Home » Social Thinkers » C.H Cooley

C.H Cooley

Index

Introduction

Charles Horton Cooley was born on August 17, 1864, in Ann Arbor, Michigan, to Mary Elizabeth Horton and Thomas McIntyre Cooley, a distinguished jurist and the first dean of the University of Michigan Law School. Growing up in an intellectually stimulating environment, Cooley developed a keen interest in social sciences, despite initial health challenges that delayed his academic progress. He earned his undergraduate degree in mechanical engineering in 1887 and later a Ph.D. in sociology in 1894 from the University of Michigan, where he taught economics and sociology until his death in 1929. A founding member of the American Sociological Association and its eighth president in 1918, Cooley’s work focused on the interplay between individual consciousness and social structures. His introspective and literary approach, combined with his rejection of rigid individualism and mechanical social theories, positioned him as a unique figure in early American sociology. Cooley’s legacy endures through his foundational contributions to understanding how social interactions shape the self and society.

Intellectual Background

Cooley’s intellectual development was shaped by a blend of philosophical and sociological influences. He was deeply influenced by American transcendentalism, particularly the works of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson, which emphasized individual intuition and the organic unity of human experience. The pragmatism of William James and John Dewey also played a significant role, particularly James’s concept of the self, which Cooley expanded in his own theories. Additionally, Cooley drew from the sociology of Herbert Spencer, though he rejected Spencer’s mechanistic evolutionism in favor of a more humanistic and organic view of society. The German economist and sociologist Albert Schäffle inspired Cooley’s ideas about communication as a central mechanism of social organization. Cooley’s religious beliefs, reflected in his journal entry “nulla linea sine Deo” (no single line without God), underscored his view of sociology as a moral and spiritual endeavor. His academic environment at the University of Michigan, where he interacted with scholars like George Herbert Mead, further shaped his focus on social psychology and the relational nature of human life. Despite personal challenges, including partial deafness and a speech impediment, Cooley’s introspective approach and commitment to the essay tradition allowed him to develop a distinctive sociological perspective that prioritized subjective experience and social interconnectedness.

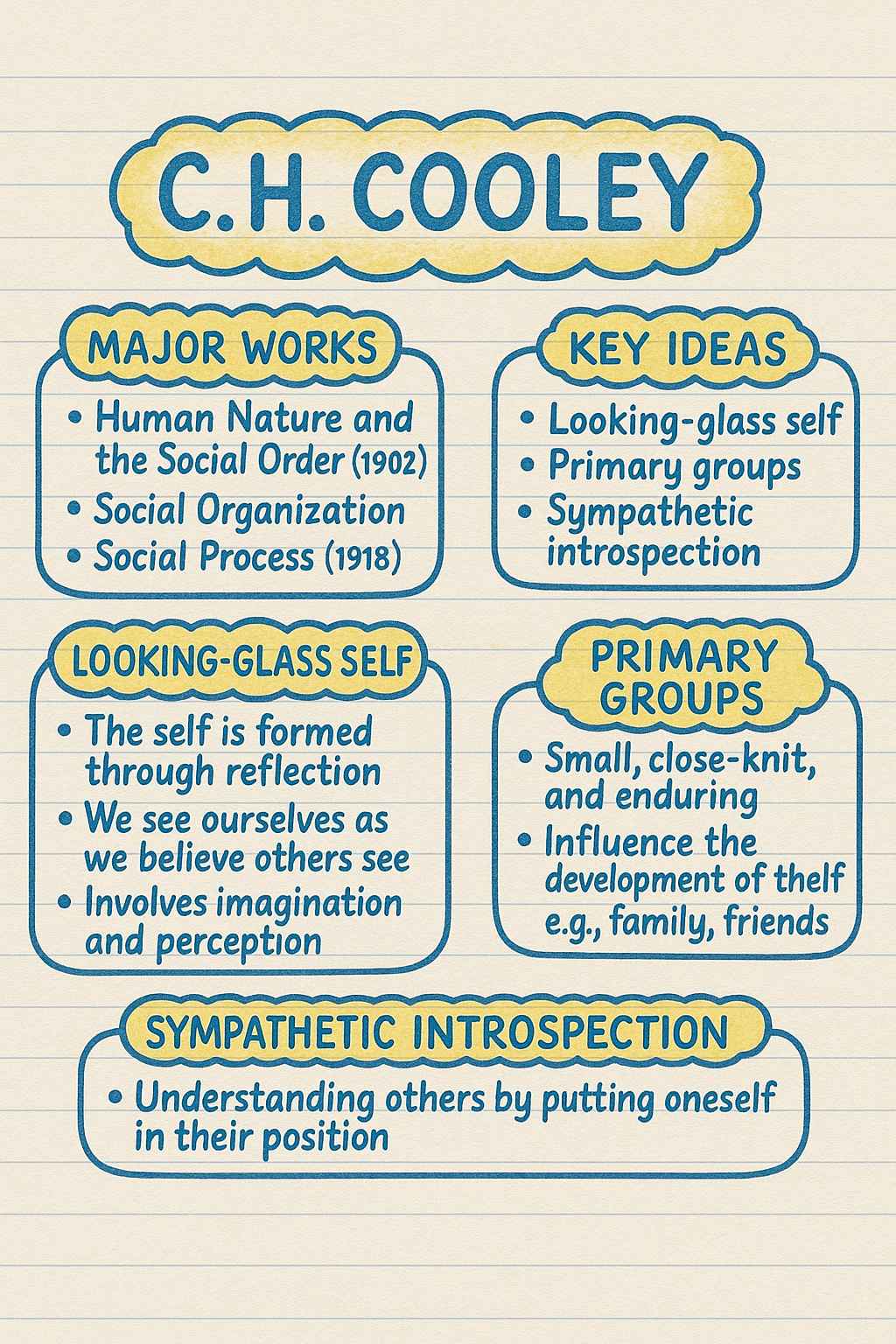

Key Ideas and Concepts

Cooley’s sociological contributions revolve around two central concepts: the “looking-glass self” and the “primary group,” both of which underscore the social nature of human identity and behavior. The looking-glass self, introduced in Human Nature and the Social Order (1902), posits that an individual’s self-concept is formed through social interactions, specifically by imagining how one appears to others, interpreting their judgments, and developing feelings such as pride or shame based on those perceptions. This three-step process highlights the reflective nature of identity, where the self is a social construct shaped by perceived external evaluations. Cooley argued that this process begins in childhood and continues throughout life, emphasizing that humans are inherently social beings whose identities are inseparable from their interactions.

The primary group, detailed in Social Organization (1909), refers to small, intimate, face-to-face groups like families, neighborhoods, or children’s play groups that are fundamental in shaping an individual’s social nature, morals, and ideals. Cooley described these groups as characterized by a sense of “we-ness,” where individuals experience a fusion of identities and develop values such as loyalty, kindness, and justice. He believed primary groups serve as the foundation for social cohesion and the transmission of universal human values, which he termed “primary ideals.” These ideals, rooted in direct communication and cooperation, influence broader societal structures, including democratic institutions. Cooley also introduced the concept of the social self, arguing that individual identity is inseparable from social relations, rejecting the utilitarian notion of an autonomous self and the deterministic view of a fully socially controlled individual. He saw society and the individual as interdependent, with communication acting as the bridge between personal consciousness and collective life. Additionally, Cooley’s notion of the social mind suggested that society operates as an organic whole, akin to an orchestra, where individual minds contribute to a collective consciousness through shared meanings and interactions.

Major Works and Explanations

Cooley’s most influential works form a trilogy that systematically develops his sociological perspective: Human Nature and the Social Order (1902), Social Organization (1909), and Social Process (1918). Additionally, Sociological Theory and Social Research (1930), a posthumous collection of his papers, and Life and the Student (1927) provide further insights into his thought.

- Human Nature and the Social Order (1902): This foundational work explores the development of the self through social interactions, introducing the concept of the looking-glass self. Cooley argued that the self is not a fixed entity but a dynamic product of social processes, shaped by how individuals perceive others’ views of them. Drawing from empirical observations of his own children and literary references from Shakespeare, Goethe, and others, Cooley examined how the self encompasses values, ideas, and social roles beyond the physical body. He posited that human nature is not merely biological but emerges from intimate social contacts, particularly in primary groups. The book challenges Cartesian dualisms by emphasizing the interconnectedness of mind and society, laying the groundwork for symbolic interactionism

- Social Organization: A Study of the Larger Mind (1909): In this work, Cooley expands on the role of primary groups in shaping social values and institutions. He argues that primary groups are the cradle of human nature, fostering ideals like loyalty and freedom that underpin democratic societies. The book contrasts primary groups with larger, more impersonal “nucleated” (later called secondary) groups, such as trade unions or political parties, which lack the same intimacy. Cooley also explores how communication and deliberation within primary groups influence public opinion and social order, viewing democracy as a reflection of primary group values. The first 60 pages of the book critique Freud’s individualistic psychoanalysis, emphasizing the social origins of morality and identity.

- Social Process (1918): This work focuses on the dynamic nature of social change and the role of communication in adapting to new societal challenges. Cooley examines how social disorganization, such as economic inequality or institutional rigidity, can lead to opportunities for “adaptive innovation.” He advocates for deliberative communication to maintain social cohesion and argues that social classes are a normal part of democracy, provided they engage in open debate. The book applies Darwinian principles of natural selection to social processes, suggesting that societies evolve through interaction and adaptation.

Critics and Limitations

While Cooley’s work was groundbreaking, it faced criticism for its idealistic and subjective approach. Critics, including George Herbert Mead, argued that Cooley overemphasized the individual’s mental processes at the expense of social structures and power dynamics. Mead’s posthumous critique suggested that Cooley’s focus on the looking-glass self and primary groups neglected the broader institutional constraints that shape behavior, leading to an incomplete view of society. Some scholars, such as those cited in Encyclopedia.com, noted that Cooley’s conception of society as a mental construct overlooked the role of “crude power” and structural inequalities, presenting an idealized model rather than a comprehensive one. His empirical work, while innovative for its time, was limited by its reliance on introspection and observations of his own children, lacking the rigorous methodologies favored by positivist sociologists. Additionally, Cooley’s concept of the looking-glass self has been criticized for its focus on ingroup appraisals, potentially ignoring how outgroup perceptions influence identity. Critics also pointed out that his romantic view of primary groups and democracy understated the conflicts and divisions within societies. Despite these critiques, Cooley’s ideas have been recognized for their originality and their influence on symbolic interactionism, though some argue his work was overshadowed by Mead’s more systematic theories.

Contemporary Relevance

Cooley’s concepts remain highly relevant in contemporary sociology, particularly in the fields of social psychology, symbolic interactionism, and digital culture. The looking-glass self has been widely applied to understand identity formation in the digital age, where social media platforms amplify the role of perceived external judgments. For instance, Mary Aiken’s concept of the “cyber self” builds on Cooley’s theory, highlighting how individuals craft online identities based on feedback from digital interactions. Studies, such as those by Kondrat and Teater (2012), have applied the looking-glass self to mental health recovery, showing how positive perceptions from caregivers can foster healthier self-concepts among individuals with severe mental illness. Cooley’s emphasis on primary groups resonates in research on social cohesion, community resilience, and the role of family and peer networks in shaping behavior. His ideas about communication and deliberation inform contemporary studies of democratic processes and public opinion formation, particularly in the context of polarized digital discourse. Books like Updating Charles H. Cooley (2018) highlight his influence on modern sociological debates about emotions, digital culture, and inequality in imagined communities. While some aspects of his work, such as his idealistic view of democracy, may seem dated, Cooley’s focus on the social self and the organic nature of society continues to inspire research on identity, socialization, and the interplay between individual agency and social structures.

References

- Routledge. (2020). Updating Charles H. Cooley: Contemporary Perspectives on a Sociological Classic.

- Lesley University. (n.d.). Perception Is Reality: The Looking-Glass Self.

- American Sociological Association. (2009). Charles H. Cooley.

- Simply Psychology. (2023). Looking-Glass Self: Theory, Definition & Examples.

- Wikipedia. (2006). Looking-glass self.

|

|

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|