Home » Social Thinkers » Sir Edward Evans Pritchard

Sir Edward Evans Pritchard

Index

Introduction

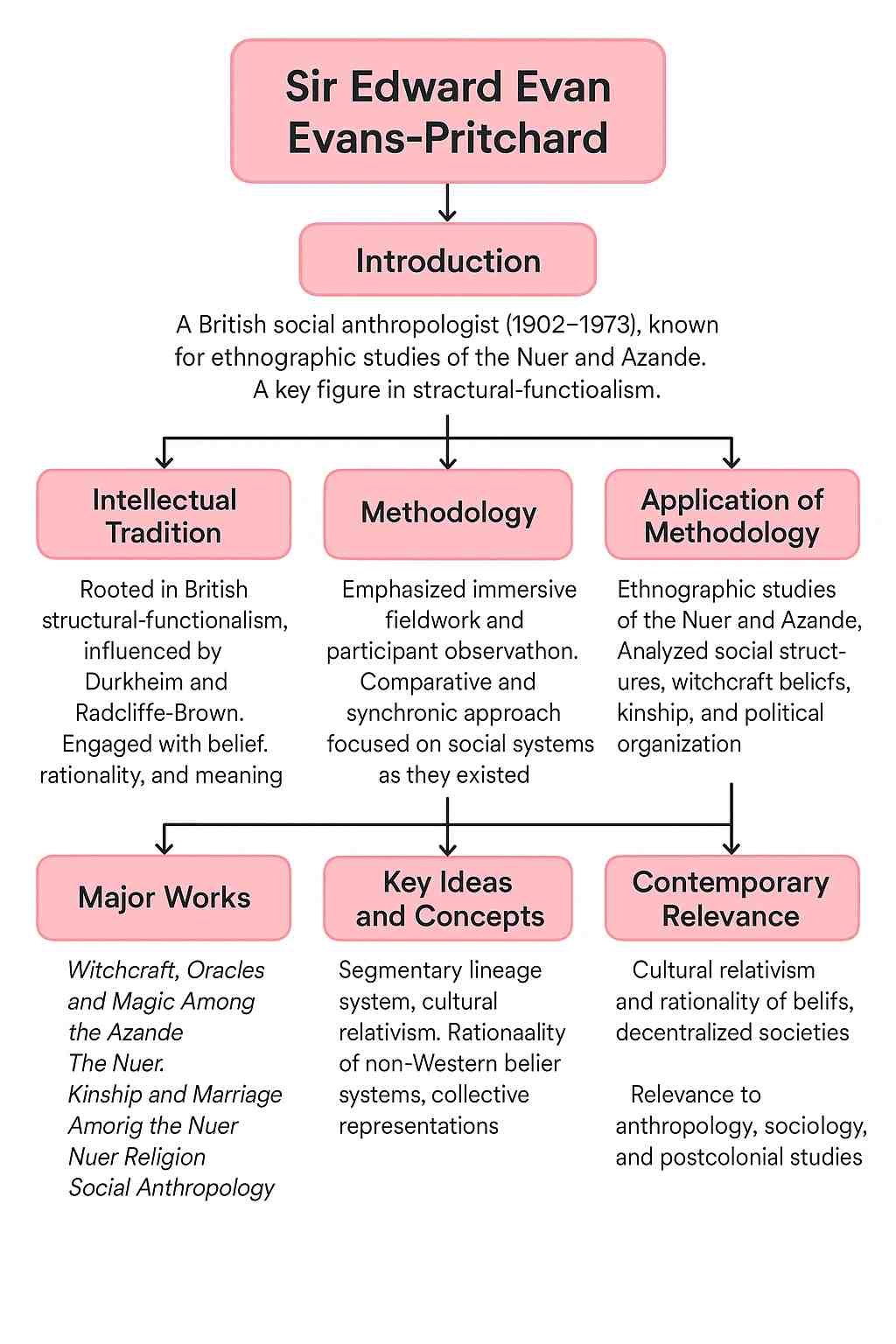

Sir Edward Evan Evans-Pritchard (1902–1973) was a towering figure in British social anthropology, renowned for his ethnographic studies of African societies, particularly the Nuer and Azande. Born in Sussex, England, he studied at Oxford University under R.R. Marett and later at the London School of Economics under Bronisław Malinowski and Charles Gabriel Seligman. Evans-Pritchard’s work bridged anthropology and sociology, emphasizing the importance of understanding social structures and cultural practices within their specific contexts. His fieldwork, primarily conducted in the 1920s and 1930s in what is now South Sudan and the Congo, established him as a pioneer in ethnographic methods. He held the prestigious position of Professor of Social Anthropology at Oxford from 1946 to 1970, shaping the discipline through his rigorous empirical approach and theoretical contributions. His work moved away from the speculative evolutionism of earlier anthropologists, focusing instead on synchronic analyses of social systems and their functional interrelations, making him a key figure in structural-functionalism.

Intellectual Tradition

Evans-Pritchard was deeply rooted in the British structural-functionalist tradition, which dominated social anthropology in the early 20th century. Influenced by Émile Durkheim’s sociological ideas, particularly the notion of society as a system of interrelated parts, he adopted a functionalist lens to study how social institutions maintain societal cohesion. His training under Malinowski introduced him to the importance of intensive fieldwork and participant observation, though he diverged from Malinowski’s psychological functionalism, which focused on individual needs. Instead, Evans-Pritchard aligned more closely with A.R. Radcliffe-Brown’s structural-functionalism, emphasizing social structures and their role in maintaining social order. However, he was not a rigid functionalist; his later works incorporated historical and comparative perspectives, reflecting a nuanced approach that acknowledged cultural specificity and change. His intellectual tradition also engaged with philosophical questions about belief, rationality, and meaning, particularly in his studies of religion and magic, positioning him as a bridge between anthropology and broader humanistic disciplines.

Methodology

Evans-Pritchard’s methodology was grounded in immersive, long-term fieldwork, which he saw as essential for understanding the complexities of social life. He advocated for participant observation, living among the people he studied to grasp their worldview and social practices firsthand. His approach was holistic, aiming to capture the interconnectedness of social, cultural, and economic systems within a society. Unlike purely theoretical or armchair anthropology, his method emphasized empirical data collection through detailed observation, interviews, and documentation of daily life. He stressed the importance of learning local languages to access unfiltered perspectives, as seen in his work with the Nuer and Azande. Evans-Pritchard also employed a comparative method, analyzing similarities and differences across societies to highlight universal social principles and cultural variations. His methodology was synchronic, focusing on societies as they existed at the time of study, though he later incorporated historical contexts to address criticisms of ahistoricism in functionalism.

Application of Methodology

Evans-Pritchard’s methodology was vividly applied in his ethnographic studies of the Nuer and Azande. Among the Nuer of South Sudan, he lived for extended periods between 1930 and 1936, learning their language and participating in their daily activities to understand their segmentary lineage system and political organization. His immersive approach allowed him to document the Nuer’s acephalous (headless) society, where social order emerged without centralized authority, challenging Western assumptions about governance. Similarly, his study of the Azande, conducted in the late 1920s, focused on their beliefs in witchcraft and oracles. By engaging directly with Azande informants and observing their rituals, he provided a nuanced account of how witchcraft functioned as a logical system of explanation within their cultural framework. His comparative method was evident in his analysis of kinship, religion, and political systems across these groups, highlighting how social structures adapted to specific environmental and historical contexts. His meticulous field notes and emphasis on emic perspectives (the insider’s view) set a standard for ethnographic rigor

Major Works

Evans-Pritchard’s prolific career produced several seminal works that remain foundational in anthropology and sociology. His most influential book, Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic Among the Azande (1937), explored Azande beliefs in witchcraft as a coherent system of thought, challenging Western notions of rationality. The Nuer: A Description of the Modes of Livelihood and Political Institutions of a Nilotic People (1940) provided a detailed analysis of the Nuer’s segmentary lineage system and their adaptation to environmental constraints. Kinship and Marriage Among the Nuer (1951) further elaborated on Nuer social organization, focusing on family structures. Nuer Religion (1956) examined the spiritual beliefs of the Nuer, emphasizing their concept of kwoth (spirit) and its role in social cohesion. His theoretical work, Social Anthropology (1951), outlined his views on the discipline’s scope and methods, advocating for anthropology as a comparative social science. Additionally, Essays in Social Anthropology (1962) and Theories of Primitive Religion (1965) synthesized his ideas on religion, social structure, and anthropological theory, influencing generations of scholars.

Key Ideas and Concepts

Evans-Pritchard’s key ideas revolve around social structure, cultural relativism, and the rationality of non-Western belief systems. His concept of the segmentary lineage system, developed through his Nuer studies, describes how societies without centralized authority maintain order through balanced oppositions between kinship groups. This idea challenged Eurocentric views of political organization and highlighted the complexity of acephalous societies. In Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic, he introduced the notion that witchcraft beliefs are not irrational but form a logical framework for explaining misfortune, demonstrating cultural relativism. His concept of collective representations, inspired by Durkheim, emphasized how shared beliefs and rituals reinforce social cohesion. Evans-Pritchard also pioneered the study of religion as a social institution, arguing that religious beliefs reflect and sustain social structures. His later work emphasized the importance of historical context and cultural specificity, moving beyond strict functionalism to acknowledge change and agency in social systems.

Critiques

While Evans-Pritchard’s contributions are monumental, his work has faced several critiques. One major criticism is the ahistorical nature of his early functionalist analyses, particularly in The Nuer, where he focused on synchronic social structures, largely ignoring historical processes and colonial influences. Critics argue this approach risks presenting societies as static and unchanging. His methodology, while rigorous, has been critiqued for its reliance on the anthropologist’s subjective interpretation, raising questions about objectivity in ethnographic accounts. Some postcolonial scholars have pointed out that his work, conducted under British colonial administration, may reflect colonial biases, particularly in its portrayal of African societies as “primitive.” Additionally, his focus on social structures has been seen as neglecting individual agency and internal diversity within societies. Feminist anthropologists have noted the limited attention to gender dynamics in his studies, particularly in kinship analyses. Despite these critiques, his work remains a benchmark for ethnographic depth and theoretical innovation.

Contemporary Relevance

Evans-Pritchard’s work continues to resonate in contemporary sociology and anthropology. His emphasis on cultural relativism remains crucial in an era of globalization, where understanding diverse worldviews is essential for cross-cultural dialogue. His concept of the segmentary lineage system informs studies of decentralized societies and conflict resolution in modern contexts, such as tribal governance in Africa and the Middle East. His insights into witchcraft and belief systems are relevant to studies of religion, superstition, and alternative epistemologies in both traditional and modern societies. The methodological rigor of his fieldwork serves as a model for qualitative research in sociology, particularly in ethnographic studies of marginalized communities. However, contemporary scholars build on his work by incorporating postcolonial and feminist perspectives, addressing his blind spots on gender and colonial power dynamics. His legacy also endures in debates about rationality and cultural difference, influencing disciplines like anthropology, sociology, and religious studies in addressing how societies construct meaning and maintain social order.

References:

- Evans-Pritchard, E. E. (1937). Witchcraft, oracles and magic among the Azande. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Kuper, A. (1983). Anthropology and anthropologists: The modern British school (3rd ed.). London: Routledge.

|

|

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|