Post Structuralism

Index

Introduction to Post-Structuralism

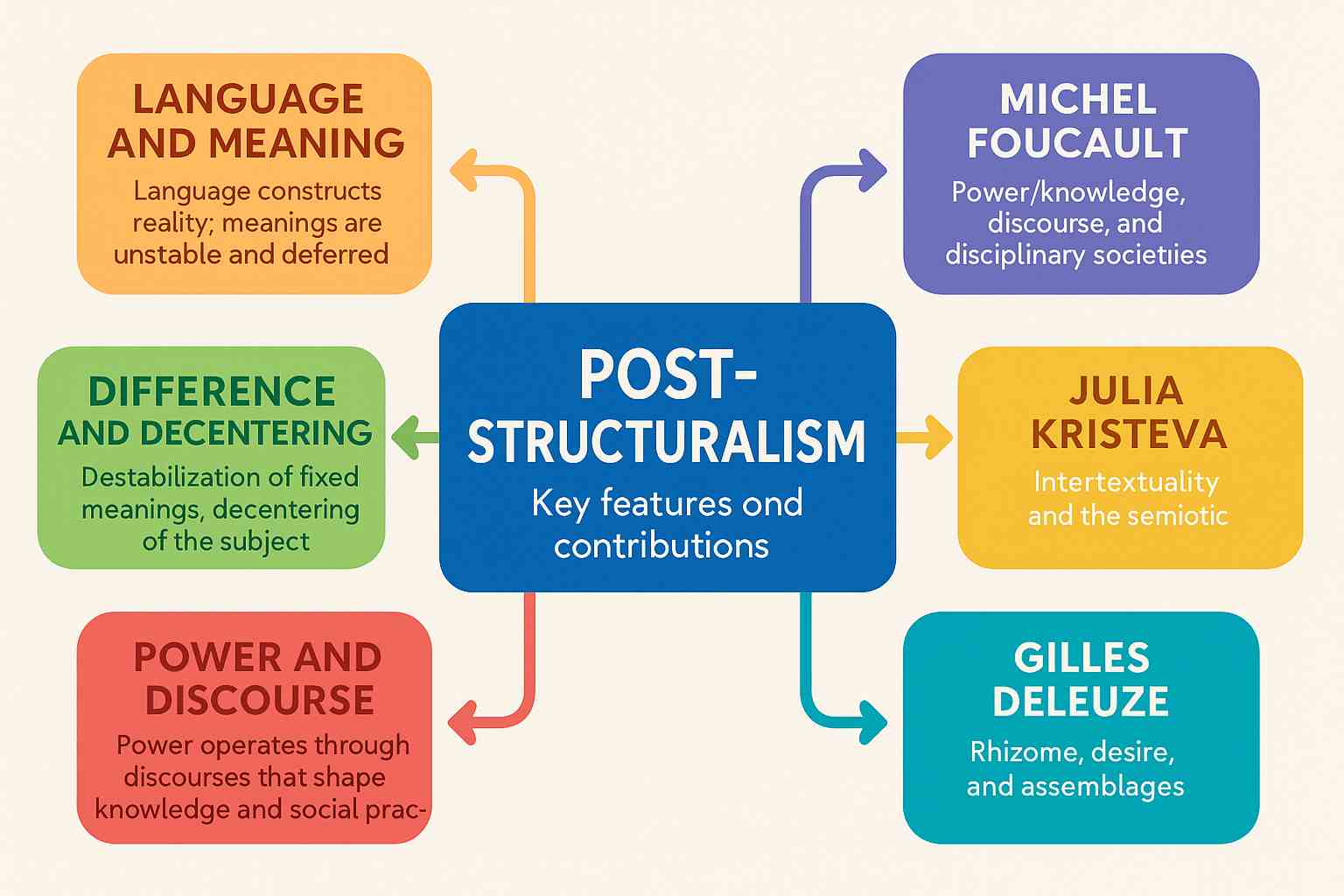

Post-Structuralism is a complex, multifaceted intellectual movement that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s as a critical response to Structuralism. While Structuralism emphasized underlying structures—particularly in language, culture, and society—Post-Structuralism questioned the stability, coherence, and universality of such structures. Post-Structuralism does not offer a singular or unified doctrine; rather, it encompasses a wide range of thinkers and approaches that share a skepticism toward grand narratives, fixed meanings, and essential truths. Instead, it promotes an understanding of the world as inherently fragmented, contingent, and constructed through language and power relations. Post-Structuralists argue that knowledge is not objective or neutral but is deeply embedded in socio-political contexts and shaped by discourses that regulate what can be known and said.

Historical Context and Emergence

Post-Structuralism emerged primarily in France during a period of intense political, cultural, and intellectual upheaval. The aftermath of World War II, the Algerian War, and the May 1968 student protests influenced French intellectuals to question Enlightenment ideals of rationality, progress, and universal humanism. Structuralism—dominant in the 1950s and early 1960s through the work of Claude Lévi-Strauss, Ferdinand de Saussure, and Roland Barthes—provided the analytical lens for understanding culture as governed by deep, systematic structures. However, thinkers like Foucault, Derrida, Kristeva, and Deleuze found Structuralism too rigid and deterministic, neglecting the instability of meaning, the contingency of knowledge, and the role of power. Post-Structuralism thus arose not in outright opposition to Structuralism, but as a deepened critique of its assumptions, challenging the idea of fixed structures and embracing difference, multiplicity, and fluidity.

Key Concepts in Post-Structuralism

Language, Meaning, and Displacement

Central to Post-Structuralism is the idea that language does not transparently represent reality but rather constructs it. Drawing from Saussure’s notion that meaning is produced through the difference between signs, Post-Structuralists argue that this difference is never stable. Jacques Derrida’s concept of différance illustrates that meaning is always deferred—constantly shifting in context and never fully present. Words gain significance not through intrinsic essence but through their relational position within a linguistic system. This challenges the assumption of objective truths or singular interpretations, positioning language as inherently unstable, metaphorical, and open-ended.

Power, Knowledge, and Discourse

Michel Foucault’s reconceptualization of power and knowledge marked a decisive shift in social theory. He argued that knowledge is not independent of power but is shaped by and reproduces it. Discourses—systems of language and knowledge—regulate what is considered true, normal, or deviant. Through mechanisms such as surveillance, normalization, and discipline, societies control bodies and behaviors. Institutions like prisons, schools, hospitals, and asylums operate not just through coercion but through subtle forms of governance embedded in discourse. Power, for Foucault, is not centralized or repressive, but productive—it produces identities, categories, and truths

Key Thinkers and Their Contributions

Michel Foucault: Power/Knowledge and Disciplinary Societies

Michel Foucault (1926–1984) stands as a central figure in Post-Structuralist thought. His work traversed multiple disciplines, including history, philosophy, medicine, and criminology. In Discipline and Punish (1975), he traced the historical transformation of punishment from spectacular public executions to the internalization of discipline within modern institutions. Foucault introduced the idea of panopticism—a form of surveillance where individuals police their own behavior, thereby reinforcing social norms. In The History of Sexuality (1976), he challenged the notion that sexuality was repressed in modern society, arguing instead that sexuality was continuously produced and regulated through discourse. Foucault’s concept of biopower—the regulation of populations through state mechanisms—remains foundational for understanding governance, public health, and modern capitalism.

Jacques Derrida: Deconstruction and Différance

Jacques Derrida (1930–2004) revolutionized literary theory and philosophy with his method of deconstruction. Deconstruction is not merely a negative critique but an effort to reveal the contradictions and instabilities within texts. In Of Grammatology (1967), Derrida deconstructs the binary opposition between speech and writing, arguing that Western philosophy privileges speech as more authentic. He introduces différance, a term that plays on the dual meaning of “difference” and “deferral,” to emphasize that meaning is never fixed but always postponed. Derrida insists that language is haunted by what it excludes—every text contains the seeds of its own undoing. His work has had a profound impact on literary criticism, legal studies, architecture, and theology.

Julia Kristeva: Intertextuality and the Semiotic

Julia Kristeva, a Bulgarian-French theorist, contributed significantly to psychoanalysis, linguistics, and feminism. She introduced the concept of intertextuality, which suggests that texts are not isolated entities but are always connected to other texts and cultural discourses. In Revolution in Poetic Language (1974), she proposed a distinction between the semiotic and the symbolic. The semiotic is linked to bodily drives, rhythms, and pre-linguistic experience, often associated with poetry and creativity, while the symbolic relates to structured language and social order. Kristeva’s fusion of Lacanian psychoanalysis with Post-Structuralism allows for a dynamic understanding of subjectivity, especially in relation to gender and marginality.

Gilles Deleuze: Rhizome, Desire, and Assemblages

Gilles Deleuze (1925–1995), often in collaboration with Félix Guattari, challenged traditional notions of identity, hierarchy, and causality. In A Thousand Plateaus (1980), they proposed the concept of the rhizome—a non-hierarchical, networked system of knowledge and being that resists linearity and centralization. Unlike trees with roots and branches, rhizomes spread horizontally and unpredictably. Deleuze and Guattari’s theory of desire moves away from Freudian lack toward a productive force that drives social formations. Their concept of assemblages suggests that reality is composed of constantly shifting connections—between bodies, technologies, discourses, and institutions. These ideas have been influential in fields like anthropology, architecture, media studies, and ecology.

Jean Baudrillard: Simulacra and Hyperreality

Jean Baudrillard (1929–2007) developed a unique critique of postmodern culture. In Simulacra and Simulation (1981), he argued that contemporary society is dominated by simulacra—representations that no longer refer to any real object but simulate simulations. This leads to hyperreality, where distinctions between reality and representation collapse. For example, media coverage of events often becomes more real than the events themselves. Disneyland, reality TV, and even political campaigns function as hyperreal constructs. Baudrillard’s vision is deeply pessimistic—he sees postmodern life as devoid of meaning, where images substitute for substance, and where the spectacle has replaced the social.

Jacques Lacan: Psychoanalysis Rewritten

Jacques Lacan, a French psychoanalyst, brought a significant psychoanalytic dimension to post-structuralist thought by reinterpreting the works of Sigmund Freud through the lens of language and structuralism. His famous dictum, “the unconscious is structured like a language,” was a major departure from traditional Freudian ideas. Lacan argued that the subject is not a coherent, autonomous self but a fragmented being constituted through language and symbolic systems.

According to Lacan, human identity is formed in stages, particularly through the “mirror stage,” where the infant identifies with its image in the mirror but remains separate from it. This results in a fundamental alienation, where the self is always chasing an unattainable wholeness. The symbolic order—largely governed by language—imposes structures that dictate meaning and subjectivity. Lacan’s concept of the “Other” highlights how individuals internalize and are shaped by social structures beyond their control.

Lacan’s emphasis on language, desire, and the instability of the subject deeply influenced feminist theorists like Julia Kristeva and post-structuralists like Žižek. He illuminated how deeply embedded systems of meaning (like language or ideology) influence our unconscious desires and ultimately control behavior and social relationships. Thus, he reconfigured psychoanalysis as not just therapeutic but as a critical tool to deconstruct identity, society, and even literature.

Roland Barthes: The Death of the Author

Roland Barthes played a pivotal role in bridging structuralism and post-structuralism. In his early works like Mythologies, Barthes used semiotic analysis to show how popular culture creates ideological meaning. However, in his later work, notably The Death of the Author (1967), Barthes abandoned the structuralist idea of fixed meaning in favor of post-structuralism’s emphasis on reader-centric interpretation.

In “The Death of the Author,” Barthes argues that the authority of the author in determining a text’s meaning must be eliminated. Instead, meaning emerges through the interaction between text and reader, with the text being a site of multiple meanings rather than a singular, fixed message. The reader, then, becomes the locus of meaning-making, while the author is rendered irrelevant.

This idea radically challenged literary criticism, historical analysis, and cultural studies. Barthes’s idea aligns closely with post-structuralism’s broader emphasis on the instability of meaning and the multiplicity of interpretations. His later work,

S/Z, deconstructs a Balzac short story using a system of “codes” that exposes the layered nature of meaning within any given text, a method that profoundly influenced narratology, media studies, and critical theory.

Jean-François Lyotard: Incredulity Toward Metanarratives

Lyotard’s The Postmodern Condition (1979) became a canonical text in post-structuralist discourse, especially in the context of postmodernism. He critiques the grand, totalizing narratives—or metanarratives—of Enlightenment reason, progress, and Marxist historical materialism. According to Lyotard, the contemporary world is characterized by skepticism toward these overarching ideologies, replaced instead by a plurality of small, localized narratives.

Lyotard argues that knowledge in the postmodern age is increasingly commodified and fragmented, resulting in a situation where different language games and discourses compete without any central authority. This rejection of universal truths aligns with the post-structuralist emphasis on the multiplicity of meaning and the situatedness of knowledge.

For Lyotard, truth is no longer a singular, objective reality but is produced within particular discourses. Science, art, politics, and ethics are governed by different rules and cannot be judged by a universal standard. His work not only offers a critique of modernist epistemology but also questions the legitimacy of institutional power, making it especially relevant to the sociology of knowledge, education systems, and cultural production.

Julia Kristeva: Intertextuality and the Semiotic

Julia Kristeva brought a feminist and psychoanalytic dimension to post-structuralism through her concepts of intertextuality, the semiotic, and abjection. Building on Bakhtin and Lacan, Kristeva argues that every text is an amalgamation of other

texts—echoing, quoting, and transforming them—thus undermining the idea of original authorship.

Her notion of intertextuality is not just about citation or influence; it emphasizes that texts are embedded in cultural and historical matrices that continuously generate and regenerate meaning. This idea reinforces the post-structuralist position that meaning is dynamic and contingent upon context, discourse, and interpretation.

Kristeva also introduced the concept of the semiotic, a pre-linguistic realm of bodily drives and rhythms that exists alongside the symbolic (structured, rule-based language). In this way, she challenged Lacan’s rigid symbolic order, offering a more fluid conception of identity and meaning that accommodates affect, desire, and the maternal body. Her concept of abjection, where the subject defines itself by rejecting what it deems impure or threatening, has been influential in feminist theory and cultural studies, especially in analyzing how societies create boundaries around race, gender, and morality.

Michel Serres and Gilles Deleuze: Multiplicity and Rhizomatic Thinking

Gilles Deleuze (often writing with Félix Guattari) revolutionized post-structuralist thought with an emphasis on multiplicity, deterritorialization, and rhizomatic knowledge structures. In A Thousand Plateaus (1980), Deleuze and Guattari contrast the hierarchical “arborescent” model of knowledge with the “rhizome”—a non-linear, non-hierarchical network where ideas and identities proliferate endlessly.

This conceptual shift reflects the post-structuralist commitment to decentralization and fluidity. For Deleuze, concepts like identity, knowledge, and society are not fixed or essential but constantly becoming—an idea deeply resonant with the post-structuralist critique of binary oppositions and rigid categories.

Deleuze’s notion of the “body without organs” further explores the idea of dismantling structured, regulated bodies (social, political, or personal) to allow for new forms of becoming and experimentation. His philosophy has found application

in art theory, queer studies, cybernetics, and even ecology, where rigid structures are replaced by relational, processual thinking.

Applications of Post-Structuralism in Contemporary Sociology and Culture

Post-structuralism has had far-reaching implications beyond philosophy and literary theory. In sociology, its ideas have reshaped understandings of power, identity, gender, class, and race. For instance:

- In gender studies, post-structuralism challenges essentialist notions of masculinity and femininity. Thinkers like Judith Butler (inspired by Foucault and Derrida) argue that gender is not a biological given but a performative act regulated by discursive norms.

- In education, the work of Lyotard and Foucault informs critiques of institutional knowledge, questioning whose knowledge is valued and how curricula reinforce dominant ideologies.

- In media and cultural studies, the concept of intertextuality, power/knowledge, and simulacra (from Baudrillard) are used to deconstruct mass media, advertisements, and pop culture texts.

- In postcolonial studies, thinkers like Homi Bhabha and Gayatri Spivak use post-structuralist tools to analyze how colonial discourse creates the “other” and sustains cultural hegemony through language, education, and representation.

Critiques of Post-Structuralism

Despite its wide influence, post-structuralism has faced substantial criticism. Critics argue that its extreme relativism and rejection of objectivity undermine the possibility of political action or social justice. If truth is always contingent and language is infinitely interpretable, how can we establish any foundation for rights, ethics, or solidarity?

Marxist critics like Terry Eagleton argue that post-structuralism depoliticizes theory by focusing excessively on language and discourse rather than material conditions. Others see it as elitist or overly obscure, relying on jargon and abstract concepts that distance it from real-world issues.

Even within feminist theory, while post-structuralism enabled the deconstruction of gender norms, some argue it fails to address the structural inequalities and lived experiences of women in tangible ways.

However, defenders of post-structuralism claim that these critiques miss the point: post-structuralism is not about denying truth but about interrogating how truths are produced, legitimized, and weaponized. It invites a more nuanced and democratic way of thinking that avoids totalitarian certainties.

Conclusion

Post-structuralism emerged as a powerful critique of modernity, Enlightenment rationality, and structuralist rigidity. It replaced fixed meanings with multiplicity, challenged the authority of authors and institutions, and revealed how power operates subtly through language, discourse, and knowledge production.

Through the contributions of thinkers like Foucault, Derrida, Barthes, Lyotard, Kristeva, Lacan, and Deleuze, post-structuralism continues to inform contemporary debates in sociology, politics, literature, education, gender, and media. Its emphasis on difference, contingency, and the deconstruction of totalities offers a vital intellectual toolkit for navigating today’s complex and plural world.

In an age of fake news, cultural polarization, and surveillance capitalism, the post-structuralist reminder—that what we take for granted as truth, order, and identity is often constructed through invisible mechanisms of power—remains more relevant than ever.

References

- Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish. New York: Vintage Books, 1977.

- Derrida, Jacques. Of Grammatology. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976.

- Barthes, Roland. Image, Music, Text. London: Fontana Press, 1977.

- Lyotard, Jean-François. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. University of Minnesota Press, 1984.

- Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Félix. A Thousand Plateaus. University of Minnesota Press, 1987.

- Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble. Routledge, 1990.

Michel Foucault (1926-84). Jacques Derrida (1976) and Julia Kristeva (1974) are the most influential figures in an intellectual movement known as post structuralism. However, it is the work of Foucault that influenced sociology and the social sciences. In his work, he illustrated shifts of understanding which separate thinking in the modern world from that of earlier ages. In his writings on crime, the body, madness and sexuality, Foucault analyzed the emergence of modern institutions such as prisons, hospitals and schools having played an increasing role in controlling and monitoring the social population. He wanted to show that there was 'another side' to Enlightenment ideas about individual liberty concerned with discipline and surveillance. Foucault advanced important ideas about the relationship between power, ideology and discourse in relation to modern organizational systems.

The study of power that relates to how individuals and groups achieve their end against those of others is of fundamental importance in sociology. Marx and Weber laid particular emphasis on power. Foucault continued some of the ideas they pioneered. The role of discourse is central to his thinking about power and control in society. He used the term to refer to ways of talking or thinking about particular subjects that are united by common assumptions. Foucault demonstrated the dramatic way in which discourses of madness changed from medieval times through to the present day. In the Middle Ages the insane were generally regarded as harmless; some believed that they might even have possessed a special 'gift' of perception. In modern societies, however, 'madness' has been shaped by a medicalized discourse, emphasizing illness and treatment. This medicalized discourse is supported and perpetuated by a highly developed and influential network of doctors, medical experts, hospitals, professional associations and medical journals.

Foucault states that power works through discourse to color popular attitudes towards phenomena such as crime, madness or sexuality. Expert discourses established by those with power or authority can often be countered only by competing expert discourses. In such a way, discourses can be used as a powerful tool to restrict alternative ways of thinking or speaking while knowledge becomes a force of control. Most of the Foucault's writings highlight the way power and knowledge are linked to technologies of surveillance, enforcement and discipline.

Foucault's radical new which characterized many of his early works, has become known as Foucault's archaeology' of knowledge. Foucault set about the task to make sense of the familiar by digging into the past. He energetically attacked the present the taken-far-granted concepts, beliefs and structures that are largely invisible precisely because they are familiar. For example, he explored how the notion of' sexuality has not always existed, but has been created through processes of social development. Foucault work on the assumptions behind current beliefs and practices to make the present 'visible' by accessing it from the past.

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|