Home » Social Thinkers » Franz Boas

Franz Boas

Index

Introduction and Intellectual Background

Franz Uri Boas (1858–1942), oen hailed as the “Father of American

Anthropology,” was a transformative figure whose work reshaped the study of

human societies, challenging prevailing notions of race, culture, and human

development. Born on July 9, 1858, in Minden, Westphalia, Germany, Boas

grew up in a liberal, intellectually vibrant Jewish household that valued the

ideals of the 1848 revolutions. His parents, Meier Boas and Sophie Meyer,

fostered an environment of free thought, encouraging intellectual curiosity

and skepticism toward dogma. From an early age, Boas displayed a keen

interest in the natural sciences, including botany, zoology, and geography,

which he pursued at the Gymnasium in Minden and later at the universities of

Heidelberg, Bonn, and Kiel. In 1881, he earned a Ph.D. in physics with a minor

in geography from the University of Kiel, a testament to his rigorous scientific

training. However, his intellectual trajectory shied dramatically during a

year-long expedition to Baffin Island in 1883–84, where he studied the Inuit.

This experience ignited a fascination with human cultures, steering him

toward anthropology.

Boas’s early intellectual influences were rooted in the German academic

tradition, particularly the Enlightenment ideas of Immanuel Kant and the

counter-Enlightenment emphasis on human creativity by Johann Gottfried

Herder. At the Royal Ethnological Museum in Berlin, he worked under Adolf

Bastian, whose concept of the “psychic unity of mankind” posited that all

humans share the same intellectual capacity, with cultural differences arising

from historical and environmental factors rather than biological determinism.

This perspective resonated with Boas, who rejected the environmental

determinism and racial hierarchies that dominated 19th-century thought.

Alienated by rising antisemitism and limited academic opportunities in

Germany, Boas emigrated to the United States in 1887, initially working as an

assistant editor for Science magazine and later as a curator at the Smithsonian

Institution. In 1899, he became a professor of anthropology at Columbia

University, where he established the first anthropology department in the

United States, training a generation of scholars who would carry his ideas

forward. His interdisciplinary background in physics, geography, and

ethnology, combined with his commitment to empirical research, positioned

him to challenge the pseudoscientific racism and evolutionary models of his

time, laying the foundation for modern anthropology.

Key Ideas and Concepts

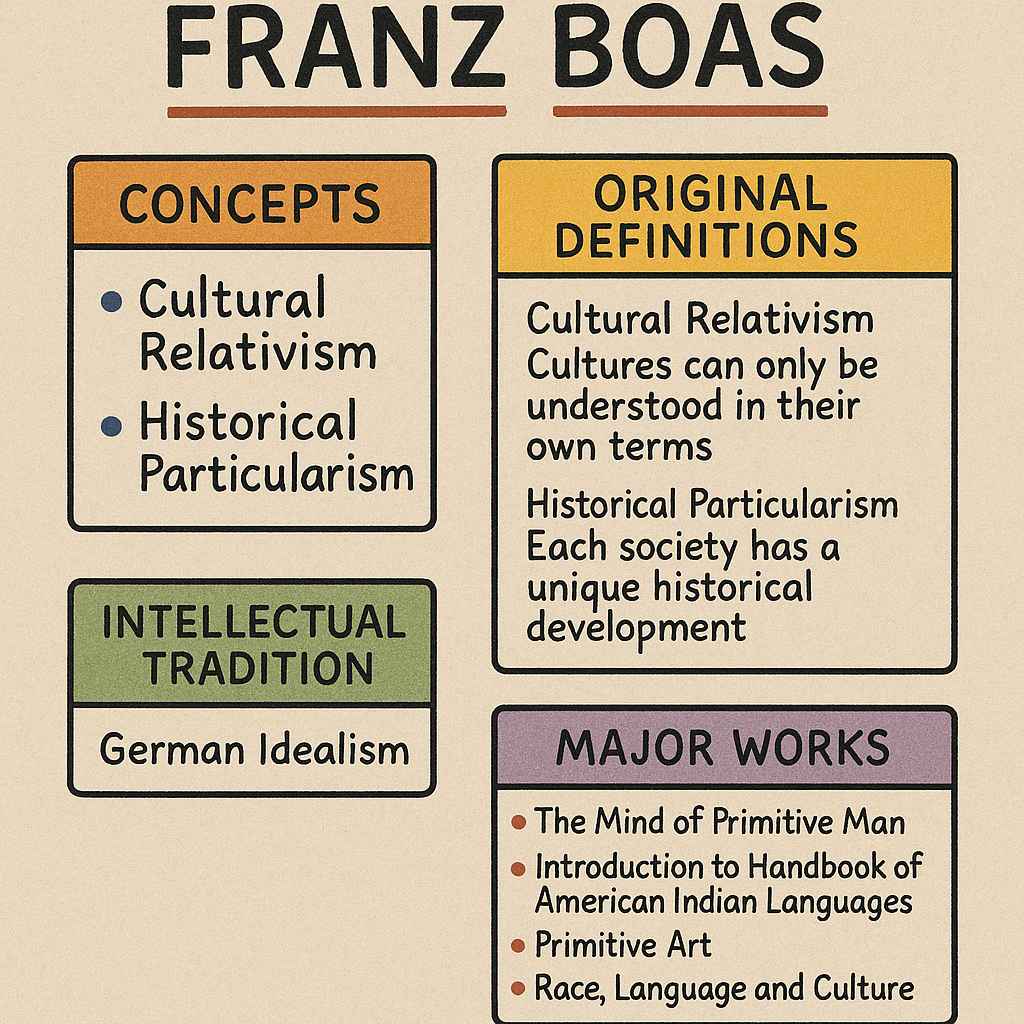

Boas’s contributions to anthropology are encapsulated in his development of

cultural relativism, historical particularism, and the four-field approach,

which fundamentally altered how scholars understood human diversity.

Cultural relativism, one of his most enduring legacies, posits that cultures

must be understood on their own terms, without judgment based on Western

or ethnocentric standards. Boas argued that no culture is inherently superior

or inferior, challenging the evolutionary theories of the 19th century, such as

those of Edward B. Tylor and Lewis Henry Morgan, which ranked societies on

a linear scale from “savagery” to “civilization.” He emphasized that cultural

practices and beliefs are shaped by specific historical and social contexts, not

by universal stages of progress. This idea was revolutionary in an era when

Social Darwinism and scientific racism justified colonialism and racial

hierarchies. Boas’s 1911 study of immigrant head shapes for the U.S. Census

Commission demonstrated the plasticity of physical traits, showing that

environmental factors like nutrition and living conditions, rather than fixed

racial characteristics, influenced cranial measurements. This work debunked

claims of racial determinism, asserting that human behavior and capabilities

are primarily products of cultural learning, not biology.

Historical particularism, another cornerstone of Boas’s thought, rejected the

notion that all societies follow a universal developmental path. Instead, he

argued that each culture is the product of its unique historical circumstances,

shaped by interactions, migrations, and diffusion of ideas. This approach

contrasted with the unilineal evolutionism of his contemporaries, who

assumed Western European culture represented the pinnacle of human

progress. Boas advocated for meticulous, empirical fieldwork to document the

specific histories and practices of individual societies, emphasizing the

importance of understanding cultures from the perspective of their members.

His rejection of grand, universal theories in favor of detailed, context-specific

studies shied anthropology toward a more scientific and less speculative

discipline.

Boas’s four-field approach integrated physical anthropology, cultural

anthropology, archaeology, and linguistics into a holistic framework for

studying humanity. He believed that understanding human societies required

examining biological, historical, cultural, and linguistic dimensions together.

For example, his linguistic work with Indigenous languages, particularly those

of the Pacific Northwest, underscored the role of language in shaping cultural

identity and worldview. By establishing the International Journal of American

Linguistics, Boas advanced the study of Native American languages, preserving

endangered languages and demonstrating their complexity. His holistic

approach emphasized interdisciplinary methods, drawing from biology,

history, and psychology to provide a comprehensive understanding of human

diversity.

Boas also championed the concept of culture as dynamic, arguing that

cultures are not static or monolithic but constantly evolving through

individual agency and historical processes. In his 1920 essay, “The Methods of

Ethnology,” he stressed that anthropology should focus on how individuals

interact with their social environments and how their actions drive cultural

change. This view challenged the idea of cultures as fixed or uniform,

highlighting their fluidity and adaptability. Boas’s emphasis on empirical

fieldwork, cultural context, and the rejection of racial and evolutionary

hierarchies laid the groundwork for modern anthropological theory and

practice.

Major Works and Their Explanations

Boas’s prolific output includes several seminal works that remain foundational

in anthropology. His first major publication, The Central Eskimo (1888), based

on his Baffin Island fieldwork, provided a detailed ethnographic account of

Inuit life, emphasizing their cultural practices and environmental adaptations.

This work marked the beginning of his commitment to firsthand observation

and documentation, setting a standard for ethnographic research. The Mind of

Primitive Man (1911) is perhaps his most influential book, synthesizing his

arguments against racial determinism and evolutionary hierarchies. Boas

asserted that human mental capacities are universal, with differences in

behavior and thought arising from cultural, not biological, factors. The book

laid the conceptual foundation for cultural relativism, challenging the notion

that so-called “primitive” societies were inherently inferior.

Handbook of American Indian Languages (1911) was a groundbreaking

contribution to linguistic anthropology, compiling detailed analyses of Native

American languages and demonstrating their structural complexity. Boas

argued that language shapes cultural perception, a concept later expanded by

his student Edward Sapir. Anthropology and Modern Life (1928) addressed

contemporary social issues, such as racism, nationalism, and education,

advocating for anthropology as a tool for social reform. Boas urged readers to

embrace critical thinking and reject stereotypes, emphasizing the discipline’s

relevance to modern challenges. Race, Language, and Culture (1940), a collection

of essays, encapsulated his lifelong work on the interplay of biology, language,

and culture, reinforcing his argument that human differences are primarily

cultural, not racial. Primitive Art (1927) explored the aesthetic and symbolic

dimensions of non-Western art, challenging Eurocentric notions of artistic

value and highlighting the creativity of Indigenous cultures.

Boas’s work extended beyond academic publications. His curatorial efforts at

the Smithsonian and the American Museum of Natural History revolutionized

museum displays by presenting cultural artifacts in their historical and social

contexts, rather than as evolutionary curiosities. His role in the 1893 Chicago

World’s Fair, where he showcased Native American cultures, brought

anthropological insights to a broader public. Through these works, Boas not

only advanced anthropological theory but also made it accessible and relevant

to societal debates on race, culture, and equality.

Critics

Despite his towering influence, Boas faced significant criticism and

controversies during and aer his lifetime. His outspoken opposition to

scientific racism and nationalism made him a target for conservative

anthropologists and political figures. In 1919, Boas published a letter in The

Nation criticizing anthropologists who spied for the U.S. government during

World War I, arguing that such actions undermined the integrity of the

discipline. This led to his censure by the American Anthropological

Association (AAA) in 1919, with a vote of 20 to 10, forcing his resignation as

the AAA’s representative to the National Research Council. The censure,

driven by figures like Samuel Lothrop and Roland Dixon, was not rescinded

until 2005, reflecting the contentious nature of Boas’s activism. Critics

accused him of endangering anthropologists abroad by questioning their

neutrality, though Boas maintained that ethical scholarship required

transparency and independence.

Boas’s rejection of evolutionary theories and his emphasis on historical

particularism drew criticism from anthropologists who favored universal

models of cultural development. Leslie White, a prominent critic, argued that

Boas’s focus on descriptive ethnography lacked theoretical rigor, accusing him

of reducing anthropology to mere data collection. White and others in the

mid-20th century, influenced by cultural evolutionism, viewed Boas’s

particularism as overly relativistic, potentially undermining efforts to identify

universal cultural patterns. Postmodern and postcolonial scholars in the 1960s

and beyond criticized Boas for not fully addressing power dynamics in

colonial contexts, arguing that his cultural relativism could inadvertently

downplay the impact of imperialism on Indigenous peoples. Herbert S. Lewis,

however, defended Boas, noting that his anti-racist activism and support for

Indigenous communities aligned with the values of his later critics.

Boas’s mentorship style also sparked debate. While he trained a remarkable

cohort of students, including Margaret Mead, Ruth Benedict, Zora Neale

Hurston, and Alfred Kroeber, some described him as overbearing or

insufficiently supportive in preparing students for fieldwork. His rigorous

standards and directive approach occasionally strained relationships, though

his students’ success attests to the effectiveness of his mentorship.

Additionally, his 1910–12 study on immigrant head shapes, while

groundbreaking, was later criticized for overstating environmental influences

on physical traits, with modern reassessments suggesting methodological

flaws. Despite these critiques, Boas’s commitment to empirical rigor and

social justice remains widely respected, with many of his ideas vindicated by

later scholarship.

Contemporary Relevance

Boas’s ideas continue to resonate in contemporary anthropology and beyond,

particularly in discussions of race, cultural diversity, and social justice. His

concept of cultural relativism remains a cornerstone of anthropological ethics,

guiding researchers to approach cultures without ethnocentric bias. In an era

of globalization and cultural exchange, Boas’s emphasis on understanding

societies in their historical and social contexts informs cross-cultural studies

and efforts to preserve endangered languages and traditions. His rejection of

scientific racism is especially relevant in addressing persistent issues of racial

inequality and discrimination. Boas’s work influenced landmark decisions,

such as the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court ruling against “separate but equal”

policies, by providing scientific evidence that race is a social, not biological,

construct. His collaboration with figures like W.E.B. Du Bois and his

mentorship of Zora Neale Hurston contributed to the Harlem Renaissance,

highlighting the cultural richness of African and African-American traditions.

Boas’s four-field approach continues to shape anthropology as a holistic

discipline, encouraging interdisciplinary methods that integrate biology,

linguistics, archaeology, and cultural studies. His advocacy for rigorous

fieldwork and empirical data collection remains a methodological standard,

ensuring that anthropological research is grounded in firsthand observation.

His activism against fascism, racism, and censorship—particularly his efforts

to aid refugee scholars fleeing Nazi Germany—offers a model for public

intellectuals today. In an age of rising nationalism and xenophobia, Boas’s

insistence on the equality of all cultures and his critique of ethnocentrism

provide a framework for combating prejudice and fostering mutual

understanding.

Moreover, Boas’s legacy extends to contemporary debates on decolonizing

anthropology. While some critics argue that his work did not fully address

colonial power dynamics, his emphasis on Indigenous agency and cultural

complexity laid the groundwork for later decolonial approaches. His

documentation of Native American languages and cultures, such as the

Kwakiutl, has supported Indigenous communities in reclaiming their heritage

and asserting legal rights. Boas’s call for anthropology to engage with social

issues, as articulated in Anthropology and Modern Life, resonates with modern

scholars who use anthropology to address climate change, migration, and

human rights. His vision of anthropology as a tool for social change continues

to inspire researchers to challenge stereotypes and advocate for marginalized

groups, ensuring his enduring relevance in a rapidly changing world.

References

- The Life and Times of Franz Boas - JSTOR Daily. daily.jstor.org

- Boas Publishes The Mind of Primitive Man | EBSCO Research Starters. www.ebsco.com

|

|

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|