Home » Social Thinkers » Margaret Mead

Margaret Mead

Index

Introduction

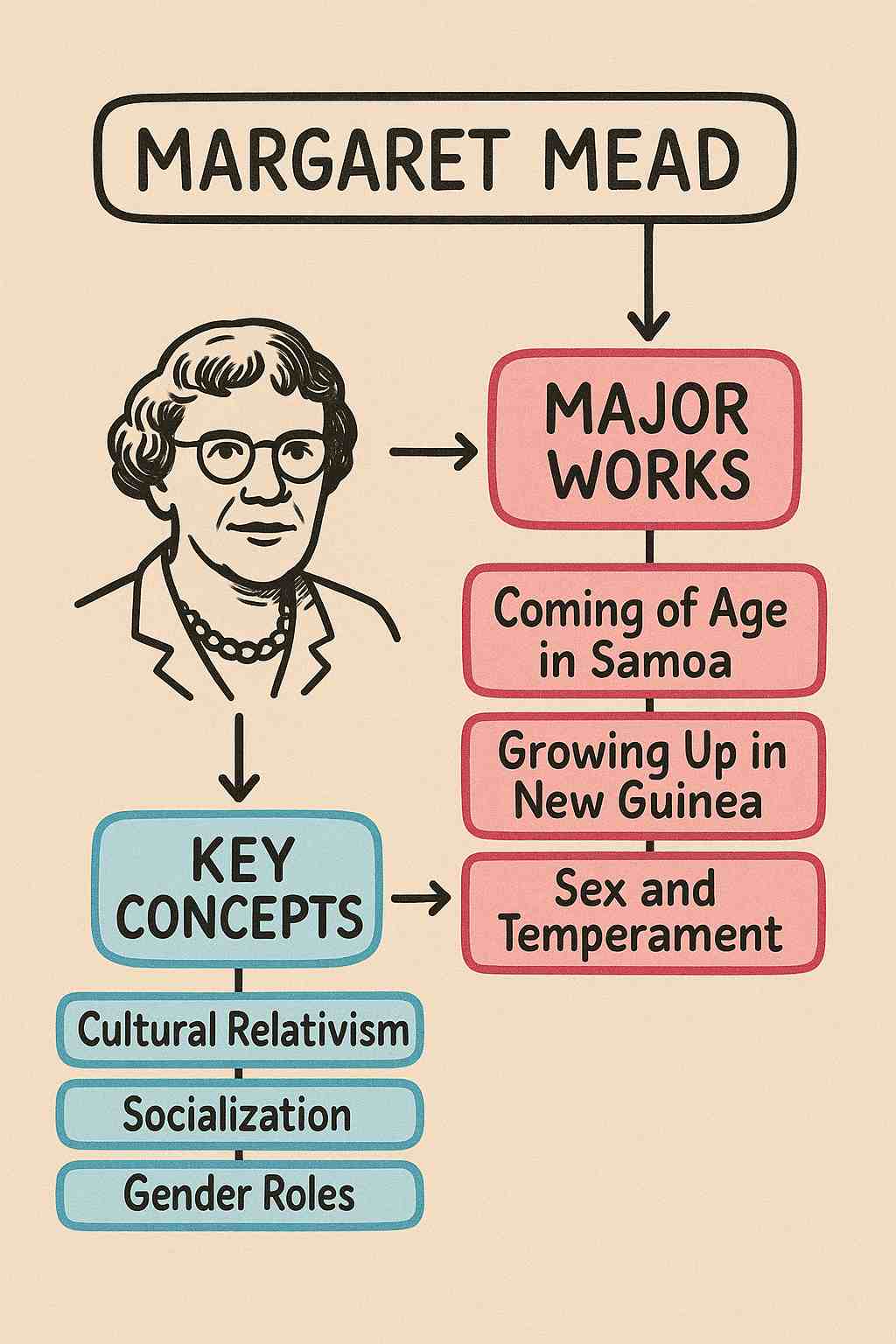

Margaret Mead (1901–1978) stands as a towering figure in 20th-century anthropology, renowned for her pioneering fieldwork, accessible writing, and profound influence on how societies perceive culture, gender, and human development. Born on December 16, 1901, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Mead broke barriers as a woman in academia, becoming a public intellectual whose work transcended scholarly circles to shape broader cultural conversations. Her immersive studies in the South Pacific—particularly in Samoa, New Guinea, and Bali—revealed the extraordinary diversity of human societies, challenging Western assumptions about universal norms. Mead’s ability to translate complex anthropological insights into relatable narratives made her a household name, with books like Coming of Age in Samoa (1928) sparking widespread interest in cultural anthropology. Over her career, she authored or co-authored over 30 books and thousands of articles, lectures, and public appearances, cementing her role as a bridge between academia and the public. As a feminist, educator, and advocate for cross-cultural understanding, Mead’s legacy continues to inspire discussions on cultural relativism, gender roles, and the malleability of human behavior, though her work has not been without controversy.

Intellectual Background

Mead’s intellectual development was shaped by a unique blend of progressive education, interdisciplinary influences, and mentorship from leading anthropologists. Raised in a family that prioritized intellectual curiosity—her father, Edward Mead, was a professor of economics, and her mother, Emily Fogg Mead, a sociologist—Mead was encouraged to explore diverse fields from an early age. Homeschooled initially and exposed to Quaker values of inquiry and equality, she developed a keen interest in human behavior. At DePauw University, she briefly studied before transferring to Barnard College, where she earned her bachelor’s degree in 1923. At Barnard, sociologist William Fielding Ogburn introduced her to cultural determinism, the idea that social structures shape individual behavior, which became a cornerstone of her thinking. Pursuing graduate studies at Columbia University under Franz Boas, the “father of American anthropology,” and his student Ruth Benedict, Mead embraced cultural relativism, rejecting the racial and biological determinism prevalent in early 20th-century scholarship. Boas’s emphasis on rigorous fieldwork inspired Mead’s immersive approach, while Benedict’s focus on culture and personality influenced her explorations of individual-society dynamics. Mead also engaged with psychoanalytic theories, particularly Freud’s, adapting them to study how culture molds psychological development. Her exposure to psychology, sociology, and anthropology, combined with her feminist sensibilities, equipped her to challenge conventional wisdom and conduct groundbreaking cross-cultural research.

Key Ideas and Concepts

Mead’s contributions to anthropology are anchored in several enduring concepts that reshaped the discipline and broader social thought. Central to her work was cultural relativism, the principle that behaviors, values, and norms must be understood within their cultural context rather than judged against universal or Western standards. This idea, rooted in Boasian anthropology, challenged ethnocentrism and fostered empathy for diverse societies. Mead’s research on gender roles was revolutionary, particularly her finding that traits deemed “masculine” or “feminine” in Western societies were not biologically determined but culturally constructed. In Sex and Temperament in Three Primitive Societies (1935), she demonstrated how gender expectations varied across cultures, laying a foundation for feminist anthropology and later gender studies. Her work on adolescence, notably in Coming of Age in Samoa (1928), argued that the turmoil associated with youth in Western societies was not a universal biological phase but a product of cultural norms, particularly around sexuality and social expectations. Mead’s culture and personality framework explored how societal structures shape individual behavior and vice versa, integrating anthropological and psychological insights. Her methodological innovation, participant observation, involved living among the communities she studied, allowing her to capture nuanced, empathetic portrayals of their lives. Additionally, Mead’s interest in child-rearing practices highlighted how early socialization influences personality and cultural continuity, a theme central to her work in New Guinea and beyond. These ideas collectively underscored her belief in the plasticity of human behavior and the power of culture to shape diverse ways of life.

Major Works and Their Explanations

- Coming of Age in Samoa (1928): Based on nine months of fieldwork in Samoa at age 23, this book catapulted Mead to fame. Studying adolescent girls in the village of Ta‘ū, Mead argued that Samoan youth experienced less emotional and psychological turmoil than American teens due to relaxed cultural attitudes toward sexuality, family, and social roles. The book challenged Western assumptions about adolescence as a universally turbulent stage, suggesting that cultural environments shape developmental experiences. Its accessible prose and provocative findings made it a bestseller, introducing anthropology to a wide audience, though it later faced scrutiny for its conclusions.

- Growing Up in New Guinea (1930): Following her Samoan research, Mead studied the Manus people of the Admiralty Islands. This book focused on child-rearing practices and their impact on personality development. Mead observed that Manus children were raised with strict discipline, contrasting with Samoan permissiveness, and argued that these practices shaped distinct cultural traits like pragmatism and economic focus. The work emphasized the role of early socialization in cultural continuity, offering insights into how societies reproduce their values through upbringing.

- Sex and Temperament in Three Primitive Societies (1935): Based on fieldwork in New Guinea, this book examined gender roles among the Arapesh, Mundugumor, and Tchambuli. Mead found that the Arapesh valued nurturing in both genders, the Mundugumor prized aggression in both, and the Tchambuli reversed Western gender norms, with women as dominant and men as expressive. These findings challenged the idea of fixed gender roles, arguing that culture, not biology, determines gendered behavior. This work became a cornerstone for feminist anthropology and debates on gender fluidity.

Critics

Mead’s work, while transformative, has faced significant criticism, sparking debates that highlight the complexities of anthropological research. The most prominent critique came from Derek Freeman in his 1983 book Margaret Mead and Samoa: The Making and Unmaking of an Anthropological Myth. Freeman argued that Mead’s portrayal of Samoan culture as sexually permissive and free of adolescent turmoil in Coming of Age in Samoa was inaccurate, claiming her young informants may have misled her due to her inexperience and cultural relativist bias. He suggested that Samoan society was more restrictive and hierarchical, accusing Mead of romanticizing her findings to fit Boasian ideals. This critique ignited a fierce debate, with some anthropologists defending Mead’s work as contextually valid for its time, while others saw Freeman’s attack as exaggerated and rooted in his own biases. Critics also argued that Mead’s generalizations about entire cultures sometimes oversimplified complex social realities, reflecting the limitations of early anthropology’s interpretive methods. Her reliance on psychoanalytic frameworks, popular in the 1920s and 1930s, drew skepticism as those theories waned in influence. Feminist scholars later critiqued Mead for not fully addressing power dynamics in gender roles, though many credit her with laying the groundwork for feminist anthropology. The Freeman-Mead debate remains a touchstone in anthropology, raising questions about fieldwork reliability, cultural bias, and the ethics of representation. Despite these controversies, Mead’s defenders emphasize her pioneering role in challenging ethnocentrism and her methodological innovations, which continue to shape the discipline.

Contemporary Relevance

Margaret Mead’s ideas remain strikingly relevant in the 21st century, offering insights into pressing global issues. Her advocacy for cultural relativism informs efforts to foster cross-cultural understanding in an increasingly interconnected world, where globalization and migration highlight the need for empathy and respect for diverse perspectives. This principle is evident in fields like international development, education, and diplomacy, where Mead’s work encourages policies that honor cultural context. Her findings on gender roles resonate in contemporary debates on gender identity, non-binary frameworks, and equality, influencing feminist theory, queer studies, and activism. By demonstrating that gender is culturally constructed, Mead’s work supports arguments for dismantling rigid norms and promoting inclusivity. Her insights into adolescence remain pertinent in discussions of youth mental health, where cultural expectations shape experiences of stress and identity formation. Mead’s participant observation methodology continues to guide anthropologists, emphasizing ethical, immersive research that prioritizes community voices. Her interdisciplinary approach—blending anthropology, psychology, and sociology—inspires modern scholars to tackle complex issues like climate change, technology, and social justice through collaborative lenses. Mead’s public engagement, through lectures, media, and writing, serves as a model for academics seeking to bridge scholarship and society, as seen in efforts to communicate science during crises like pandemics or environmental challenges. However, the controversies surrounding her work remind researchers to approach cross-cultural studies with rigor, transparency, and awareness of their own biases. Mead’s legacy endures as a call to celebrate human diversity while critically examining the cultural forces that shape our lives.

References

- Mead, M. (1928). Coming of Age in Samoa. William Morrow & Company.

- Mead, M. (1930). Growing Up in New Guinea. William Morrow & Company.

- Mead, M. (1935). Sex and Temperament in Three Primitive Societies. William Morrow & Company.

|

|

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|