Home » Social Thinkers » Karl Mannheim

Karl Mannheim

Index

Introduction and Intellectual Background

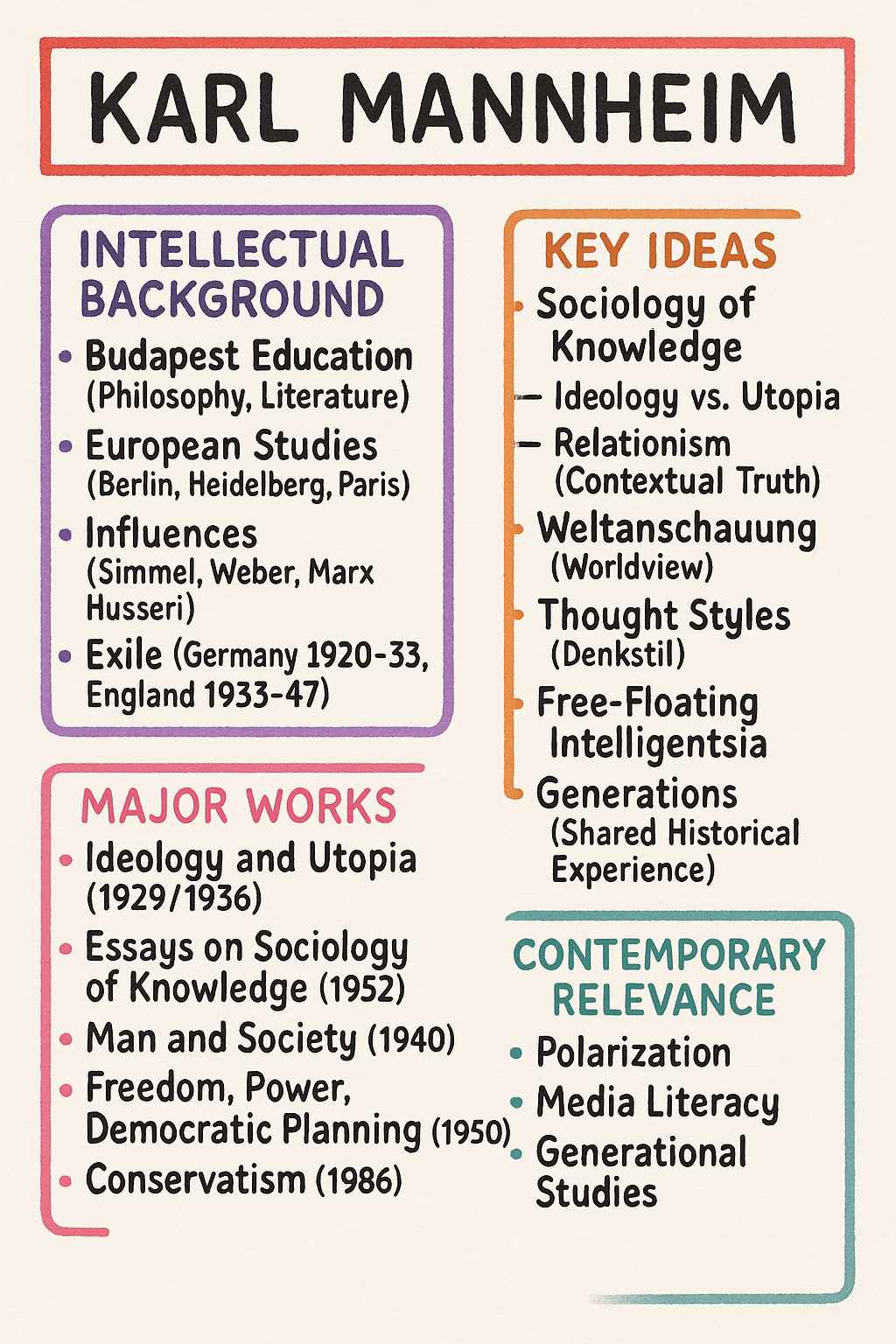

Karl Mannheim (1893–1947), a Hungarian-born sociologist, is widely regarded as a foundational figure in classical sociology and a pioneer of the sociology of knowledge. Born on March 27, 1893, in Budapest to a Hungarian father, a prosperous textile merchant, and a German mother, both of Jewish descent, Mannheim grew up in a secular, culturally rich environment that shaped his intellectual curiosity. His early education at the humanistic gymnasium in Budapest emphasized philosophy and literature, fostering a deep engagement with ideas. Mannheim pursued higher education at the University of Budapest, where he earned his doctorate, and later studied in Berlin, Freiburg, Paris, and Heidelberg, immersing himself in the vibrant intellectual currents of early 20th-century Europe. Influenced by philosophers and sociologists such as Georg Simmel, Max Weber, Alfred Weber, Karl Marx, Edmund Husserl, and Wilhelm Dilthey, Mannheim’s thought was shaped by German historicism, Marxism, phenomenology, and Anglo-American pragmatism. His involvement in Budapest’s intellectual circles, including the Galileo Circle with Karl and Michael Polanyi, the Social Science Association led by Oszkár Jászi, and the Sunday Circle (Sonntagskreis) with György Lukács and Béla Balázs, exposed him to debates on cultural crisis, Marxism, and spiritual renewal. Mannheim’s early work, including his doctoral dissertation Structural Analysis of Epistemology (1922), reflected a philosophical focus, but the political upheavals of the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919 forced him into exile in Germany. There, from 1920 to 1933, he transitioned to sociology, completing his Habilitation thesis on German conservatism at Heidelberg under Alfred Weber and Emil Lederer. The rise of Nazism in 1933 compelled Mannheim to flee to England, where he taught at the London School of Economics (LSE) and later at the University of London’s Institute of Education until his death on January 9, 1947. Mannheim’s intellectual journey, marked by geographical and disciplinary migration, was driven by a quest to understand the relationship between knowledge, society, and politics, culminating in his establishment of the sociology of knowledge as a distinct field. His marriage to psychologist Juliska Károlyné Lang in 1921, who collaborated on many of his works, further enriched his interdisciplinary perspective. Mannheim’s life, shaped by displacement and intellectual synthesis, positioned him to challenge traditional epistemology and advocate for sociology as a tool for democratic education and social reform.

Key Ideas and Concepts

Mannheim’s contributions to sociology are centered on his development of the

sociology of knowledge, a field that examines how social structures and

historical contexts shape human thought. His seminal concept of ideology and

utopia distinguishes between two types of belief systems: ideologies, which

reflect the interests of dominant groups seeking to maintain the status quo,

and utopias, which embody the aspirations of marginalized groups aiming to

transform society. In Ideology and Utopia (1929/1936), Mannheim argued that

all knowledge is “situationally bound” (seinsverbunden), meaning it is rooted

in specific social locations, such as class, status, or generation, and cannot be

fully understood without considering its social origins. This idea, influenced

by Marx’s notion of class-based ideologies, was expanded by Mannheim to

include broader social factors, moving beyond Marxist materialism to

incorporate cultural and historical dimensions. He introduced relationism as

a response to accusations of relativism, proposing that truths are valid within

specific historical and social contexts, not universally absolute, yet still

meaningful. This contrasted with traditional notions of objective truth,

aligning with pragmatist ideas that truth is tied to practical outcomes in

specific situations.

Another key concept is the Weltanschauung (worldview), which Mannheim

defined as the interconnected set of ideas, values, and beliefs that characterize

a historical period or social group. He identified three levels of meaning

within a worldview—objective, expressive, and documentary—allowing for

nuanced analysis of how ideas reflect social realities. Mannheim’s concept of

thought styles (Denkstil) further elaborates this, describing socially

constructed patterns of reasoning tied to specific groups, which explain why

consensus is rare in politically charged debates due to differing premises. His

notion of the free-floating intelligentsia (freischwebender Intelligenz)

posited that intellectuals, loosely anchored to class structures, could

synthesize diverse perspectives into a “dynamic synthesis,” offering a more

comprehensive understanding of social reality. This idea was rooted in his

belief that intellectuals could mediate conflicts by transcending partial

viewpoints, a concept inspired by Alfred Weber and his own experiences as an

exile navigating multiple intellectual traditions.

Mannheim’s focus on generations as a social force, articulated in his 1928

essay “The Problem of Generations,” highlighted how shared historical

experiences shape collective consciousness, influencing cultural and political

outlooks. This concept remains relevant for understanding generational

cohorts like Millennials or Generation Z. He also emphasized political

education and democratic planning, particularly in his British phase,

advocating for sociology to foster “integrative behavior” and “creative

tolerance” in mass societies to counter irrationality and authoritarianism.

Mannheim’s sociology of knowledge sought to rationalize political

decision-making by exposing the social roots of beliefs, promoting dialogue,

and encouraging self-awareness among social groups. His synthesis of

historicism, Marxism, and phenomenology aimed to bridge the gap between

individual agency and social structures, making his work a critical

intervention in understanding the interplay of knowledge, power, and society.

Major Works

Mannheim’s intellectual legacy is encapsulated in several key works that

advanced the sociology of knowledge and its applications. His doctoral

dissertation, Structural Analysis of Epistemology (1922, published 1980), laid the

philosophical groundwork for his later sociological inquiries, exploring how

knowledge is structured and validated. Ideology and Utopia: An Introduction to

the Sociology of Knowledge (1929, English 1936) is his most influential work,

establishing the sociology of knowledge as a distinct field. It introduced the

concepts of ideology, utopia, and relationism, arguing that all thought is

socially conditioned and that intellectuals can synthesize competing

worldviews to approach a more comprehensive truth. The book sparked

significant debate in Germany, with over 30 major responses from intellectuals

like Max Horkheimer and Hannah Arendt, underscoring its impact. Essays on

the Sociology of Knowledge (1952, posthumous) included key articles like “On the

Interpretation of Weltanschauung” (1921–22) and “The Problem of

Generations” (1928), which elaborated his methodological approach to

analyzing worldviews and the role of generational experiences in shaping

thought.

Man and Society in an Age of Reconstruction (1940) addressed the challenges of

mass society, proposing democratic planning to counter authoritarianism and

irrationality. Mannheim argued that sociology could educate citizens for

democratic participation, fostering “integrative behavior” to navigate social

conflicts. Freedom, Power, and Democratic Planning (1950, posthumous) further

developed his ideas on reconciling freedom with social planning, emphasizing

the need for rational, collective decision-making in modern democracies.

Conservatism: A Contribution to the Sociology of Knowledge (1986, posthumous)

analyzed conservative thought as a distinct style shaped by historical and

social conditions, demonstrating Mannheim’s method of tracing thought to its

social roots. Structures of Thinking (1982, posthumous) collected early essays

that showcased his experimental approach to cultural analysis, highlighting

his sensitivity to historical contexts and multiple modes of knowing. These

works collectively illustrate Mannheim’s interdisciplinary approach, blending

sociology, philosophy, and political theory to address the crises of modernity,

from ideological polarization to the rise of totalitarianism.

Critics

Mannheim’s work, while groundbreaking, faced significant criticism,

particularly for its perceived relativism and methodological ambiguities. The

Frankfurt School, including Max Horkheimer, Theodor Adorno, and Herbert

Marcuse, criticized Ideology and Utopia for undermining Marxist principles.

They viewed Mannheim’s sociology of knowledge as neutralizing Marxist

critiques of capitalism by suggesting that all thought, including Marxist

theory, is socially conditioned, thus lacking universal validity. Horkheimer

argued that Mannheim’s approach risked reducing truth to mere social

constructs, threatening the revolutionary potential of Marxism. Similarly,

Hannah Arendt critiqued his relativism for potentially legitimizing competing

ideologies without clear criteria for truth. Mannheim’s concept of relationism,

intended to counter relativism by grounding truth in specific contexts, was

seen by critics like Karl Popper as insufficiently rigorous, accusing him of

undermining reason by tying knowledge too closely to social conditions.

Popper’s critique, articulated in The Open Society and Its Enemies, portrayed

Mannheim’s sociology as dangerously close to justifying irrationalism, though

Mannheim maintained he was reconstructing reason on sociological grounds.

Edward Shils, an American sociologist, criticized Mannheim for

overemphasizing the role of intellectuals, arguing that his notion of the

free-floating intelligentsia exaggerated their ability to transcend social biases.

Shils also questioned the practical feasibility of Mannheim’s proposed

synthesis of worldviews. Marxist critics like György Lukács, Mannheim’s

former friend, accused him of abandoning revolutionary politics for a liberal

reformism that failed to challenge capitalist structures. Mannheim’s focus on

Western intellectual traditions also drew criticism for its Eurocentrism, with

scholars noting its limited applicability to non-Western contexts and its

neglect of intersectional dynamics like race and gender. His later work on

democratic planning was critiqued by conservatives like T.S. Eliot for its

vagueness and by Marxists for its perceived capitulation to liberal capitalism.

At LSE, Mannheim faced institutional challenges, never securing a chair,

partly due to opposition from colleagues like Popper and Friedrich Hayek,

who viewed his ideas as overly idealistic or insufficiently empirical. Despite

these criticisms, defenders like Colin Loader and David Kettler argue that

Mannheim’s focus on the social roots of knowledge was a necessary corrective

to abstract epistemology, and his emphasis on political education remains a

valuable contribution to democratic theory.

Contemporary Relevance

Mannheim’s sociology of knowledge remains profoundly relevant in

addressing contemporary issues of polarization, misinformation, and

democratic crises. His concept of ideology and utopia provides a framework

for understanding the polarized political landscape, where competing

narratives—such as populist movements versus liberal establishments—reflect

distinct social positions. The rise of social media and “fake news” echoes

Mannheim’s concerns about fragmented thought styles, highlighting the need

for critical media literacy to navigate conflicting worldviews. His emphasis on

the social construction of knowledge aligns with contemporary debates in

critical race theory, feminist theory, and postcolonial studies, which explore

how power dynamics shape knowledge production. While critics note

Mannheim’s Eurocentrism, his framework can be adapted to analyze

non-Western contexts by incorporating intersectional perspectives on race,

gender, and colonialism.

Mannheim’s notion of the free-floating intelligentsia resonates with the role

of public intellectuals and academics in mediating political discourse, though

his caution against intellectual elitism underscores the importance of

inclusive, democratic dialogue. His essay “The Problem of Generations” offers

insights into generational divides, such as tensions between Baby Boomers,

Millennials, and Generation Z, informing studies of cultural and political

shis driven by generational experiences. Mannheim’s advocacy for political

education and democratic planning is particularly pertinent in addressing the

rise of illiberal populism and “deformed democracies” in Europe, the United

States, and beyond. His concepts of “integrative behavior” and “creative

tolerance,” echoed in Iris Marion Young’s communicative democracy, provide

strategies for fostering dialogue in diverse, mass societies. For example,

Young’s emphasis on “reasonableness” and inclusion parallels Mannheim’s

call for synthesizing perspectives to counter one-sidedness, offering tools to

address structural injustices in liberal democracies.

Mannheim’s work also informs contemporary sociology’s engagement with

global challenges, such as climate change and migration, where understanding

the social roots of competing narratives is crucial for effective policy-making.

His interdisciplinary approach, integrating sociology, philosophy, and political

theory, inspires scholars to bridge academic and public spheres, using

sociology to promote rational, inclusive decision-making. Despite criticisms of

relativism, Mannheim’s relationism encourages a nuanced understanding of

truth as context-dependent, a perspective valuable in an era of competing

truths and post-truth politics. By highlighting the social foundations of

knowledge, Mannheim’s legacy continues to guide efforts to navigate

ideological conflicts, foster democratic participation, and promote social

cohesion in an increasingly complex world.

References

- The intellectual odyssey of Karl Mannheim: On sociology and political education - akjournals.com

- Karl Mannheim on democratic interaction: Revisiting mass society theory - www.degruyter.com

|

|

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|