Home » Social Thinkers » R.K Merton

R.K Merton

Robert King Merton was a distinguished sociologist perhaps best known for having coined the phrase "self-fulfilling prophecy." He also coined many other phrases that have gone into everyday use, such as "role model" and "unintended consequences". He was heavily influenced by Pitirim Sorokin who tried to balance large-scale theorizing with a strong interest in empirical research and statistical studies. This and Paul Lazarsfeld influenced Merton to occupy himself with middle-range theories.

Robert King Merton was a distinguished sociologist perhaps best known for having coined the phrase "self-fulfilling prophecy." He also coined many other phrases that have gone into everyday use, such as "role model" and "unintended consequences". He was heavily influenced by Pitirim Sorokin who tried to balance large-scale theorizing with a strong interest in empirical research and statistical studies. This and Paul Lazarsfeld influenced Merton to occupy himself with middle-range theories.

Theories of the middle range:

Middle range theories of R.K Merton came as rejection of mega theory of Parsonian sociology. His theory advocates that theory building in sociology should not be governed by intellectual aggression or academic speculation. Sociological theories cannot afford to be rogue, unrealistic, jargon focused and simply logical. Rather theories are developed in sociology to arrange the empirical facts in a consolidated manner. Hence sociological theories should be fact driven. The social theories should be coming out of facts to explain the facts in a systematic manner. Instead of being concerned about mega speculations that there is a social system where there is exchange, negotiation, convergence, consequently control and integration sociology must look into the actual problems and issues related to empirical situations.

During 1960s in America, political corruption, ethnic conflict, deviant behavior was largely manifested and Merton took interest in studying them and explained all the emergent conditions using simply designed theoretical frameworks. Subsequently he identified these theories as middle range theories. As a reaction to mega theories Merton advocates that these theories are highly speculative and do not correspond to the empirical realities. They make an attempt to study every possible dimension of social reality that is not possible in the field of sociology. The degree of abstraction is quite high when concepts are chosen to develop such theories therefore these kind of mega theories do not have much of relevance to understand the essence of social reality. Hence sociology must have to reject mega theoretical constructs replacing them by middle range theories.

Merton is not comfortable with the use of natural science theories in the field of sociology. He advocates that theories in natural science come out of cumulative research made on a given problem by large body of scholars in time and space. It is possible on part of a natural scientist to modify, amend or revise the theories of his predecessors applying such theories to contemporary problems and issues. Natural phenomena being static, cumulative research on them become possible and a broad agreement among the researchers studying the same problem gives rise to the growth of unified theories in the field of natural sciences.

In the field of sociology the form of capitalism, patterns of democracy, role of family as a group keeps changing in time and space. Therefore cumulative research should largely speak about diversity, variabilities present in their structure and functions for which mega theories in sociology may be necessity to natural science but it is absolutely unwanted for sociological research. Sociology must have to go for middle range theories than striving for scientific status extending natural science theories into the field of sociological research. Sociology should not be compared with natural sciences. Merton borrows substantive ideas from sociology of Weber as the basic problem with ideal type construct is that it asserts that totality of reality cannot be studied by sociology therefore sociology must have to study the essence of reality. To Merton sociology is encountering with the problem of identification of the issues for conducting research that needs to be resolved. The weberian sociology is committed to macroscopic issues that are difficult to study in every possible detail. If sociological research considers that it must have to address to microscopic structures then it will not be difficult for sociologists to understand various dimensions to a given social reality therefore Merton takes interest in the study of political corruption, machine politics considering these issues/problems are subjected to complete scientific investigation.

|

|

Middle Range theories in sociology advocate that how to sociological research facts are important than theories. It gives rise to a situation where facts speak for themselves. These theories are small understandable, on controversial universally acceptable conceptual devices coming out of a given empirical situation having capacity to explain same or different types of situations without any possible ambiguities or controversies. For instance reference group theory, concept of in-group or out-group are defined as middle range theories which can provide a guide to sociological research in time and space.

Clarifying functional analysis:

Merton argues that the central orientation of functionalism is in interpreting data by their consequences for larger structures in which they are implicated. Like Durkheim and Parsons he analyzes society with reference to whether cultural and social structures are well or badly integrated, is interested in the persistence of societies and defines functions that make for the adaptation of a given system. Finally, Merton thinks that shared values are central in explaining how societies and institutions work.However he disagrees with Parsons on some issues which will be brought to attention in the following part.

Dysfunctions:

Parsons' work tends to imply that all institutions are inherently good for society. Merton emphasizes the existence of dysfunctions. He thinks that something may have consequences that are generally dysfunctional or which are dysfunctional for some and functional for others. On this point he approaches conflict theory, although he does believe that institutions and values CAN be functional for society as a whole. Merton states that only by recognizing the dysfunctional aspects of institutions, can we explain the development and persistence of alternatives. Merton's concept of dysfunctions is also central to his argument that functionalism is not essentially conservative.

Manifest and latent functions:

Manifest functions are the consequences that people observe or expect, latent functions are those that are neither recognized nor intended. While Parsons tends to emphasize the manifest functions of social behavior, Merton sees attention to latent functions as increasing the understanding of society: the distinction between manifest and latent forces the sociologist to go beyond the reasons individuals give for their actions or for the existence of customs and institutions; it makes them look for other social consequences that allow these practices' survival and illuminate the way society works.Dysfunctions can also be manifest or latent. Manifest dysfunctions include traffic jams, closed streets, piles of garbage, and a shortage of clean public toilets. Latent dysfunctions might include people missing work after the event to recover.

Functional alternatives

Functionalists believe societies must have certain characteristics in order to survive. Merton shares this view but stresses that at the same time particular institutions are not the only ones able to fulfill these functions; a wide range of functional alternatives may be able to perform the same task. This notion of functional alternative is important because it alerts sociologists to the similar functions different institutions may perform and it further reduces the tendency of functionalism to imply approval of the status quo.

Merton's theory of deviance

Merton's structural-functional idea of deviance and anomie.

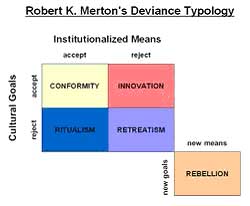

The term anomie, derived from Emile Durkheim, for Merton means: a discontinuity between cultural goals and the legitimate means available for reaching them. Applied to the United States he sees the American dream as an emphasis on the goal of monetary success but without the corresponding emphasis on the legitimate avenues to march toward this goal. This leads to a considerable amount of (the Parsonian term of) deviance. This theory is commonly used in the study of Criminology. (Specifically Strain Theory).| Cultural goals | Institutionalized means | Modes of adaptation |

| + | + | Conformity |

| + | - | Innovation |

| - | + | Ritualism |

| - | - | Retreatism |

| ± | ± | Rebellion |

Conformity is the attaining of societal goals by societal accepted means, while innovation is the attaining of those goals in unaccepted ways. Ritualism is the acceptance of the means but the forfeit of the goals. Retreatism is the rejection of both the means and the goals and rebellion is a combination of rejection of societal goals and means and a substitution of other goals and means. Innovation and ritualism are the pure cases of anomie as Merton defined it because in both cases there is a discontinuity between goals and means.

Sociology of science

Merton carried out extensive research into the sociology of science, developing the Mertonian norms of science. This is a list of ideals that scientists should strive to attain, specifically:R.K. Merton’s Contributions to Sociology

Index

Introduction

Robert K. Merton (1910–2003), born Meyer Robert Schkolnick, was a pioneering American sociologist whose work fundamentally shaped modern sociological theory. His intellectual journey began at Temple University and continued at Harvard University under the mentorship of Talcott Parsons, ultimately leading to a distinguished career at Columbia University. Merton’s contributions are notable for their synthesis of theoretical depth and empirical relevance, making him a central figure in the evolution of sociological thought. His development of middle-range theory, neo-functionalism, and his analyses of manifest and latent functions, reference groups, and conformity and deviance provided durable frameworks for understanding the structures and processes of social life. These ideas continue to influence contemporary research and policy-making, underlining their enduring significance.

Middle-Range Theory and Neo-Functionalism

Merton’s concept of middle-range theory marked a pivotal shift in sociological methodology. In contrast to grand, overarching theories like those of Durkheim or Weber, and narrowly focused empirical studies, middle-range theories aim to explain specific social phenomena that can be empirically tested and modified. This methodological approach bridges the gap between abstract theorizing and real-world data, offering a practical and adaptable framework for theory building.

For instance, Merton used this approach to analyze the functions of social institutions, focusing on observable outcomes rather than attempting to explain all of social life through a single lens. This made his theories more accessible and applicable in diverse contexts than the comprehensive systems theory advanced by Talcott Parsons.

As a neo-functionalist, Merton revised traditional functionalism, which viewed society as a cohesive system of interdependent parts working together for stability. He challenged the assumption that all social practices are inherently beneficial, introducing the concepts of dysfunctions (social practices that disrupt system equilibrium) and non functions (neutral practices). This expanded view allowed him to analyze institutions like education or bureaucracy not only in terms of their intended roles but also in terms of their unintended and even counterproductive consequences. Merton’s insistence on empirical validation reinforced the role of evidence-based inquiry in theory development—an approach that remains central to sociology today.

Manifest and Latent Functions

A cornerstone of Merton’s legacy is his distinction between manifest and latent functions, offering a dual analytical lens for interpreting social behavior.

- Manifest functions are the intended, explicit, and recognized purposes of social practices. For example, the manifest function of education is to transmit knowledge, develop skills, and provide credentials necessary for personal and professional advancement.

- Latent functions, on the other hand, are unintended and often unrecognized outcomes. In schools, these may include peer group formation, reinforcement of obedience to authority, or internalization of social hierarchies—outcomes that significantly influence students’ socialization but are not formally acknowledged in institutional goals.

This framework allows sociologists to uncover the hidden dimensions of institutions. For instance, in the context of competitive examinations, while the manifest function is meritocratic selection, latent functions might include reinforcing class divisions, inducing stress, or favoring the socially privileged who have access to coaching and resources.

A notable example often cited in secondary literature (though not directly by Merton) involves ritual dances: while the manifest belief may center on religious or supernatural purposes, the latent function could be to foster group cohesion and collective identity. This analytical model also helps evaluate policy impacts—for example, the National Food Security Act, which aimed to address hunger but unintentionally influenced rural labor patterns and gender dynamics. Similarly, analyzing latent dysfunctions exposes systemic aws—such as how poor urban infrastructure and inequality in slum areas contribute to deviance and crime.

Reference Groups

Merton’s theory of reference groups brought psychological depth to sociological analysis by explaining how individuals assess their own social position and aspirations in comparison to others. A reference group is a social unit—real or imagined—that an individual uses to evaluate their beliefs, behaviors, roles, and achievements.

These groups are categorized as:

- Membership groups: Those to which an individual currently belongs (e.g., family,workplace).

- Non-membership groups: Those an individual aspires to join or deliberately avoids (e.g., elite professionals, extremist factions).

Reference groups can also be positive (admired and emulated) or negative (rejected and opposed). For example, a young person might view successful civil servants as a positive reference group, guiding their behavior and goals. Conversely, extremist organizations may serve as negative reference groups, prompting individuals to develop alternative norms and moral standards in opposition.

The social implications of reference group behavior are profound. In closed societies, where individuals primarily reference their membership group, social stability and low mobility are common. In contrast, open or dynamic societies promote high mobility, as individuals use non-membership groups as models for aspirational behavior. This can lead to anticipatory socialization, where people adopt the norms of a desired group before gaining membership.

However, this process may result in identity conflict, particularly in contexts with low structural differentiation and blocked opportunities. Merton termed this the “marginal man”—an individual caught between two social worlds, fully belonging to neither. For instance, a working-class youth aspiring to an elite professional career may struggle with self-doubt or societal resistance if systemic inequalities hinder upward mobility

Conformity and Deviance

Merton’s theory of conformity and deviance, rooted in Durkheim’s concept of anomie, marked a major departure from earlier biological or psychological explanations of deviant behavior. Rather than viewing deviance as an individual pathology, Merton located its roots in the structural strain between culturally approved goals (e.g., wealth, success) and the unequal distribution of legitimate means (e.g., education, employment) to achieve them.

He proposed ve modes of individual adaptation to this strain:

1. Conformity: Accepts both cultural goals and legitimate means (e.g., law-abiding

middle class).

2. Innovation: Accepts goals but uses illegitimate means (e.g., criminals who seek

wealth).

3. Ritualism: Abandons goals but strictly follows means (e.g., bureaucrats who lose

sight of purpose).

4. Retreatism: Rejects both goals and means (e.g., addicts or dropouts).

5. Rebellion: Rejects existing goals and means and seeks to replace them with new ones

(e.g., revolutionaries).

Merton’s model explains how structural inequality can lead to different responses to social strain, particularly in societies like the United States, where the “American Dream” promises success to all but delivers it unevenly. For instance, in developing nations, innovation might manifest as corruption or underground economies when legitimate means are inaccessible.

Criticisms of Merton’s Theories

While Merton’s theories are foundational, several critics have highlighted limitations:

- Albert Cohen argued that Merton’s theory is overly focused on financial motives. Delinquent acts like vandalism or violence often stem from status frustration or identity expression, not just blocked opportunity.

- Cloward and Ohlin expanded the theory by incorporating differential access to deviant subcultures, suggesting that not all people with blocked access to legitimate means become deviant—only those with access to illegitimate opportunity structures do.

- Walter Miller emphasized that deviance can arise from subcultural values, such as thrill-seeking or toughness, rather than from goal-mean disparity.

- David Matza, through his theory of “delinquency drift,” highlighted that individuals may temporarily adopt deviant behavior while still holding conventional values, using techniques of neutralization to justify their actions—an area Merton did not address.

- Howard Becker’s labeling theory introduced the idea that being labeled as deviant can lead to further deviance, with primary deviance escalating into secondary deviance due to societal reaction—an insight missing from Merton’s structural approach.

- Finally, the Chicago School focused on social disorganization, arguing that community breakdown, not just anomie, plays a major role in fostering deviance, particularly in urban settings.

Conclusion

R.K. Merton’s contributions—ranging from middle-range theory and functional analysis to reference group theory and anomie-strain theory—have left an indelible mark on sociology. His work refined functionalist thought, grounded sociological theorizing in empirical inquiry, and provided lasting frameworks for understanding both conformity and deviance. While subsequent theorists have exposed the limitations of his models, especially regarding culture, identity, and labeling, these critiques have served to enrich and expand the sociological tradition Merton helped establish. His legacy continues to inform contemporary analyses of institutions, inequality, and social change.

References

- Merton, R. K. (1968). Social Theory and Social Structure (Enlarged ed.). New York: Free Press.

- Merton, R. K. (1957). Continuities in the theory of reference groups and social structure. In Social Theory and Social Structure (pp. 279–334). New York: Free Press.

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|