Home » Social Thinkers » Ralph Linton

Ralph Linton

Index

Introduction

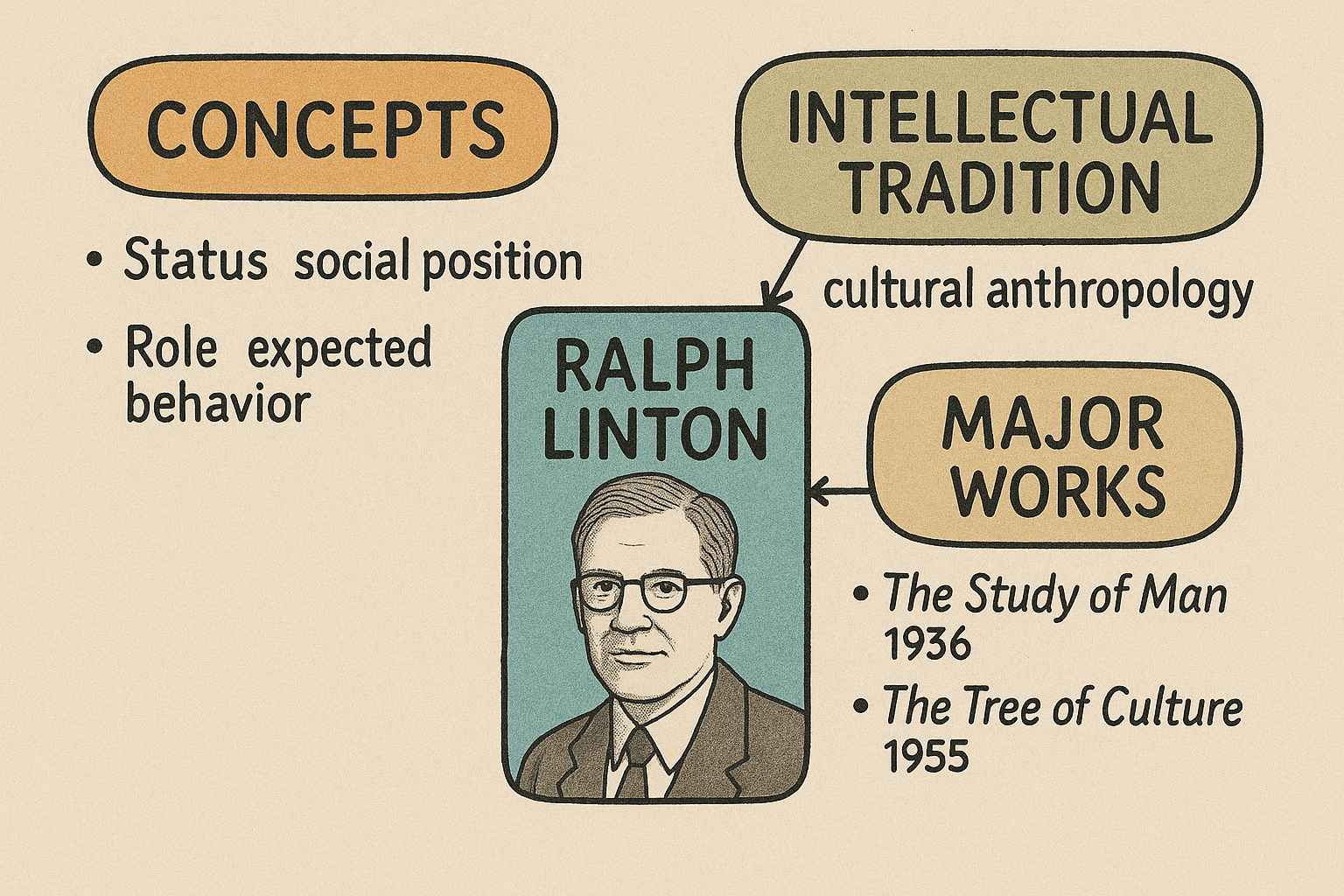

Ralph Linton (1893–1953) was a towering figure in 20th-century American anthropology, renowned for his contributions to cultural anthropology, particularly in the areas of culture, personality, and social roles. Born into a Quaker family in Philadelphia, Linton’s journey from an indifferent student to a leading anthropologist was marked by a deep curiosity about human societies and their cultural underpinnings. His work bridged archaeology, ethnology, and cultural anthropology, offering a holistic approach to understanding human behavior. Linton’s intellectual legacy is encapsulated in his seminal texts, The Study of Man (1936) and The Tree of Culture (1955), as well as his influential concepts of status, role, and acculturation. His career was not without controversy, particularly due to his strained relationships with the Boasian school of anthropology and his actions during the Cold War era. This exploration delves into Linton’s intellectual background, his key ideas, major works, criticisms, and the enduring relevance of his contributions to anthropology and related fields.

Intellectual Background

Ralph Linton was born on February 27, 1893, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to a family of Quaker restaurant entrepreneurs. His early life was shaped by a strict upbringing, which he later described as less than ideal due to his parents’ authoritarian approach. Linton’s academic journey began at Swarthmore College, where he enrolled in 1911. Initially an unenthusiastic student, his interest was sparked by Spencer Trotter, a professor who encouraged him to explore cultures beyond his own. This led Linton to participate in archaeological field schools in New Mexico, Colorado, and Guatemala between 1912 and 1913, igniting a passion for anthropology. After graduating Phi Beta Kappa in 1915, Linton pursued graduate studies at the University of Pennsylvania and later transferred to Harvard University, where he studied under prominent anthropologists like Earnest Hooton, Alfred Tozzer, and Roland Dixon. His graduate education was unconventional, as he never fully aligned with Franz Boas, the dominant figure in American anthropology at the time, partly due to ideological differences and Linton’s military service during World War I, which clashed with Boas’s pacifism.

Linton’s fieldwork experiences were pivotal in shaping his intellectual trajectory. His two-year stay in the Marquesas Islands (1920–1922) shifted his focus from archaeology to ethnology, as he found studying living cultures more rewarding than excavating artifacts. This experience, combined with his later ethnographic expedition to Madagascar (1925–1927), deepened his interest in cultural processes and human behavior. Linton’s time at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago (1922–1928) further honed his skills in material culture and ethnographic research. His appointment at the University of Wisconsin marked a turning point, where he developed as a teacher and theoretician, influenced by interactions with colleagues like Radcliffe-Brown, whose functionalist approach Linton both admired and critiqued. By the time he joined Columbia University in 1937 and later Yale in 1946, Linton had established himself as a leading figure in anthropology, known for his ability to synthesize diverse perspectives and his commitment to empirical fieldwork.

Key Ideas and Concepts

Linton’s contributions to anthropology are distinguished by his development of several key concepts that remain foundational to the discipline. One of his most significant contributions was the distinction between status and role, which he articulated in The Study of Man (1936). Linton defined status as an individual’s social position within a society, while role referred to the behaviors and expectations associated with that position. This framework provided a systematic way to understand the interplay between individuals and social structures, emphasizing how societal norms shape personal behavior. Linton’s concept of status and role became a cornerstone of sociological and anthropological analysis, influencing studies of social organization and individual agency.

Another central idea in Linton’s work was acculturation, which he explored through his fieldwork and later formalized in works like Acculturation in Seven American Indian Tribes (1940). Acculturation described the process by which individuals or groups adopt elements of another culture, often as a result of prolonged contact. Linton’s observations of cultural exchange, particularly during his work with American Indian and Polynesian societies, underscored the dynamic nature of cultural change and the complexities of cultural interaction. His work on acculturation was particularly relevant during his tenure at Columbia’s School of Military Government and Administration, where he trained military personnel to understand foreign cultures, reflecting his practical application of anthropological knowledge.

Linton was also a pioneer in the Culture and Personality school, which examined the interplay between cultural systems and individual psychological development. Collaborating with psychoanalyst Abram Kardiner, Linton developed the basic personality structure theory, which posited that cultural institutions shape a society’s typical personality traits through primary institutions like subsistence patterns and family structures. This theory challenged earlier deterministic views of personality, emphasizing the interaction between environment, culture, and individual psychology. Linton’s work in this area, particularly in The Cultural Background of Personality (1945), highlighted how cultural norms influence personality development, introducing the concept of modal personality structure in collaboration with Cora Du Bois. This concept acknowledged individual variation within cultures while identifying dominant personality traits shaped by cultural practices.

Linton’s approach to culture was notably holistic, blending historical and functionalist perspectives. Unlike Radcliffe-Brown, who dismissed historical analysis in favor of synchronic studies, Linton argued that understanding cultural history was essential to grasping the functions and interdependence of cultural elements. His metaphor of culture as a “banyan tree” in The Tree of Culture (1955) illustrated his view of culture as a complex, interconnected system with roots and branches representing historical and contemporary influences. Linton’s emphasis on enculturation—the process by which individuals internalize their society’s cultural norms—further underscored his belief that culture profoundly shapes personality and social behavior, even among those who deviate from societal norms.

Major Works and Their Explanations

Linton’s scholarly output was prolific, with several works standing out as landmarks in anthropology. His first major publication, The Study of Man (1936), was intended as an introductory textbook for anthropology students but became a defining text in the field. The book synthesized diverse anthropological perspectives, covering human origins, cultural formation, social institutions, and personality development. Linton’s goal was to provide a coherent framework for understanding human societies, integrating insights from archaeology, ethnology, and psychology. While praised for its accessibility and comprehensive scope, the book was criticized for its lack of rigorous documentation, a recurring critique of Linton’s work. Nonetheless, The Study of Man introduced key concepts like status and role and laid the groundwork for Linton’s later theoretical developments.

The Tanala, a Hill Tribe of Madagascar (1933) was a significant ethnographic work based on Linton’s fieldwork in Madagascar. This study detailed the social organization, cultural practices, and historical context of the Tanala people, showcasing Linton’s skill as a fieldworker and his ability to reconstruct cultural histories through ethnographic data. The work reflected his early interest in cultural traits and their distribution, a focus that carried over from his archaeological background. It also highlighted his commitment to empirical research, as he collected a substantial array of artifacts now housed at the Field Museum.

Acculturation in Seven American Indian Tribes (1940) explored the

dynamics of cultural change among Native American groups, drawing on

Linton’s extensive fieldwork. The book examined how contact with

European settlers influenced indigenous cultures, introducing the concept

of acculturation as a framework for understanding cultural adaptation and

resistance. Linton’s analysis was grounded in detailed case studies, making

it a valuable contribution to the study of cultural contact and change.

The Cultural Background of Personality (1945) was a culmination of Linton’s

work in the Culture and Personality school. Based on lectures delivered in

1943, the book explored how cultural systems shape individual

personalities, emphasizing the interplay between culture, society, and

psychology. Linton argued that personality is organized into a central core

(temperament) and a superficial layer (goals and interests shaped by

culture). The book introduced the concept of modal personality structure,

developed in collaboration with Cora Du Bois, which posited that cultures

foster specific personality types while allowing for individual variation.

This work was influential in bridging anthropology and psychology,

though it faced criticism for its speculative assertions.

Linton’s final major work, The Tree of Culture (1955), was published posthumously and completed by his wife, Adelin Hohlfeld, based on his notes. This ambitious book attempted a global synthesis of cultural history, tracing the development of human societies from prehistory to the present. Linton’s metaphor of culture as a banyan tree emphasized the interconnectedness of cultural elements across time and space. While praised for its bold scope and engaging style, the book was criticized for its lack of empirical rigor and for overlapping significantly with The Study of Man. Despite these critiques, The Tree of Culture remains a testament to Linton’s synthetic approach to anthropology.

Critics

Linton’s career was not without controversy, particularly regarding his professional relationships and political actions. His strained relationship with the Boasian school, led by Franz Boas, was a significant source of criticism. Linton’s appointment as head of Columbia University’s anthropology department in 1937, following Boas’s retirement, was met with resistance from Boas’s students, who favored Ruth Benedict for the role. Linton’s personal animosity toward the Boasians, particularly Benedict, was well-documented, with some accounts suggesting he harbored intense dislike, even jokingly claiming to have used a Tanala magic charm against her. His intellectual critiques of the Boasian Culture and Personality approach, which he viewed as overly focused on psychological determinism, further fueled this rift.

More controversially, Linton’s actions during the Cold War era drew

significant criticism. He informed the FBI about colleagues he suspected of

communist sympathies, including Boas and his students like Gene

Weltfish, leading to some being fired or blacklisted. This McCarthy-era

involvement tarnished Linton’s reputation among peers, who viewed his

actions as a betrayal of academic integrity. Critics also pointed to Linton’s

tendency to make broad theoretical claims without sufficient empirical

evidence, a critique leveled at both The Study of Man and The Tree of

Culture. Some argued that his synthetic approach sacrificed depth for

breadth, resulting in generalizations that lacked rigorous documentation.

Linton’s collaboration with Radcliffe-Brown also sparked intellectual

debates. While Linton admired Radcliffe-Brown’s functionalist approach,

he rejected the dismissal of historical analysis, arguing that understanding

cultural history was essential to anthropological inquiry. This tension

highlighted Linton’s unique position between functionalism and historical

particularism, but it also drew criticism from those who felt he failed to

fully reconcile these approaches. Despite these critiques, Linton’s ability

to engage broad audiences and his role in popularizing anthropology

through works like “One Hundred Percent American” (1937) were widely

acknowledged, even by his detractors.

Contemporary Relevance

Linton’s work remains highly relevant in contemporary anthropology and

related fields, particularly in the study of culture, identity, and social roles.

His concepts of status and role continue to inform sociological and

anthropological analyses of social structures, influencing fields like

organizational sociology and social psychology. These concepts are

especially pertinent in studies of workplace dynamics, gender roles, and

social stratification, where the interplay between individual behavior and

societal expectations is a central concern.

The concept of acculturation is increasingly relevant in today’s globalized

world, where cultural contact and migration are commonplace. Linton’s

framework for understanding cultural change provides a foundation for

studying phenomena like diaspora communities, cultural hybridity, and

globalization’s impact on indigenous cultures. His work on acculturation is

cited in contemporary research on multiculturalism and intercultural

communication, offering insights into how individuals and groups navigate

cultural transitions.

Linton’s contributions to the Culture and Personality school continue to

resonate in psychological anthropology and cross-cultural psychology.

The basic and modal personality structure theories inform research on

how cultural contexts shape mental health, identity formation, and social

behavior. For example, studies of collectivist versus individualist societies

often draw on Linton’s ideas about how cultural norms influence

personality traits. His emphasis on enculturation is also relevant in

educational anthropology, where researchers examine how cultural values

are transmitted through socialization processes.

However, Linton’s legacy is tempered by his controversial actions during

the Cold War. His involvement in McCarthy-era politics serves as a

cautionary tale about the ethical responsibilities of academics, particularly

in politically charged climates. Contemporary scholars reflect on Linton’s

actions as a reminder of the need to balance academic freedom with

ethical integrity. Despite these controversies, Linton’s holistic approach to

anthropology—integrating history, culture, and psychology—continues to

inspire interdisciplinary research, making his work a vital part of the

anthropological canon.

References

- Bohannon, P., & Glazer, M. (1988). High points in anthropology. New York, NY: Knopf.

- Kardiner, A., & Linton, R. (1939). The individual and his society: The psychodynamics of primitive social organization. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Kardiner, A., Linton, R., Du Bois, C., & West, J. (1945). The psychological frontiers of society. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Linton, R. (1933). The Tanala, a Hill Tribe of Madagascar. Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History.

- Linton, R. (1936). The study of man: An introduction. New York, NY: D. Appleton-Century.

- Linton, R. (1940). Acculturation in seven American Indian tribes. New York, NY: D. Appleton-Century.

- Linton, R. (1945). The cultural background of personality. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Linton, R. (1955). The tree of culture. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

|

|

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|