Home » Social Thinkers » Radcliffe Brown

Radcliffe Brown

Index

1. Introduction

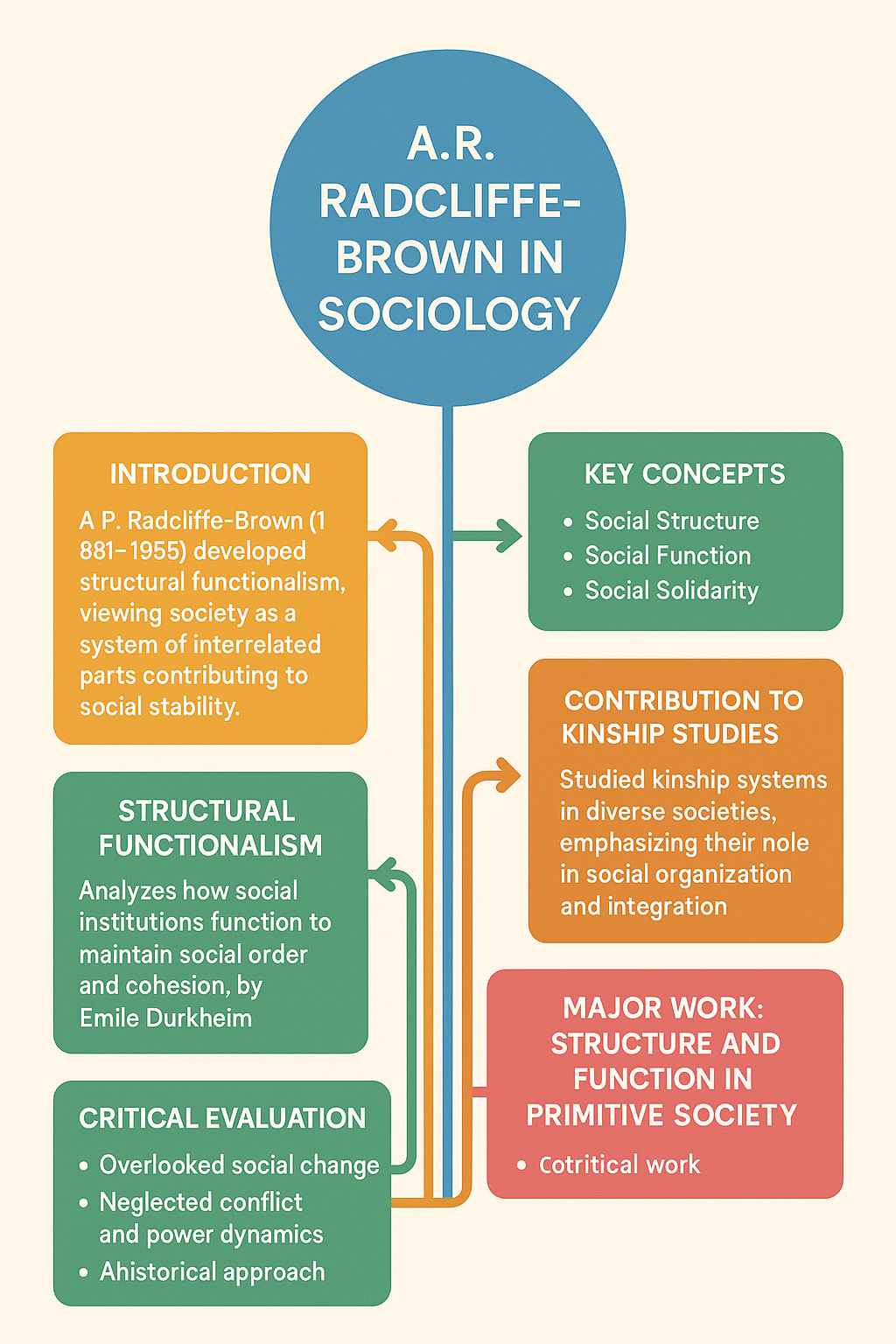

A.R. Radcliffe-Brown (1881–1955) is recognized as one of the central figures in the development of modern social anthropology and a significant contributor to the field of sociology. His academic career was distinguished by his effort to move anthropology away from speculative cultural evolutionism and towards a more scientific and empirical approach to the study of human societies. Drawing heavily from the work of Émile Durkheim, Radcliffe-Brown sought to establish anthropology—and by extension, sociology—as a natural science of society that could identify the laws governing social organization. Through fieldwork in the Andaman Islands, Africa, and Australia, he built a strong foundation for what would later be termed “structural functionalism.” This framework emphasized the interdependence of institutions and their role in maintaining the cohesion and continuity of society. Radcliffe-Brown’s ideas laid the groundwork for subsequent developments in sociological theory, particularly in the areas of kinship, legal systems, social norms, and collective values.

2. Structural Functionalism: The Core Framework

Radcliffe-Brown’s structural functionalism emerged as a coherent theoretical framework aimed at understanding how societies maintain stability and coherence through interrelated institutional structures. He conceptualized society as an organism in which each part—be it a ritual, kinship norm, legal custom, or political institution—performed a necessary function that contributed to the overall health and maintenance of the social system. Unlike Malinowski, who focused on how institutions satisfied individual psychological needs, Radcliffe-Brown insisted that the function of any institution should be assessed in terms of its contribution to the survival of the social structure itself. He drew inspiration from biology and emphasized the idea of social integration, wherein institutions exist not in isolation but as part of a mutually dependent whole. This meant that the analysis of any cultural practice should consider how it maintains the structural equilibrium of society. Radcliffe-Brown believed that scientific anthropology, much like the natural sciences, should be based on the discovery of general laws through comparative empirical research. He thus promoted cross-cultural analysis, looking for universal principles that governed social life across different societies.

3. Key Concepts in Radcliffe-Brown’s Sociology

Central to Radcliffe-Brown’s sociology is the idea of “social structure,” which he defined as the actual pattern of social relationships among individuals and groups, rather than abstract or ideal types. These relationships are both observable and enduring, forming the backbone of social organization. A related idea is that of “social function,” which refers to the role a particular institution or practice plays in maintaining the structure of society. For Radcliffe-Brown, the function of a practice was not measured by its utility for an individual but by its contribution to the cohesion and continuity of the social order. The concept of “social solidarity” also played a pivotal role in his work, echoing Durkheim’s emphasis on collective consciousness. In this framework, rituals, norms, and customs are seen as mechanisms that reproduce shared values and integrate individuals into a collective. Another notable concept is the differentiation between “structure” and “organization.” Structure refers to the enduring pattern of social relationships, whereas organization refers to the specific arrangements and activities within those structural roles. This distinction allowed Radcliffe-Brown to analyze the dynamic interplay between social norms and lived social practice without reducing one to the other.

4. Kinship and Social Organization

One of Radcliffe-Brown’s most influential contributions to both anthropology and sociology lies in his systematic study of kinship, particularly in African societies. His 1950 edited volume African Systems of Kinship and Marriage brought together a wide range of ethnographic data, unified by a structural-functionalist framework. He approached kinship not as a set of biological facts but as a system of social relationships grounded in culturally defined genealogical connections. For Radcliffe-Brown, kinship served as the primary organizing principle in stateless societies, binding individuals into cohesive social groups through networks of rights, duties, and obligations. He introduced the idea of the “unity of the sibling group” as a fundamental organizing principle in many patrilineal societies, highlighting how brothers shared not only property and ritual obligations but also political functions. Marriage, in his view, was less a personal union and more a social arrangement that linked families and lineages, ensuring the legitimacy of offspring and the continuity of alliances. He famously redefined marriage as a mechanism through which a child gains legitimate social parenthood, thereby framing reproduction as a structural rather than individual matter.

Radcliffe-Brown also provided groundbreaking insights into the social functions of institutionalized behavioral norms such as joking and avoidance relationships. Joking relationships, which allow for controlled expressions of hostility or familiarity between specific categories of relatives, were seen as mechanisms for managing potential tensions and preserving group harmony. Avoidance relationships, such as those between a son-in-law and mother-in-law, similarly function to regulate interactions in potentially stressful or ambiguous relational spaces. His attention to such patterns demonstrated how even informal and affective behaviors were structured by social norms that served the greater need for social stability.

5. Major Work: Structure and Function in Primitive Society

Radcliffe-Brown’s most influential theoretical contributions are consolidated in his seminal book Structure and Function in Primitive Society (1952). This collection of essays outlines his mature vision of a scientific sociology grounded in structural functionalism. The core proposition of the book is that institutions must be studied in terms of how they contribute to maintaining the balance and integration of the social system. He argued that cultural practices such as kinship terminology, legal sanctions, religious rituals, and economic customs are all responses to universal needs for social cohesion and order. For example, in his discussion of totemism, Radcliffe-Brown rejected psychological or evolutionary explanations and instead emphasized how totemic systems reinforce group identity and internal solidarity. Similarly, his analysis of ritual underscored its role in renewing social bonds and expressing collective values. He distinguished between formal (organized) and informal (diffuse) sanctions as mechanisms of social control, showing how societies lacking centralized authority still maintained order through reciprocal obligations and moral norms. His method combined rigorous ethnographic observation with a comparative search for social laws, marking a significant step in the professionalization of both anthropology and sociology.

6. Critiques and Limitations

While Radcliffe-Brown’s work laid a robust foundation for structural analysis in the social sciences, it has also faced significant criticism. His theoretical focus on stability, cohesion, and equilibrium led him to overlook conflict, change, and power dynamics. Critics argue that his reliance on an organic analogy—viewing society as a well-functioning body—rendered him blind to the inherent inequalities and struggles that exist within social systems. His approach tended to portray institutions as natural and necessary, rather than as historical constructs open to contestation and transformation. Moreover, by emphasizing synchronic analysis (studying societies at a single point in time), he neglected historical processes and the role of individual agency in shaping social life. Feminist anthropologists and political economists have particularly criticized his functionalist assumptions for downplaying gendered hierarchies, economic exploitation, and colonial contexts. Nevertheless, even his critics acknowledge the systematic rigor and comparative clarity his work introduced to the study of society.

7. Legacy and Influence on Sociology

Despite its limitations, Radcliffe-Brown’s work remains foundational in the history of sociology. His structural-functional framework influenced not only anthropologists but also major sociological theorists like Talcott Parsons, who adapted the idea of social systems and functional prerequisites into his general theory of action. Radcliffe-Brown’s emphasis on empirical observation, structural relationships, and systemic analysis helped shape sociological subfields such as kinship studies, legal sociology, and the sociology of religion. His work also paved the way for later theoretical developments such as structuralism and system theory, and many of the analytical terms he coined—like “corporate group,” “social structure,” and “segmentary lineage”—remain integral to sociological vocabulary. More broadly, his insistence on treating social life as subject to patterned regularities and capable of systematic analysis continues to inform the methodological ambitions of sociology today.

8. References

- Radcliffe-Brown, A.R. (1922). The Andaman Islanders. Cambridge University Press.

- Radcliffe-Brown, A.R. (1950). African Systems of Kinship and Marriage (Ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Radcliffe-Brown, A.R. (1952). Structure and Function in Primitive Society. Free Press.

|

|

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|