Home » Social Thinkers » Ralph Dahrendorf

Ralph Dahrendorf

Table of Contents

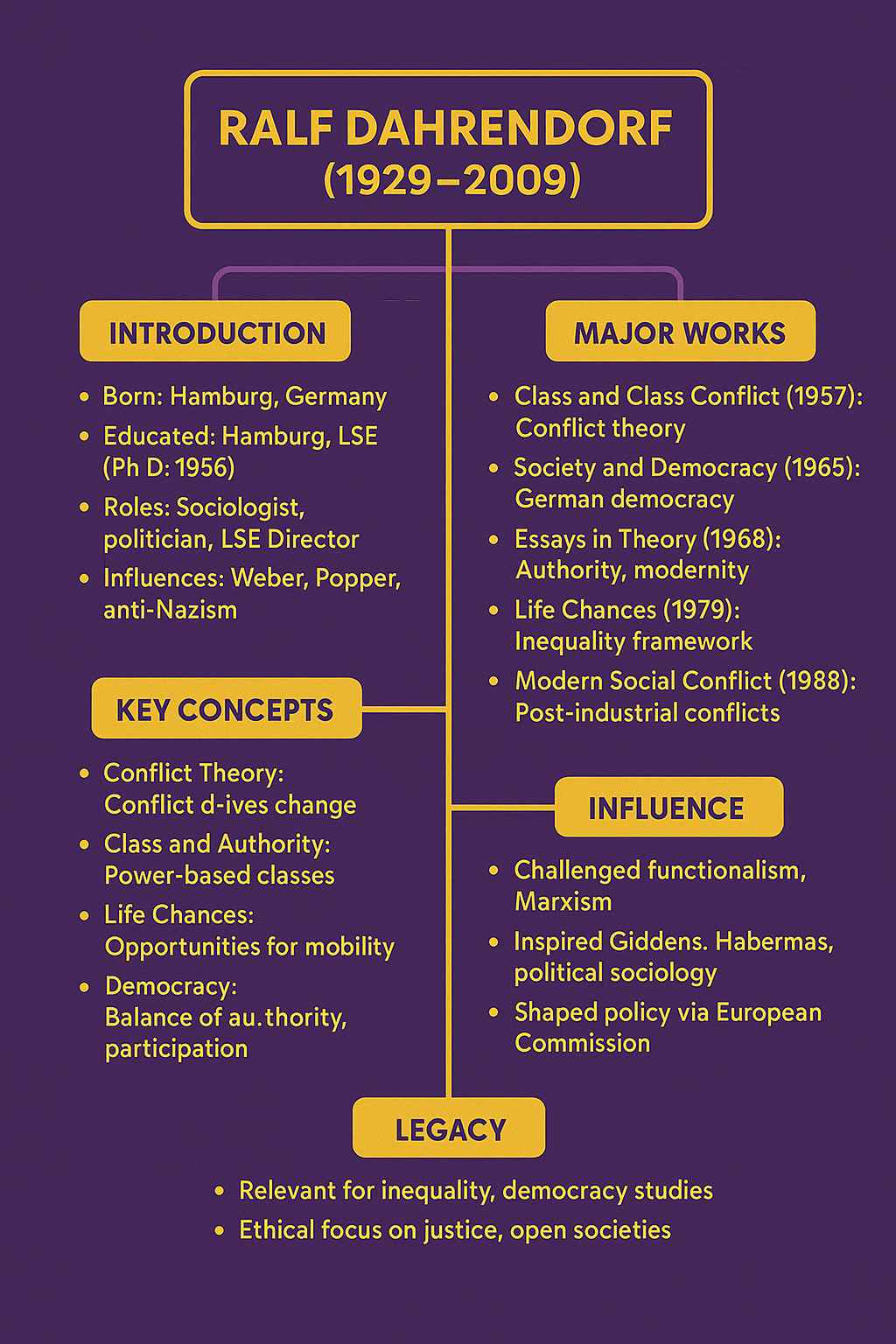

Introduction to Ralf Dahrendorf

Ralf Dahrendorf (1929–2009) was a German-British sociologist, philosopher, and political figure whose work profoundly shaped modern sociology, particularly in the areas of conflict, class, and democracy. Born on May 1, 1929, in Hamburg, Germany, Dahrendorf grew up in a politically engaged family during the rise of Nazism, an experience that deeply influenced his commitment to democratic principles. His father, a Social Democratic politician, was imprisoned by the Nazis, fostering Dahrendorf’s early awareness of power and oppression. He studied philosophy and classics at the University of Hamburg, earning a doctorate in 1952, and later pursued sociology at the London School of Economics (LSE) under Karl Popper, completing a second Ph.D. in 1956. Dahrendorf’s career blended academia and public life, including roles as a German parliamentarian (1969–1970), European Commissioner (1970–1974), and Director of the LSE (1974–1984). Knighted in 1982 and ennobled as Baron Dahrendorf in 1993, he embodied a rare fusion of intellectual rigor and political activism. His work, rooted in Max Weber’s ideas and critical of both Marxism and functionalism, offers sociology students a framework for analyzing power dynamics and social change in modern societies.

Major Works and Contributions

Dahrendorf’s scholarship is characterized by its focus on conflict, authority, and democratic institutions, challenging the consensus-driven paradigms of his time. His seminal work, Class and Class Conflict in Industrial Society (1957), based on his LSE dissertation, critiqued Marxist class theory and Talcott Parsons’ functionalism, proposing a conflict-based model of social change centered on authority relations. This book established him as a leading voice in sociological theory, emphasizing the role of power over economic ownership.

Society and Democracy in Germany (1965) analyzed Germany’s post-war democratic reconstruction, linking social structures to political stability. It explored how historical authoritarianism shaped German society and argued for democratic reforms to foster openness. Essays in the Theory of Society (1968) compiled his theoretical insights on conflict, authority, and modernity, offering a comparative perspective on industrial societies. The New Liberty: Survival and Justice in a Changing World (1975) addressed the tension between liberty and equality, drawing on his political experience to advocate for balanced governance.

Life Chances: Approaches to Social and Political Theory (1979) introduced the concept of “life chances,” a framework for analyzing inequality based on opportunities for social mobility and access to resources. The Modern Social Conflict (1988) synthesized his conflict theory, applying it to post-industrial societies and globalization. Reflections on the Revolution in Europe (1990), written as a letter to a Polish friend, examined the fall of communism and its implications for democratic transitions. These works, grounded in theoretical and empirical analysis, provide sociology students with tools to study power, inequality, and societal transformation.

Key Sociological Concepts

Conflict Theory and Social Change

Dahrendorf’s conflict theory, a cornerstone of his sociology, posits that social change arises from tensions between groups with differing interests, particularly those defined by authority. In Class and Class Conflict in Industrial Society, he rejected Parsons’ functionalist view of society as a harmonious system, arguing instead that conflict is inherent and productive. Unlike Marx, who focused on economic classes, Dahrendorf emphasized conflicts within institutions, such as between managers and workers. He viewed conflict as a driver of progress, fostering reforms and innovation. For sociology students, this theory offers a dynamic lens to analyze social movements, labor disputes, and institutional shis, highlighting conflict’s role in reshaping societal structures.

Class and Authority

Dahrendorf redefined class in terms of authority rather than property ownership, diverging from Marxist orthodoxy. He argued that in industrial societies, power stems from control over decision-making processes within organizations, not just economic resources. In Class and Class Conflict, he distinguished between “ruling” and “subject” groups, with managers, bureaucrats, or elites exercising authority over subordinates. He introduced the concept of “quasi-groups,” latent collectives that could mobilize into organized conflict groups under certain conditions. This perspective is vital for sociology students studying modern organizations, where hierarchical roles shape inequality beyond traditional class lines, such as in corporate or governmental settings.

Life Chances and Social Inequality

In Life Chances, Dahrendorf proposed that inequality should be understood through “life chances,” the opportunities individuals have to achieve well-being, education, and social mobility. Unlike purely economic measures, life chances encompass access to cultural, political, and social resources, influenced by structural factors like class, education, and institutions. This concept integrates Weber’s multidimensional view of stratification with a focus on individual agency. For students, life chances provide a framework to analyze disparities in healthcare, education, or employment, particularly in globalized economies where structural barriers persist.

Democracy and Social Order

Dahrendorf’s work on democracy, notably in Society and Democracy in Germany, emphasized the interplay between social structures and political institutions. He argued that democracy requires a balance between authority and participation to prevent authoritarianism. Drawing on Weber’s concept of legitimate authority, he explored how democratic legitimacy depends on open institutions and citizen engagement. His later works, like The New Liberty, advocated for “open societies” (influenced by Popper) that prioritize individual freedoms and equitable opportunities. This focus equips sociology students to study democratic resilience, especially in contexts of populism or political polarization.

Influence on Sociology and Related Fields

Dahrendorf’s ideas reshaped sociological theory by challenging functionalism and Marxism, offering a conflict-based alternative that resonated with critical theorists like Jürgen Habermas. His collaboration with Karl Popper influenced political philosophy, emphasizing open societies and critical rationalism. Anthony Giddens incorporated Dahrendorf’s authority-based class analysis into structuration theory, enhancing models of agency and power. His comparative studies of German and British societies informed cross-national research, influencing welfare state analyses and political sociology.

In political science, Dahrendorf’s European Commission role and parliamentary experience bridged theory and practice, shaping educational and democratic policies. His critique of Marxism’s economic determinism appealed to post-war intellectuals seeking non-ideological frameworks for social analysis. However, critics like Clifford Geertz noted his reliance on theoretical synthesis over fieldwork, limiting his empirical depth. Despite this, his interdisciplinary approach—spanning sociology, philosophy, and politics—inspired scholars to integrate theory with policy, making his work a cornerstone for applied sociology.

Legacy and Contemporary Relevance

Dahrendorf’s legacy as a public intellectual endures through his theoretical contributions and political engagement. His titles—Sir Ralf in 1982 and Baron Dahrendorf in 1993—reflect his stature, while his leadership of the Liberal Democrats (1988–1990) underscores his commitment to democratic values. The Modern Social Conflict remains a key text for understanding globalization’s impact on class dynamics, relevant to studies of economic inequality and labor markets. His concept of life chances informs contemporary research on social mobility, particularly in addressing systemic barriers like race, gender, or education access.

For sociology students, Dahrendorf’s conflict theory applies to analyzing movements like #MeToo or climate activism, where authority struggles drive change. His democratic theories are pertinent to debates on populism, authoritarianism, and digital governance, offering tools to assess institutional trust. The ethical dimension of his work, rooted in his anti-Nazi background, encourages students to consider sociology’s role in advocating for justice. Critics, however, highlight his Eurocentrism and limited engagement with non-Western societies, a gap addressed by postcolonial scholars. Nonetheless, his ideas remain vital for navigating modern social complexities.

References

- Dahrendorf, R. (1957). Class and Class Conflict in Industrial Society. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Dahrendorf, R. (1965). Society and Democracy in Germany. Weidenfeld & Nicolson

- Dahrendorf, R. (1979). Life Chances: Approaches to Social and Political Theory. University of Chicago Press.

|

|

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|