Social Change

Index

Introduction to Social Change

Social change refers to the significant transformation over time in the

structure, function, and cultural practices of a society. These

transformations may be gradual or rapid, subtle or revolutionary, and can

affect the norms, values, institutions, and relationships that define a

community’s way of life. Change is intrinsic to human society—indeed, no

society remains static. Even in societies often perceived as “traditional” or

“primitive,” layers of subtle changes in beliefs, economic activity, kinship

patterns, or political structures have occurred over centuries. The

industrial and scientific revolutions of the 18th and 19th centuries

accelerated this pace of change, transforming not only the economic

structures of societies but also their political ideologies, family systems,

and modes of communication. Thus, sociologists have long been

interested in both the agents and consequences of such transformations,

making social change one of the foundational areas of study in sociology.

While continuity ensures the stability of society, change introduces the

dynamics of evolution and transformation. These twin forces coexist,

reinforcing the sociological idea that societies are complex systems

capable of adaptation and renewal. For instance, although the Indian joint

family system has undergone considerable changes, it continues to exist in

modified forms. The same applies to caste—while its rigid hierarchical

form is weakening, it finds new expressions in modern political and social

arrangements.

Understanding Social Change and Development

Social change and development are often used interchangeably but differ

in conceptual depth and normative implication. Social change is a neutral

term—it refers to any alteration in social structure or behavior, whether

positive or negative. Development, however, implies change in a desirable

direction, aimed at improving human welfare and enhancing quality of life.

Developmental change is usually goal-oriented, driven by planning, policy,

and ideology. For example, post-colonial nations like India initiated

structured developmental plans to address poverty, illiteracy, gender

inequality, and underdevelopment.

Yet, the notion of development is not without criticism. Not all

developmental changes are beneficial to all sections of society. A large

dam may be considered developmental by economists for its contributions

to energy and irrigation, but the displacement it causes can ruin the lives

of marginalized communities. Hence, sociologists and environmentalists

advocate for sustainable development, a concept popularized by the

Brundtland Report (1987), which emphasizes meeting present needs

without compromising the ability of future generations to meet theirs.

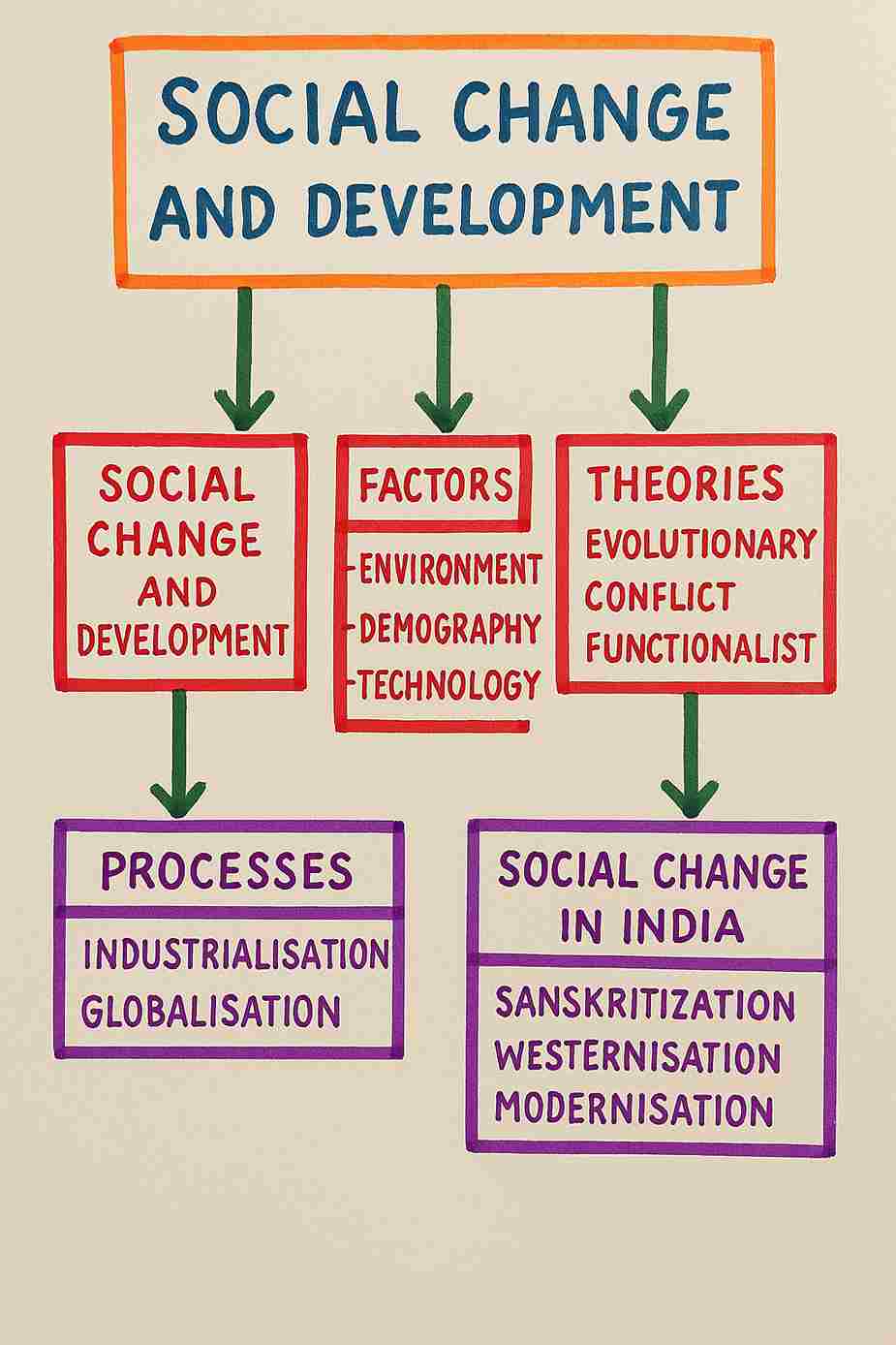

Factors Contributing to Social Change

A. Physical Environment

The environment shapes society in profound ways. Natural resources, climate, topography, and disasters such as floods or earthquakes influence social organization and cultural responses. For instance, the drying up of rivers or deforestation has historically contributed to the decline of civilizations such as Mesopotamia and the Harappan Valley. Today, climate change, rising sea levels, and natural disasters continue to force communities to migrate, adapt, or restructure their lives and institutions, thus triggering social change.

B. Demographic Factors

Population dynamics—birth rate, death rate, age structure, and migration—play a crucial role in shaping social life. Rapid population growth can strain infrastructure, healthcare, and education, pushing the state to restructure policies. Aging populations in developed countries like Japan demand changes in labor markets and social security systems, while the youth bulge in countries like India presents both an opportunity for growth and a challenge in terms of employment and resource distribution.

C. Technological Factors

Technology is perhaps the most dynamic force behind social change. From the printing press to the internet, every major technological innovation has disrupted and restructured social relationships and institutional frameworks. The “Information Revolution” driven by the internet and mobile technologies has transformed how people work, learn, communicate, and consume. Karl Marx emphasized the role of productive forces (technology and labor) in shaping society—arguing that changes in material conditions lead to transformations in social relations.

D. Cultural Factors

Ideas, beliefs, ideologies, and values are potent catalysts of change. Max Weber’s study The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism demonstrated how religious values encouraged rational economic behavior in Western Europe. Conversely, in India, religious values and caste ideology were seen as impediments to capitalism and modern industrialism. Cultural shifts in values—like greater acceptance of gender equality or increased emphasis on education—can fundamentally transform family, religion, politics, and work.

Theories of Social Change

4.1 Evolutionary Theories

These theories see social change as a progressive and linear process.

Auguste Comte, the father of sociology, proposed the Law of Three Stages:

theological, metaphysical, and positive (scientific). Herbert Spencer

adapted Darwin’s evolutionary theory to society, coining the term “survival

of the fittest.” He believed societies evolve from simple to complex. Lewis

Henry Morgan saw social evolution through technological development,

categorizing societies into stages of savagery, barbarism, and civilization.

Although influential, these theories have been criticized for ethnocentrism

and unilinear determinism. They often considered Western societies as

the apex of development, neglecting diverse cultural paths and

overlooking the complexity of social change in non-Western contexts.

4.2 Conflict Theory

Karl Marx provided a materialist interpretation of history. He argued that social change arises from conflicts rooted in economic inequalities—primarily the class struggle between the proletariat (workers) and bourgeoisie (owners). According to Marx, each mode of production carries the seeds of its own destruction. For example, capitalism, through its inherent exploitation and contradictions, would eventually give way to socialism and, eventually, communism. This radical and transformative view of social change has influenced revolutionary movements and critical sociology across the globe.

4.3 Structural Functionalism

Structural-functionalists like Emile Durkheim and Talcott Parsons viewed society as an organism striving for balance. For them, change occurs when parts of society become dysfunctional and require readjustment. Durkheim introduced the idea of anomie to describe normlessness arising from rapid change, especially during industrialization. He also distinguished between mechanical solidarity (based on similarity in pre-modern societies) and organic solidarity (based on interdependence in complex societies). Parsons saw society as a system of interrelated parts in equilibrium. When one part changes (e.g., economic organization), others (e.g., family or education) must adapt to restore balance. However, functionalism has been critiqued for ignoring power, inequality, and conflict.

4.4 Other Theoretical Approaches

Ferdinand Tönnies’ distinction between Gemeinschaft (community) and Gesellschaft (society) captured the shift from intimate, kinship-based ties to impersonal, contractual relationships in modern societies. Oswald Spengler’s cyclical theory viewed civilizations as going through birth, growth, decline, and death. Vilfredo Pareto proposed the “circulation of elites” to explain how new groups replace old elites in cycles of change. Modernisation theorists in the mid-20th century emphasized adopting Western-style development in the global South. However, this was critiqued by Dependency Theorists and World-Systems Theorists like Immanuel Wallerstein, who argued that global capitalism keeps poor nations dependent and underdeveloped. These perspectives highlight the global context and power relations in shaping social change.

Processes of Social Change

5.1 Industrialisation and Modernisation

Industrialization transformed the economic base of society—shifting labor from agriculture to factories, creating urban centers, and fostering mass production. The Industrial Revolution, which began in 18th-century Britain, changed population patterns, work structures, gender roles, and family systems. Industrialization is not merely economic; it reconfigures the entire cultural and political structure.

Modernization, a broader term, includes economic, social, and psychological changes that accompany industrial growth. It involves secularism, rationality, mobility, and individualism. However, modernization is not uniform. In India, it has taken hybrid forms—traditional institutions often coexisting with modern democratic ones. The state-led industrialization in India post-1947 was seen as a pathway to development, but it also produced regional and class inequalities.

5.2 Industrialisation and Urbanisation

Urbanization is closely linked to industrialization. As factories concentrated in cities, rural populations migrated in search of work. Cities became hubs of economic activity but also of inequality, congestion, and environmental degradation. The rise of mega-cities has created slums, informal employment, and severe ecological stress. Urban life changes social relations. Tönnies and Durkheim described how modern urban societies replace emotional, collective relationships with impersonal, contractual ones. While cities can offer anonymity and freedom, they also bring loneliness and alienation. In India, urbanization offers avenues for caste and gender mobility, as traditional controls weaken, but also introduces new forms of stratification.

5.3 Secularisation

Secularisation refers to the diminishing influence of religion in societal affairs. Modern societies increasingly rely on rationality, science, and legal frameworks over religious explanations. In pre-modern societies, illness or misfortune may have been attributed to divine wrath or supernatural causes. In modern contexts, these are seen through medical and scientific lenses. However, secularisation does not necessarily mean the decline of religiosity; it implies a reconfiguration where religion becomes a personal rather than institutional affair.

5.4 Globalisation

Globalisation is the process by which the world becomes interconnected

economically, culturally, and politically. Anthony Giddens defines it as the

“intensification of worldwide social relations.” Yogendra Singh notes five

aspects: technological revolution in communication, global capital

circulation, cultural homogenization, expansion of electronic media, and

transnational migration.

Globalisation has created a global market dominated by multinational

corporations. It brings consumerism, cultural imperialism (e.g.,

Americanization), and marginalization of local economies. Yet, it also

offers opportunities for cultural hybridization and diasporic communities

to maintain transnational identities. In India, globalization has

transformed consumption patterns and created a new middle class, but

has also widened inequality

Social Change in India: An Overview

India’s experience of social change is deeply shaped by its colonial past, civilizational legacy, and post-independence democratic experiment. Processes such as Sanskritization, Westernisation, and Modernisation illustrate different pathways through which Indian society has responded to change.

6.1 Sanskritization

Coined by M. N. Srinivas, Sanskritization refers to the process by which lower castes adopt the practices and rituals of higher castes to improve their social status. While it allows limited upward mobility, it reinforces caste hierarchy and legitimizes inequality. It fails to challenge the system structurally and often leads to imitation of regressive practices such as dowry or female seclusion.

6.2 Westernisation

Westernisation denotes changes due to British colonialism and exposure to Western institutions, education, and values. Social reformers like Raja Ram Mohan Roy adopted Western liberal ideas to combat social evils. However, Westernisation is mostly visible among urban middle classes and often manifests in lifestyles rather than democratic or egalitarian values.

6.3 Modernisation

Yogendra Singh explored how Indian traditions have adapted to modern influences without disappearing. He coined the term “neo-traditionalism” to describe the survival of traditional forms within modern structures. He also spoke of the crisis of success (growth without inclusion) and crisis of failure (persistent poverty and inequality). Singh’s work emphasizes that social change in India is multi-layered—economic change coexists with casteism, communalism, and regionalism

Conclusion

Social change is a complex, multi-dimensional, and often contested process. It can be driven by structural forces like economy, demography, and technology, or by cultural shifts, ideologies, and political movements. Development is a specific type of social change aimed at improving human well-being, but its meaning is often contested depending on who defines progress. Theories of social change—from evolution to conflict—help us understand its direction, agents, and consequences.

India’s experience reflects the coexistence of tradition and modernity, continuity and transformation. Understanding social change through the lenses of globalisation, industrialisation, secularisation, and cultural shifts allows us to appreciate the dynamism and resilience of societies. To ensure just and inclusive development, sociologists urge us to critically assess the processes and structures shaping our present and future.

References

- Giddens, Anthony (1990). The Consequences of Modernity. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Ritzer, George (1993). The McDonaldization of Society. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press.

- Srinivas, M. N. (1966). Social Change in Modern India. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Singh, Yogendra (1973). Modernization of Indian Tradition. New Delhi: Thomson Press

The term social change is used to indicate the changes that take place in human interactions and interrelations. Society is a web of social relationships and hence social change means change in the system of social relationships. These are understood in terms of social processes and social interactions and social organization.

Auguste Comte the father of Sociology has posed two problems- the question of social statics and the question of social dynamics, what is and how it changes. The sociologists not only outline the structure of the society but also seek to know its causes also.

According to Morris Ginsberg social change is a change in the social structure.

|

|

- Evolutionary Theories

- Factors of Change

- Impact of Technological Change

- Social Movements Types

- Books and Author

- Points to Remember

Read about How Social Media Affects Family Relationships on AcademicHelp.net

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|