Social Movements

Index

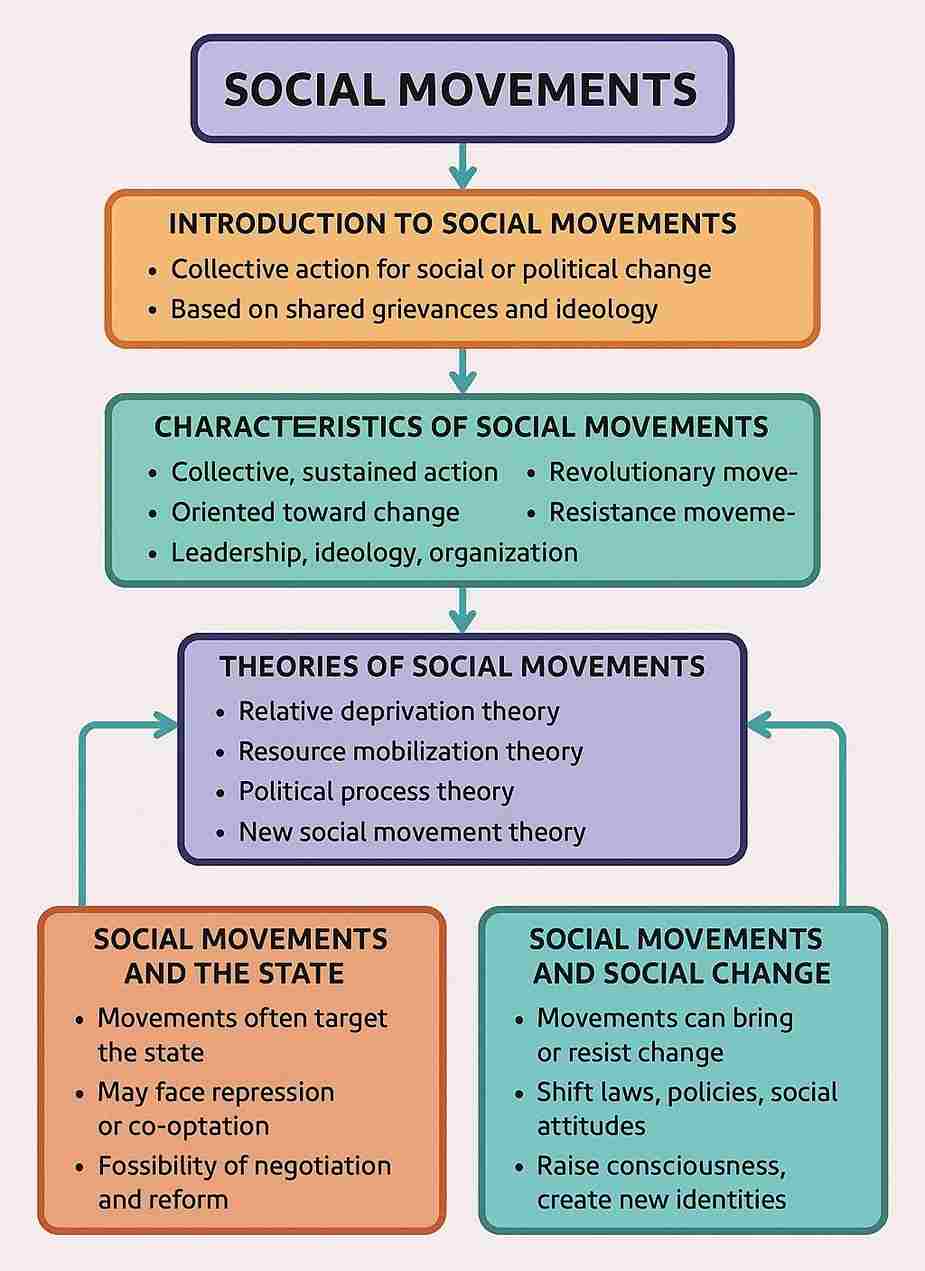

Introduction to Social Movements

Social movements are a powerful form of collective action through which groups of individuals express dissent, demand change, and seek to influence existing power relations. They arise when large numbers of people develop a shared consciousness about systemic injustice, inequality, or unfulfilled aspirations. Social movements are inherently political, in that they aim to change the distribution of power, resources, or cultural norms. Unlike isolated or spontaneous outbursts like riots or revolts, social movements are characterised by sustained efforts and strategic action over a period of time. Their emergence is often linked to structural tensions within society—such as class disparities, caste-based exclusion, gender oppression, or environmental degradation.

Historically, social movements have played a central role in shaping societies. In India, the anti-colonial freedom struggle itself was a wide-ranging social movement involving peasants, workers, students, women, and political leaders like Gandhi, Ambedkar, and Nehru. Globally, movements like the American Civil Rights Movement, the French Revolution, or the Arab Spring exemplify the transformative power of collective action. The study of social movements allows sociologists to explore how societies evolve, how individuals resist oppression, and how new forms of collective identity and political participation are forged.

Characteristics of Social Movements

Social movements possess distinct characteristics that differentiate them from other forms of collective behaviour. One of the most fundamental features is collective action. Movements are inherently group-based phenomena. Individual grievances alone do not constitute a movement; what matters is the formation of a shared sense of injustice and common goals among people. This collective consciousness is crucial to mobilising people around a cause. Another defining characteristic is that movements are sustained over time. While protests or demonstrations may be temporary, movements are typically long-term efforts that involve planning, campaigns, alliances, and often cycles of mobilisation and decline.

Movements are also oriented toward change—either to bring about new rights and reforms, resist ongoing change, or preserve and revive past traditions. This change could be social (e.g., challenging caste hierarchies), political (e.g., demanding state accountability), economic (e.g., opposing neoliberal reforms), or cultural (e.g., promoting indigenous identities). Social movements also operate both within and outside institutional frameworks. For example, a movement may engage with legal systems while also organising mass rallies or sit-ins. Leadership and organisation are crucial; charismatic leaders (like Gandhi or Medha Patkar) often serve as rallying points, but decentralised leadership models (like those in feminist or LGBTQ+ movements) also exist.

Finally, social movements have an ideological core—a belief system or worldview that legitimises their actions and defines their goals. For example, the Narmada Bachao Andolan was not just about displacement but also about challenging development paradigms that ignore ecological and human costs. Thus, movements are not just protests but sites of meaning-making, resistance, and identity formation.

Types of Social Movements

Sociologists have classified social movements based on the nature of change they seek, the extent of transformation they demand, and the methods they use. One common typology divides them into four main categories.

Reform movements aim for gradual and systematic changes within

the existing social and political order. They do not seek to

overthrow systems but rather to improve them. For instance, the

Indian environmental movement seeks better regulation and

sustainable development rather than rejecting industrialisation

altogether. Similarly, the movement for Right to Information (RTI)

was a reformist initiative that enhanced transparency in

government functioning through legal routes.

Revolutionary movements seek radical transformation and often

target the fundamental structures of state or society. These

movements may advocate violent means or armed struggle,

although not always. A prime example is the Naxalite movement,

which began in 1967 in Naxalbari, West Bengal, and called for the

overthrow of the Indian state in favour of a communist regime.

Revolutionary movements are driven by ideologies like Marxism or

Maoism and often mobilise marginalised groups, such as landless

labourers or tribal communities.

Resistance or reactionary movements arise in response to perceived

threats to cultural or social values. These movements often aim to

preserve traditional hierarchies or reverse progressive changes. For

example, the opposition to women’s entry into the Sabarimala

temple in Kerala can be seen as a resistance movement rooted in

cultural traditionalism. Similarly, far-right nationalist movements

that oppose immigration or minority rights often fall under this

category.

Utopian or expressive movements focus more on lifestyle changes,

spiritual awakening, or alternative communities rather than direct

political intervention. Movements like the Bhoodan Movement led

by Vinoba Bhave, which encouraged landowners to voluntarily

donate land to the landless, reflect a moral and spiritual dimension

rather than political struggle. Though often small in scale, such

movements can inspire broader changes in values and norms.

This typology highlights that not all social movements are

progressive. Some reinforce inequality or seek to maintain the

status quo. Understanding their nature helps us critically assess

their impacts on society.

Theories of Social Movements

Understanding why social movements emerge and how they sustain themselves has been a central concern for sociologists. Multiple theories have evolved to explain the causes, dynamics, and outcomes of social movements, each emphasizing different factors like emotion, resources, structure, and identity.

a) Relative Deprivation Theory

This theory suggests that social movements arise when individuals or groups feel that they are being unjustly deprived of something they believe they deserve—such as resources, rights, dignity, or recognition. Importantly, it is not objective poverty but perceived inequality that triggers unrest. For instance, the Dalit movement in India did not emerge solely from material deprivation, but from the realisation that caste-based discrimination violated human dignity and constitutional values. Similarly, the anti-Mandal agitation in the 1990s was a result of perceived deprivation among upper-caste youth regarding job reservations. However, this theory has been critiqued for being overly psychological and not explaining why only some groups mobilise despite widespread deprivation.

b) Resource Mobilisation Theory

This theory shifts the focus from grievances to organisational ability. It argues that movements succeed not because of how deprived people feel but because of how well they can mobilise and manage resources—funding, media support, skilled leaders, and organisational networks. For instance, the success of the India Against Corruption movement in 2011 (led by Anna Hazare) was due in part to its ability to attract media coverage, urban middle-class support, and digital outreach. This theory helps explain why some movements with fewer grievances succeed while others with deeper discontent fail.

c) Political Process Theory

This theory adds a structural dimension, suggesting that movements emerge when political opportunities are favourable. These may include divisions within the ruling class, state concessions, electoral openings, or increased media access. For example, the rise of the Dalit Panthers in Maharashtra in the 1970s was enabled by political instability and the availability of a democratic space for cultural assertion. Similarly, tribal movements like the Jharkhand Mukti Morcha gained momentum when regional aspirations found partial support among political parties seeking vote banks. Political process theory bridges agency and structure, emphasising that grievances alone do not lead to mobilisation unless the political climate is receptive.

Social Movements and the State

The relationship between social movements and the state is complex, often oscillating between confrontation, negotiation, and co-optation. On one hand, the state is often the primary target of social movements. Movements demand that the state recognise their grievances and enact reforms—be it legal protection, economic rights, or social recognition. On the other hand, the state may perceive movements as threats to order, unity, or development and respond with repression, surveillance, or delegitimisation.

In India, the Chipko Movement (1973) forced the state to revise forest policies after public protests in Uttarakhand where villagers hugged trees to prevent deforestation. In contrast, the Narmada Bachao Andolan, despite decades of resistance, faced repeated state crackdowns and was marginalised by the “development” narrative. The anti-CAA protests of 2019–2020 are another example where the state responded with both force and disinformation campaigns.

At times, the state co-opts movements by incorporating leaders into the political process, offering partial reforms, or diverting attention through bureaucratic hurdles. While this may lead to some gains, it can also weaken the radical edge of movements. Therefore, social movements often have to balance engagement and resistance, deciding whether to work within the system or challenge it from outside.

Major Social Movements in India

a) Peasant Movements

India has witnessed a series of peasant uprisings, driven by landlessness, indebtedness, unfair taxation, and feudal exploitation. In colonial times, the Indigo Revolt in Bengal (1859–60) and the Deccan Riots (1875) were expressions of rural resistance to oppressive landlords and colonial policy. Post-independence, the Telangana Rebellion (1946–51) involved armed peasant revolt against feudal landlords under the leadership of the Communist Party of India. More recently, the 2020–2021 farmers’ protest against three farm laws represented a massive, organised movement that pressured the Indian government to repeal the laws. These movements show how rural communities have continuously engaged with both class-based and policy-based issues through mobilisation.

b) Dalit Movements

The Dalit movement in India seeks to dismantle the deeply entrenched caste hierarchy and secure dignity, equality, and justice for historically oppressed castes. Inspired by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the movement has taken multiple forms—from political mobilisation (like the Bahujan Samaj Party) to cultural assertion (like Dalit literature, poetry, and music). Groups like the Dalit Panthers in Maharashtra in the 1970s adopted a militant tone, drawing inspiration from the Black Panthers in the U.S. and combining anti-caste and class critique. The movement has succeeded in placing caste-based violence, reservation, and dignity politics at the heart of Indian democracy.

c) Tribal Movements

Tribal or Adivasi movements revolve around land alienation, cultural erasure, forest displacement, and resistance to extractive development. The Santhal Rebellion (1855) and the Birsa Munda Uprising (1895–1900) were early tribal assertions against colonial and feudal domination. Post-independence, movements like the Jharkhand Mukti Morcha (JMM) demanded separate statehood, which they eventually achieved in 2000. The Dongria Kondh tribe’s resistance to mining by Vedanta in Odisha, supported by environmentalists, exemplies how tribal movements now intersect with ecological and indigenous rights discourse.

d) Women’s Movements

India’s women’s movement has evolved from social reform in the colonial period (e.g., campaigns against sati and child marriage) to contemporary struggles around violence, rights, sexuality, and representation. In the 1970s, the movement re-emerged with cases like the Mathura rape case, which led to amendments in Indian rape law. Organisations like SEWA (Self-Employed Women’s Association) combine gender and labour rights. Feminist movements have also critiqued patriarchy within families, workplaces, and even within other social movements. Today, movements like #MeToo and protests against gender-based violence are reshaping digital and legal spaces alike.

e) Environmental Movements

India’s environmental movements reflect resistance to state-corporate development models that ignore ecological sustainability and community rights. The Chipko Movement (1973) pioneered the idea of non-violent eco-resistance by villagers hugging trees to prevent deforestation. The Narmada Bachao Andolan, led by Medha Patkar, opposed the construction of the Sardar Sarovar Dam, highlighting displacement and ecological harm. These movements connect local struggles to global debates on development, equity, and climate change, showing how the environment is deeply political.

f) Students’ Movements

Students have played a pivotal role in Indian political life. The JP Movement (1974–75) mobilised students across North India against corruption and authoritarianism, eventually leading to the Emergency. In recent years, campuses like JNU, AMU, and HCU have become sites of resistance to caste discrimination, saffronisation, and authoritarian governance. Student groups have protested fee hikes, sedition charges, and institutional violence (like the death of Rohith Vemula). These movements combine youthful energy with ideological clarity, often becoming the vanguard of wider democratic struggles.

Challenges Faced by Social Movements

Despite their transformative potential, social movements face

numerous and multifaceted challenges that threaten their

momentum, legitimacy, and sustainability. One of the foremost

challenges is state repression. Governments—especially when

authoritarian or corporatist in nature—often respond to movements

with tactics like police violence, mass arrests, internet shutdowns,

surveillance, and the invocation of sedition or anti-terror laws. For

example, the anti-CAA protests in India saw widespread detentions

and internet bans, particularly in regions like Assam and Uttar

Pradesh. Similarly, tribal rights activists and anti-mining protestors

have frequently been charged under laws like the Unlawful

Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), despite peaceful mobilisation.

Another challenge is internal fragmentation within movements.

Movements are not homogenous; they often include people of

different ideologies, classes, castes, genders, and political

affiliations. This diversity, while enriching, can also lead to

conicts. For instance, the mainstream feminist movement in India

has been critiqued by Dalit and Adivasi women for failing to

address their specic concerns, giving rise to intersectional

feminism as a corrective framework. Similarly, peasant movements

have at times failed to acknowledge gender roles in agriculture or

the unique challenges of tenant farmers and landless labourers.

Media representation is another obstacle. While traditional media

can amplify a movement’s message, it can also distort or

delegitimise it. Movements are often labelled as “anti-national,”

“urban naxals,” or “foreign-funded,” especially when they

challenge dominant ideologies or powerful interests. The portrayal

of the Shaheen Bagh protestors as either heroic or anti-national

across different media platforms is a clear example of how the same

movement can be framed in vastly different ways, impacting public

support.

Co-optation is yet another challenge, particularly in democratic

contexts. Sometimes the state or corporate sector may absorb

movement leaders into advisory positions, dilute demands through

symbolic gestures, or introduce partial reforms that pacify

momentum without altering core structures. For example, the Right

to Education Act was celebrated as a victory for educational

activists, but its poor implementation has led to criticism that the

movement was defanged once its legal demand was met.

Lastly, the rise of digital surveillance and algorithmic

suppression—such as shadow-banning, platform censorship, and

online trolling—has added new layers of difficulty for modern

movements. While digital platforms have opened new spaces for

activism, they are also subject to manipulation and control, making

sustained mobilisation challenging.

Conclusion

Social movements are indispensable to the functioning and

evolution of any vibrant democracy. They represent the collective

aspirations, frustrations, and imaginations of ordinary people

seeking justice, recognition, and dignity. While they may not

always succeed in achieving their immediate objectives, their

broader contributions to consciousness-raising, rights discourse,

and institutional reform are profound and enduring. In India, from

anti-caste struggles to environmental activism, and from peasant

protests to feminist mobilisations, social movements have

consistently challenged state apathy, market excesses, and societal

prejudice.

Their strength lies not only in numbers but in their ability to build

solidarity across difference, articulate alternative visions, and

pressure institutions to respond to the needs of the marginalised.

However, movements must remain vigilant against co-optation,

fragmentation, and repression. They must also continue evolving to

address contemporary issues—be it climate change, digital

surveillance, or global inequality.

In essence, social movements are not just about opposition—they

are about proposing new ways of living, governing, and relating to

one another. They are living testimonies to the belief that another

world is possible, and that history is not only made by rulers and

policies, but by the collective will of people rising in hope and

resistance.

References

- Shah, Ghanshyam (2002). Social Movements in India: A Review of Literature. Sage Publications.

- Tarrow, Sidney (1998). Power in Movement: Social Movements and Contentious Politics. Cambridge University Press.

- Oommen, T.K. (1990). Protest and Change: Studies in Social Movements. Sage Publications.

- Omvedt, Gail (1993). Reinventing Revolution: New Social Movements and the Socialist Tradition in India. M.E. Sharpe.

|

|

In a society a large number of changes have been brought about by efforts exerted by people individually and collectively. Such efforts have been called social movements. A social movement is defined as a collectively acting with some continuity to promote or resist a change in the society or group of which it is a part. Social movement is a form of dynamic pluralistic behavior that progressively develops structure through time and aims at partial or complete modification of the social order. A social movement may also be directed to resist a change. Some movements are directed to modify certain aspects of the existing social order whereas others may aim to change it completely. The former are called reform movements and the latter are called revolutionary movements. Social movements may be of numerous kinds such as religious movements, reform movements or revolutionary movements. Lundberg defined social movement as a voluntary association of people engaged in concerted efforts to change attitudes, behavior and social relationships in a larger society.

Main features of social movement may be

It is an effort by a group.

Its aim is to bring or resist a change in society

It may be organized or unorganized.

It may be peaceful or violent

Its life is not certain. It may continue for a long period or may die out soon.

Reform Movements

1. Arya Samaj

Main principals of Arya Samaj

2. Satya Sodhak Samaj

Main Principles of Satya Sodhak Samaj

3. Ram Krishna Mission

Main principles of Shri Rama Krishna Paramahansa

4. Sri Narayanguru Dharma Paripalana Sabha

Peasant Movements

Backward Castes Movement

1. Self -respect Movement

2. Backward caste mobilization in North India

1. Mahar Movement

Middle Class Movements

Nativist Movement

Indian Environment Movement

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|

Social Movements and Social Change

The primary goal of social movements is to bring about or resist social change. This change can be tangible—such as new laws, policies, or institutions—or intangible, like shifts in values, language, and cultural attitudes. Even when movements do not achieve their immediate goals, they often transform the way people think, speak, and act. For instance, the women’s movement in India has made sexual harassment, domestic violence, and reproductive rights mainstream topics in law, media, and education.

Movements contribute to democratisation by holding power accountable and giving voice to the marginalised. The Right to Information movement, which began as a local initiative in Rajasthan, led to national legislation in 2005 that fundamentally altered how citizens engage with governance. Similarly, the Bharatiya Kisan Union (BKU) and other farmer organisations have reshaped agricultural policy debates through sustained protests and dialogues.

Social movements also foster new identities. They enable people to move from being isolated victims to conscious actors. For example, the Dalit movement gave a name, history, and pride to oppressed castes who were earlier socially excluded. Through songs, literature, public events, and legal activism, movements redene who people are and what they can aspire to. In this way, movements are not only political events but cultural revolutions.