Home » Social Thinkers » Herbert Marcuse

Herbert Marcuse

Index

Introduction

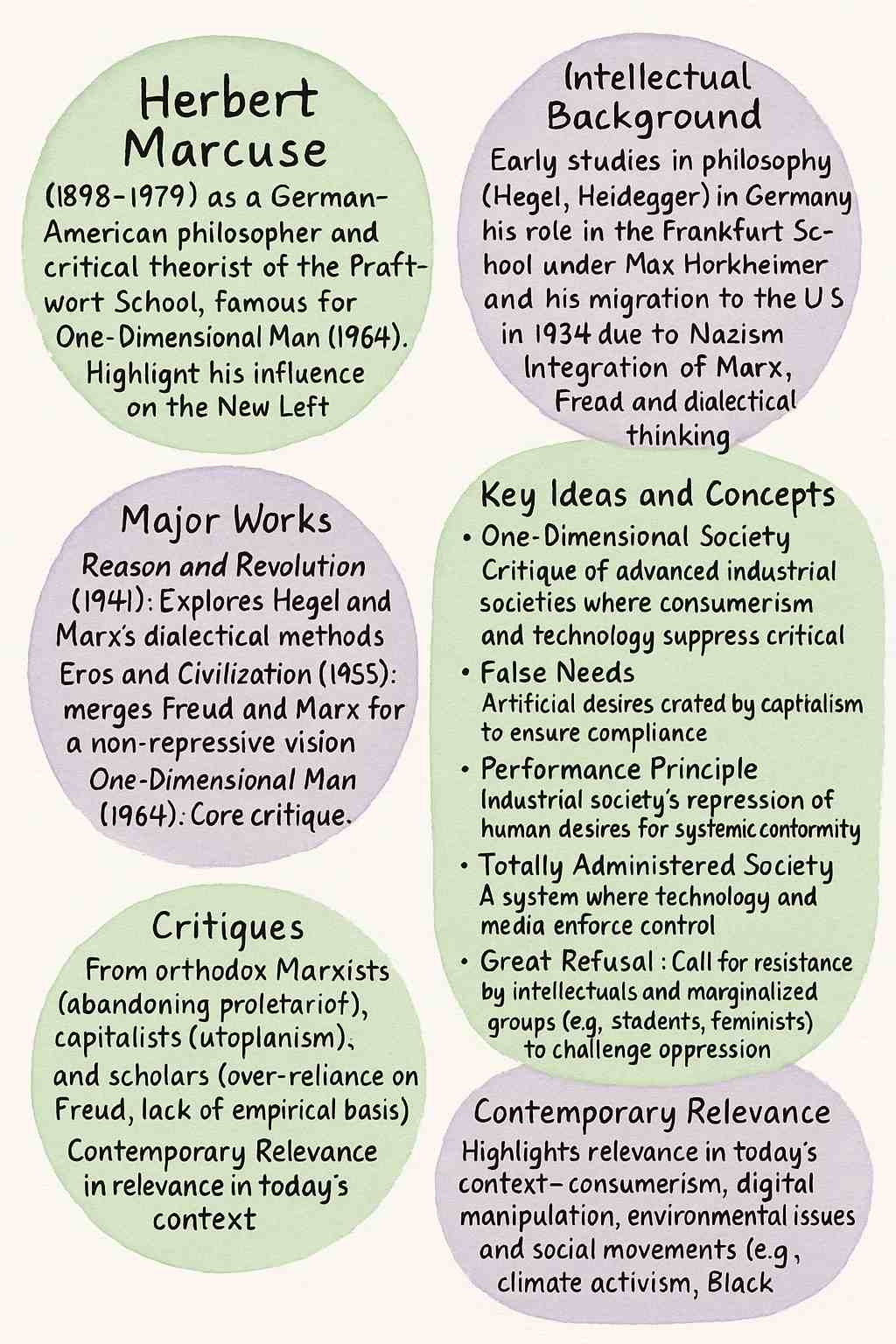

Herbert Marcuse (1898–1979) was a German-American philosopher, sociologist, and political theorist whose work profoundly shaped the intellectual landscape of the 20th century, particularly within the framework of critical theory and the New Le movements. Oen regarded as one of the most influential figures of the Frankfurt School, Marcuse gained widespread recognition with his seminal book One-Dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society (1964), which critiqued the pervasive conformity and repression in both capitalist and communist societies. His ideas resonated with the radical youth of the 1960s, inspiring student protests against militarism, consumerism, and conservative values, particularly during the Vietnam War era. Marcuse’s blend of Marxist thought, Freudian psychoanalysis, and Hegelian philosophy offered a radical critique of modern industrial society, advocating for a non-repressive civilization that prioritizes human freedom and creativity over materialistic domination. His legacy continues to influence social movements and academic discourse on liberation and resistance.

Intellectual Background

Marcuse’s intellectual development was deeply rooted in the rich philosophical and political traditions of early 20th-century Germany. Born in Berlin to a Jewish family, he served in the German Army during World War I before pursuing studies in philosophy, economics, and literature at the universities of Berlin and Freiburg. His early engagement with the works of Immanuel Kant, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, and Martin Heidegger laid a strong philosophical foundation, with Heidegger’s existentialism initially influencing his thought. However, Marcuse’s intellectual trajectory shied significantly when he joined the Institute for Social Research in Frankfurt in 1933, becoming a key member of the Frankfurt School under the leadership of Max Horkheimer. This interdisciplinary group sought to update Marxist theory to address the complexities of modern capitalism, fascism, and mass culture, integrating Freudian psychoanalysis with Marxian materialism. The rise of Nazism forced Marcuse to flee Germany in 1934, and aer a brief period in Switzerland and France, he settled in the United States in 1934, where he worked for the Office of Strategic Services during World War II. Later, he held academic positions at Brandeis University and the University of California, San Diego, continuing to refine his critical theory in dialogue with scholars like Theodor Adorno and Jürgen Habermas. This fusion of European philosophical traditions with American social realities shaped Marcuse’s unique perspective on oppression and liberation.

Key Ideas and Concepts

At the core of Marcuse’s thought is the critique of advanced industrial society as a “one-dimensional” system that suppresses critical thinking and human potential. He argued that modern capitalism, through new forms of social control, creates “false needs”—artificial desires for consumer goods that bind individuals to the system rather than fulfilling genuine human aspirations. This concept builds on Karl Marx’s idea of alienation, extending it to suggest that individuals identify their identities with commodities, such as cars or gadgets, rather than their own creative capacities. Marcuse introduced the “performance principle,” a modification of Freud’s reality principle, to describe how industrial society channels human drives into conformity with systemic demands, stifling Eros (desire) in favor of Logos (reason) dominated by technological rationality. He also developed the notion of a “totally administered society,” where technology and mass media enforce a seamless integration of individuals into a repressive structure, undermining revolutionary potential. In response, Marcuse proposed the “Great Refusal,” a call for radical opposition by marginalized groups—such as students, feminists, and racial minorities—alongside intellectuals, to challenge the dominant ideology and envision a liberated society. His emphasis on dialectical thinking, rooted in Hegel and Marx, underscored the need to recognize and overcome societal contradictions to achieve true freedom.

Major Works and Their Explanations

Marcuse’s intellectual contributions are best captured in several landmark works that reflect his evolving critique of society. His first major English-language book, Reason and Revolution: Hegel and the Rise of Social Theory (1941), explores the philosophical underpinnings of Hegel and Marx, offering a dialectical approach to understanding the contradictions within industrial societies. This work is celebrated as an accessible introduction to dialectical thinking and its relevance to social change. In Eros and Civilization: A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud (1955), Marcuse synthesizes Freudian psychoanalysis with Marxist theory, critiquing the repressive nature of the performance principle in industrial society. He advocates for a non-repressive civilization where human desires and creativity are liberated, a vision that inspired the counter cultural movements of the 1960s. His most famous work, One-Dimensional Man (1964), provides a comprehensive analysis of advanced industrial societies, arguing that consumerism, mass media, and technology create a one-dimensional universe that eliminates dissent and critical thought. Marcuse examines how these mechanisms integrate the working class into capitalism, rendering them incapable of revolution, and suggests that liberation lies with new social actors. Additionally, An Essay on Liberation (1969) expands on the Great Refusal, celebrating the potential of student and anti-war movements to overthrow oppressive structures. These works collectively articulate Marcuse’s vision of a society free from domination, blending theoretical depth with practical political implications.

Critiques

Marcuse’s ideas have faced significant criticism from various quarters. Orthodox Marxists accused him of deviating from classical Marxism by abandoning the proletariat as the revolutionary class, instead placing hope in marginalized groups, which they viewed as an anarchic dilution of Marxist principles. Capitalist defenders, on the other hand, criticized his rejection of consumerism and technological progress as a threat to economic stability and social order, labeling his ideas as utopian or impractical. Some scholars argue that his reliance on Freudian concepts, such as the performance principle, lacks empirical grounding and overemphasizes psychological repression over material conditions. Additionally, his optimistic portrayal of the Great Refusal has been questioned for underestimating the resilience of capitalist structures and the challenges of sustaining radical movements. Critics also note that One-Dimensional Man offers a pessimistic view of human agency, suggesting that individuals are too deeply integrated into the system to resist effectively. Despite these critiques, supporters contend that Marcuse’s work provides a vital critique of modern society’s repressive tendencies, complementing rather than contradicting Marxist analysis.

Contemporary Relevance

Marcuse’s ideas remain strikingly relevant in today’s globalized world, where the themes he explored—consumerism, technological control, and the erosion of critical thinking—have intensified. The proliferation of digital technology, social media, and fake news aligns with his warnings about mass media shaping one-dimensional thought, as individuals are increasingly manipulated by algorithms and advertising that create false needs. The environmental crisis, driven by over consumption and resource exploitation, echoes his critique of industrial society’s irrational destruction under the guise of progress. His analysis of a totally administered society finds resonance in surveillance capitalism, where data collection and behavioral manipulation mirror the social control he described. The Great Refusal finds echoes in contemporary movements like climate activism, Black Lives Matter, and feminist struggles, which challenge systemic oppression and align with his call for radical intellectuals and marginalized groups to lead change. Scholars like Douglas Kellner highlight how Marcuse’s focus on liberation from false needs offers a framework for resisting the commodification of life in the digital age. As societies grapple with inequality, ecological threats, and the impact of globalization, Marcuse’s vision of a non-repressive civilization provides a compelling lens for rethinking freedom and resistance.

References

- Kellner, Douglas. (2002). Introduction (Marcuse, H. One-Dimensional Man, 2nd Edition). New York and London: Routledge.

- Marcuse, Herbert. (1941). Reason and Revolution: Hegel and the Rise of Social Theory. Oxford University Press.

|

|

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|