class, kinship, and community ties. Among these, the caste system historically served as the organizing principle of social hierarchy, occupational roles, and everyday life in villages. It not only determined access to resources and services but also dictated social behavior, marriage alliances, and religious obligations. The caste-based division of labor ensured the economic interdependence of communities, but also sustained inequality and exclusion—particularly of Dalits and other marginalized castes. Land ownership patterns often mirror caste hierarchies, leading to the overlap between caste and class, where upper castes control productive resources and lower castes remain landless laborers or marginal farmers. However, the picture is not entirely static. Agrarian reforms, political mobilization through parties and unions, reservation policies, and education have challenged traditional hierarchies. Kinship, particularly in the form of extended joint families and lineage-based groups (gotras), continues to play a critical role in social regulation and support. Yet, with rising mobility, urban exposure, and nuclear family trends, rural social structure is undergoing transformation. Rural sociology critically analyzes this interplay of continuity and change, mapping the emergence of new social classes, caste dynamics, and forms of kinship solidarity or fragmentation in the contemporary village.

Agrarian Relations and the Political Economy of Rural Life

The agrarian structure in rural India reflects deep-rooted inequalities arising from historical patterns of land distribution, colonial land revenue systems, and post-colonial policies. At the heart of this structure lies the relationship between landowners, tenants, sharecroppers, and landless laborers. Despite land reform legislations, much of rural India continues to experience skewed land ownership, absentee landlordism, and exploitative tenancy systems. The Green Revolution, while increasing agricultural productivity in certain regions, exacerbated regional disparities and strengthened the economic position of large landholders, leading to the rise of a rural bourgeoisie. This new class, often drawn from dominant castes, began to assert political power through Panchayats, cooperatives, and agrarian lobbies. Conversely, marginal and small farmers, many from backward castes or tribal groups, were pushed further to the margins. These inequities gave rise to a range of agrarian movements, from class-based revolts like the Naxalite movement to issue-based struggles around minimum support prices, irrigation rights, or debt waivers. Rural sociology examines these movements not only as reactions to exploitation but also as expressions of rural agency, resistance, and demands for alternative development models. The discipline investigates how the agrarian question remains central to India’s democratic and developmental trajectory.

Peasant Movements: Resistance, Mobilization, and Change

Peasant movements form an integral component of rural sociological inquiry, especially in understanding the politics of protest and resistance. These movements challenge the dominant narratives of passive peasantry and demonstrate that rural populations are capable of collective action to demand rights, justice, and dignity. From the Tebhaga movement in Bengal and the Telangana armed struggle to the more recent nationwide farmers’ protests against farm laws, these movements highlight how economic distress, ecological vulnerability, and political exclusion can galvanize large-scale rural mobilization. Scholars like A.R. Desai and D.N. Dhanagare have shown how peasant movements are not just economic in nature but are deeply embedded in the social and cultural fabric of rural life. Rural sociology analyzes the leadership patterns of these movements, their class composition, ideological orientations, and relationships with political parties, NGOs, and media. It also studies their outcomes—not just in terms of immediate policy changes but also in transforming rural consciousness, redening citizenship, and opening new avenues for participatory governance. In this sense, peasant movements are both symptoms of agrarian distress and catalysts of social transformation.

Panchayati Raj and Rural Governance

The 73rd Constitutional Amendment Act (1992) marked a turning point in Indian rural governance by institutionalizing Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs) as the third tier of democratic governance. With provisions for decentralization, reservation for women and marginalized communities, and periodic elections, PRIs were envisioned as vehicles for participatory development and grassroots democracy. Rural sociology plays a critical role in analyzing how Panchayats operate in practice—who participates, who dominates, and whose voices are excluded. Studies have shown that while PRIs have empowered sections of society, especially women and Dalits, they have also been captured by dominant castes and local elites in many regions. The intersection of caste, gender, and political patronage often determines the functioning of Panchayats. Moreover, the gap between legal mandates and actual devolution of powers continues to limit the transformative potential of PRIs. Rural sociologists assess not only the institutional design of Panchayats but also their social embeddedness—the networks, norms, and power relations that shape their functioning. In doing so, they contribute to debates on decentralization, governance reforms, and inclusive development.

Rural Development Programmes: Critical Assessment

Development programmes form the policy backbone for improving rural livelihoods, infrastructure, education, and health. Initiatives like the Indira Awas Yojana (IAY) for housing, Swarnjayanti Gram Swarozgar Yojana (SGSY) for self-employment, and Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) for wage employment have sought to address rural poverty and unemployment. While these schemes represent significant state interventions, rural sociology emphasizes the importance of examining their social and institutional dynamics. Who benefits from these programmes? Are the poor really empowered, or are resources captured by local elites? How does gender affect access to benets? How do caste hierarchies mediate entitlement and delivery? These are the questions rural sociologists pursue through eld studies and impact assessments. They also analyze how schemes are implemented, the role of intermediaries, the effectiveness of grievance redressal mechanisms, and the degree of community participation. Beyond technical efficiency, the success of rural development depends on social equity, accountability, and responsiveness—all of which are central to the sociological lens.

Self-Help Groups (SHGs) and Rural Women’s Empowerment

The emergence of Self-Help Groups (SHGs) has added a new dimension to rural development by combining financial inclusion with collective empowerment. SHGs typically comprise 10–20 women who pool savings, access microcredit, and undertake income-generating activities. Supported by government schemes, NGOs, and banks, SHGs aim to enhance women’s agency, promote financial literacy, and create social capital. Rural sociology explores how SHGs function as both economic and social institutions. On the economic front, they provide access to credit, markets, and skills. On the social front, they create platforms for solidarity, dialogue, and collective action. Women involved in SHGs often report increased mobility, voice in family decisions, and confidence in public settings. However, the success of SHGs is not uniform—contextual factors like caste exclusion, patriarchal resistance, market access, and institutional support play a significant role. Rural sociologists document both the successes and the limitations of SHGs, providing insights into how grassroots institutions can drive gender-sensitive rural development. They also caution against over-romanticizing these groups, advocating for structural support and policy integration to ensure sustainable impact

Environmental Concerns and Sustainable Rural Development

In recent decades, the environmental dimension of rural life has come into sharp focus, particularly in the wake of deforestation, water scarcity, climate change, and ecological degradation. Villages, often located in ecologically fragile zones, are disproportionately affected by these changes, which threaten their agrarian livelihoods and survival. The construction of large dams, mining projects, and industrial corridors frequently leads to displacement, loss of commons, and ecological stress. Rural sociology approaches environmental issues not just as technical problems but as socio-political concerns. It analyzes how development-induced displacement affects vulnerable communities, how local knowledge systems oer sustainable alternatives, and how grassroots movements like the Chipko or Narmada Bachao Andolan articulate environmental justice. The concept of sustainable development—often dened in top-down terms—is critically examined through the lived experiences of rural populations. Questions of access, equity, and participation are central: Who decides what counts as development? Who bears the cost of ecological damage? Rural sociology offers a nuanced framework to answer these questions, combining ecological awareness with social justice.

Tools, Techniques, and Methodologies in Rural Sociological Research

Methodologically, rural sociology has evolved a rich repertoire of tools to capture the complexity of rural life. These include household surveys, participant observation, structured and unstructured interviews, focus group discussions, case studies, life histories, and village monographs. Surveys help in collecting quantitative data on indicators like landholding, income, literacy, and health. Ethnographic methods allow for an in-depth understanding of rituals, kinship, power dynamics, and everyday practices. Tools like participatory rural appraisal (PRA) engage villagers directly in mapping resources, needs, and priorities. Importantly, rural sociology emphasizes ethical reflexivity—researchers must respect local customs, minimize extractive practices, and ensure informed consent. It also values triangulation, i.e., using multiple methods to cross-verify findings. Increasingly, digital tools—such as mobile data collection apps, GIS mapping, and social media ethnography—are being integrated into rural research. Yet, the heart of rural sociological inquiry remains the eld—a site where the abstract meets the everyday, where theory meets testimony, and where knowledge is co-produced with rural actors.

Conclusion

Rural sociology remains one of the most dynamic and socially engaged branches of sociology, especially in a country like India, where rural transformations are central to national development. Far from being an obsolete study of tradition-bound villages, it is a forward-looking discipline that examines how rural societies respond to change, negotiate development, and assert their rights. It addresses some of the most pressing questions of our time: How do we ensure food security, ecological balance, gender justice, and participatory governance in rural areas? How do we reconcile economic growth with rural livelihoods? How do we listen to rural voices in policymaking? Through its grounded, interdisciplinary, and critical approach, rural sociology does not merely observe rural society—it participates in its transformation. As such, it is not just a eld of study but a eld of solidarity, ethics, and democratic imagination.

References

- Desai, A.R. (Ed.). Rural Sociology in India. Popular Prakashan

- Dube, S.C. India’s Changing Village. Routledge.

- Dhanagare, D.N. Peasant Movements in India, 1920-1950. Oxford University Press.

- Bertrand, A.L. Rural Sociology: An Analysis of Contemporary Rural Life. McGraw-Hill.

- Dube, S.C. Contemporary India and Its Modernization. Vikas Publishing

- Dumont, L. Homo Hierarchicus: The Caste System and Its Implications. University of Chicago Press.

Rural life is the principal pivot around which whole Indian social life revolves. India is a land of agriculture. Its history, customs and traditions, complex social organization and unity in diversity etc can be understood by the study of rural life.

Rural sociology is the scientific study of rural society. It involves a systematic study of rural society, its institutions, activities, interactions and social change. It not only deals with the social relationships of man in a rural environment but also takes urban surroundings into consideration for a comparative study.

According to A.R Desai rural sociology should be to make a systematic, scientific and comprehensive study of the rural social organization of its structure, function and objective tendencies of development and on the basis of such a study to discover the laws of its development.

T.L Smith says that some investigators study social phenomena that are present only in or largely confined to the rural environment to persons engaged in agricultural occupation.

Such sociological aspects and principles as one derived from the study of rural social relationships may be referred to as rural sociology. Bertrand has observed that in the broadest definition rural sociology is the study of human relationships in rural environment.

Rural sociology is a holistic study of rural social setting. It provides us with valuable knowledge about the rural social phenomena and social problems which helps us in understanding rural society and making prescriptions for its all round progress and prosperity.

|

|

- Origin and development of Rural Sociology

- The Indian Context of Rural Sociology

- Main features of Rural Society

- Caste Structure In Rural Set Up

- Role of caste in Rural Society

- Jajmani System in Rural Society

- Agrarian changes after Independence in Rural Society

- Land Reforms in Rural Society

- Community Development Programme in Rural Society

- Green Revolution

- Cooperatives In India

- Village Community in India

- The Methods in the study of Rural Sociology

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|