Sexuality

Index

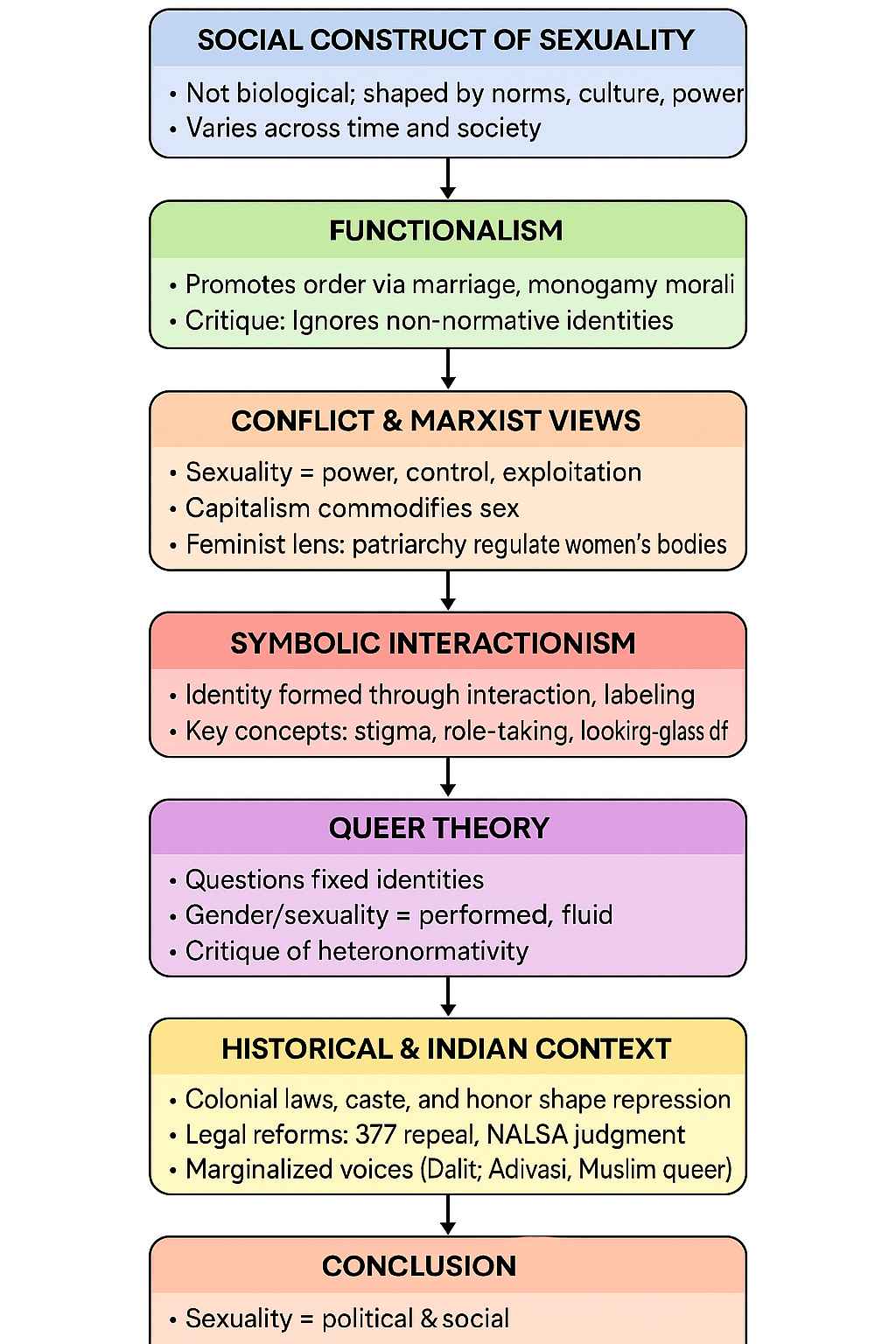

- Introduction to Sexuality as a Social Construct

- Functionalist Perspective on Sexuality

- Critique of Functionalism and Marginalization

- Conflict and Marxist Perspectives on Sexuality

- Feminist Contributions to Sexuality Debates

- Symbolic Interactionism and Sexual Identity

- Queer Theory and the Fluidity of Sexuality

- Institutional Regulation of Sexuality

- Sexual Identities as Historically Shaped

- Sexuality in the Indian Context

- Contemporary Issues in Sexuality (Consent, Technology, Rights)

- Conclusion

Introduction to Sexuality as a Social Construct

Sexuality, though often understood in terms of individual desire and biological instincts, is in fact a deeply social and political construct. In sociology, sexuality is analyzed not simply as a matter of personal choice or natural behavior but as a domain structured by norms, institutions, ideologies, and power relations. It includes a wide spectrum of human experiences: from sexual orientation and identity to practices, desires, taboos, and modes of expression. These are shaped by cultural values, historical processes, religious prescriptions, legal frameworks, and economic arrangements. The very meanings of heterosexuality, homosexuality, virginity, masculinity, and femininity vary across time and space, which indicates their socially constructed nature. Sociologists emphasize that sexuality is not a xed, innate, or universal phenomenon; instead, it is something individuals learn, perform, and negotiate within the social world. The study of sexuality, therefore, provides a powerful lens to understand broader structures of inequality—particularly patriarchy, heteronormativity, casteism, and class power—and the ways they operate through the regulation of bodily autonomy and desire.

Functionalist Perspective on Sexuality

From the perspective of classical sociological theory, functionalists consider sexuality as an institutionally regulated process that serves the needs of social reproduction and stability. Functionalism emphasizes the role of sexuality within the family structure, primarily focusing on its reproductive and moral dimensions. Heterosexuality, monogamy, and marriage are seen as essential for the orderly transmission of values, care for children, and control of population growth. Sexual norms, from this view, maintain moral discipline and prevent social chaos. For instance, traditional societies have often enforced strict codes of sexual conduct through religious morality, kinship systems, and legal sanctions to ensure paternity certainty and inheritance rights. However, this perspective tends to uphold conservative ideals and overlooks the experiences of individuals whose sexual lives deviate from normative scripts. It fails to question who sets the norms and whose interests are served by them. Critics point out that functionalism naturalizes heteronormativity and ignores how sexuality is used to discipline, exclude, or marginalize those who do not conform, including women, LGBTQ+ people, and sex workers.

Critique of Functionalism and Marginalization

Conflict and Marxist Perspectives on Sexuality

In contrast, conflict theorists and Marxist sociologists argue that sexuality is a terrain of struggle, control, and exploitation. According to this view, dominant social groups—whether defined by class, gender, religion, or caste—use institutions to shape sexual norms in ways that reinforce their own interests and power. Karl Marx did not write extensively on sexuality, but his ideas about control of production and ideology laid the foundation for thinkers like Louis Althusser, who argued that education and religion function as ideological state apparatuses that also regulate sexual behavior. Capitalist societies, in particular, commodify sexuality—turning sexual images into products, regulating sexual labor, and criminalizing certain expressions of desire. Feminists further expanded this critique by demonstrating how women’s sexuality is often suppressed, controlled, and objectified within patriarchal frameworks. For instance, women’s chastity is often linked to family honor in traditional settings, leading to coercive practices like virginity testing, honor killings, or connement. Radical feminists like Andrea Dworkin and Catharine MacKinnon have argued that pornography, advertising, and popular culture reduce women to sexual objects and normalize violence against them. Meanwhile, thinkers like Adrienne Rich introduced the concept of “compulsory heterosexuality” to describe how women are pressured into heterosexual relationships by a patriarchal society that erases lesbian identities. Bowles and Gintis, from a Marxist standpoint, argued that schools help reproduce class hierarchies and control labor by regulating students’ behavior—including sexual discipline—through hidden curricula. Pierre Bourdieu contributed significantly with his theory of cultural capital, explaining how children from dominant classes are socialized into “legitimate” expressions of sexuality that are rewarded by institutions, while others face cultural alienation.

Feminist Contributions to Sexuality Debates

Symbolic Interactionism and Sexual Identity

Another important theoretical lens is symbolic interactionism, which focuses on micro-level interactions and the meanings individuals assign to sexual behavior. Unlike macro theories that see sexuality as imposed from above, interactionists explore how people construct their sexual identities and desires through social interaction. George Herbert Mead’s theory of role-taking, Cooley’s “looking-glass self,” and Erving Goman’s concept of stigma help explain how individuals understand themselves as sexual beings based on how others perceive them. For example, when a young person realizes they are attracted to the same gender, they might undergo a complex process of self-definition, shaped by how family, peers, media, and religion interpret such attraction. If labeled as “abnormal” or “deviant,” the individual may internalize shame or resist by creating alternative communities. Howard Becker’s labeling theory is also useful to analyze how people come to see themselves as “gay,” “asexual,” or “trans,” not through biological realization but through interaction and recognition. Interactionists study not just identity formation, but also the negotiation of consent, intimacy, and desire in everyday life. Teachers may treat students differently based on assumptions about their gender or sexuality, reinforcing or challenging norms in subtle ways.

Queer Theory and the Fluidity of Sexuality

Extending the interactionist critique, queer theory emerged in the late 20th century to radically question the stability of identity itself. Queer theorists argue that categories like “gay,” “straight,” “male,” and “female” are not natural but historically contingent and politically constructed. Influenced by poststructuralists like Michel Foucault and Judith Butler, queer theory focuses on the fluidity and performativity of sexuality. Butler’s concept of “gender performativity” asserts that gender and sexuality are not things we are but things we do—through repeated acts, language, dress, and bodily presentation. This challenges both the essentialist idea of biological destiny and the xed identity politics of earlier movements. Queer theory also critiques “heteronormativity,” the institutionalized belief that heterosexuality is the only valid or natural expression of desire. It opens up space for understanding bisexuality, pansexuality, asexuality, non-binary identities, and gender fluidity. Importantly, queer theory calls for the deconstruction of boundaries and the recognition of sexual diversity as not deviant but liberatory

Institutional Regulation of Sexuality

Institutions such as the family, religion, law, education, and media play central roles in the social regulation of sexuality. The family, especially in traditional patriarchal societies, becomes the rst site where norms of sexual behavior are learned and enforced. It often imposes gendered expectations—chastity for women, virility for men—and exercises control over choices in marriage, reproduction, and sexual expression. Religion codifies these norms through sacred texts and moral guidelines, often condemning practices such as premarital sex, masturbation, contraception, or homosexuality. In India, for instance, religious notions of purity and pollution influence ideas of acceptable sexual conduct, especially for women and lower castes. Legal systems reflect the dominant morality of a society. Colonial laws such as Section 377 criminalized same-sex relations for over 150 years in India, even though ancient Indian texts and sculptures openly celebrated sexual diversity. Even after its repeal in 2018, marital rape is still not criminalized, and trans and queer people face systemic discrimination in accessing justice. Schools also enforce sexual norms through the formal and hidden curriculum. Sex education is often absent or moralistic, reinforcing abstinence and ignoring LGBTQ+ realities. The media, meanwhile, plays a dual role: it commodifies sexuality for prot while also policing it through censorship or stereotyping.

Sexual Identities as Historically Shaped

Sexual identities such as heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, or queer are not static biological facts but historically shaped categories. Sociologist Alfred Kinsey, through his studies in the 1940s, demonstrated that sexual orientation exists on a continuum, with most people experiencing a mix of attractions over their lifetime. In many non-Western societies, same-sex intimacy exists without necessarily forming an identity like “gay.” For instance, men who have sex with men in rural India may not identify as homosexual due to lack of vocabulary, fear of stigma, or cultural norms. The process of “coming out” as queer is deeply political—it challenges the invisibility imposed by society and asserts one’s presence in both personal and public life. However, it can also be traumatic and risky, especially in conservative environments. Identities are thus not just discovered but performed, negotiated, resisted, and remade through everyday interactions and collective struggles.

Sexuality in the Indian Context

In the Indian context, sexuality must be examined through the interlocking axes of caste, gender, religion, and colonialism. Ancient Indian texts such as the Kamasutra, temple sculptures at Khajuraho, and the existence of Hijra communities indicate that pre-colonial India had a complex and relatively uid approach to sexuality. However, British colonial rule imposed Victorian morality, criminalized “unnatural acts,” and promoted a rigid gender binary through institutions like the law and education. The caste system has historically controlled sexuality to maintain purity and lineage. Inter-caste love or marriage is still violently opposed in many regions, with honor killings and forced separations being disturbingly common. Post-independence, the Indian state retained many colonial-era laws, and only after decades of activism was homosexuality decriminalized in 2018. The recognition of transgender persons as a third gender in the NALSA judgment (2014) marked a turning point in legal discourse, though implementation remains slow and discriminatory attitudes persist. Queer movements in India—from Pride parades to campus collectives—have pushed for greater inclusion, but queer Dalits, Muslims, and Adivasis often remain at the margins of mainstream queer spaces.

Contemporary Issues in Sexuality (Consent, Technology, Rights)

Contemporary issues in sexuality reflect new challenges and opportunities. The digital era has transformed how people express, explore, and negotiate their sexualities. Dating apps, social media, online communities, and sexting have expanded the realm of intimacy but also brought new risks—cyberstalking, revenge porn, and surveillance. The issue of consent has gained renewed attention, especially with movements like #MeToo. Feminist scholars emphasize the need to move from “no means no” to “yes means yes,” recognizing affirmative and enthusiastic consent as a prerequisite for ethical intimacy. Meanwhile, debates on pornography divide opinion: while some see it as exploitative and reinforcing patriarchy, others argue for feminist pornography that centers female desire and consent. The sexual rights of marginalized groups—like sex workers, disabled individuals, and asexual people—remain under-theorized and under-protected. Intersectional analysis reveals that Dalit queer individuals face multiple layers of violence, both from their own communities and from dominant queer spaces. The struggle for bodily autonomy, pleasure, and self-expression continues to challenge both traditional norms and liberal frameworks.

Conclusion

The sociology of sexuality offers powerful tools to decode how desire, identity, and intimacy are not merely personal matters but deeply shaped by society. It shows how power operates through norms, institutions, and ideologies to regulate sexual behavior, construct categories, and police the body. At the same time, it highlights the ways in which individuals and communities resist, subvert, and reimagine these norms to assert autonomy and dignity. Whether through law reform, queer art, feminist scholarship, or grassroots activism, the discourse on sexuality remains central to the broader pursuit of social justice and human freedom.

References

- Michel Foucault (1976) – The History of Sexuality, Volume I

- Judith Butler (1990) – Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity

- Adrienne Rich (1980) – Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence

- Alfred Kinsey (1948) – Sexual Behavior in the Human Male

Approaches to understanding sexuality are categorized as either essentialist or social constructionist. Essentialism, focusing on the individual expression of human desire and pleasure, favors a biological explanation. Social constructionism, focusing on the relationship between individual and society, explores how sexuality is embedded in historical, political, and social practices.Foucault (1979) traces the history of the heterosexuality/homosexuality dichotomy to processes that began in the nineteenth century and the birth of sexology.

|

|

Challenging essentialist conceptualizations of sex and sexuality as transhistorical and stable categories, Foucault claims that the discursive invention of sexuality as a biological instinct fundamental to understanding an individual's health, pathology and identity lead to biopower.While sex denoted the sexual act, sexuality symbolized the true essence of the individual.Sexual behavior represented the true nature and identity of an individual.While the sexologists favored a biological explanation, Freud's psychoanalytic theory of sexual development led to the psychological construction of different sexual identities. The individual progresses from an initial polymorphous sexuality in early childhood through to the development of a mature stable heterosexual identity in adulthood; homosexuality is a temporary (adolescent) stage of development.To sociologists, sexuality is derived from experiences constructed within social, cultural, and historical contexts. Sexual identities and behaviors develop herein; norms and cultural expectations guide individuals.

Source: The Concise Encyclopedia of Sociology

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|