Home >> Environment and Sociology

Environment and Sociology

Index

Introduction

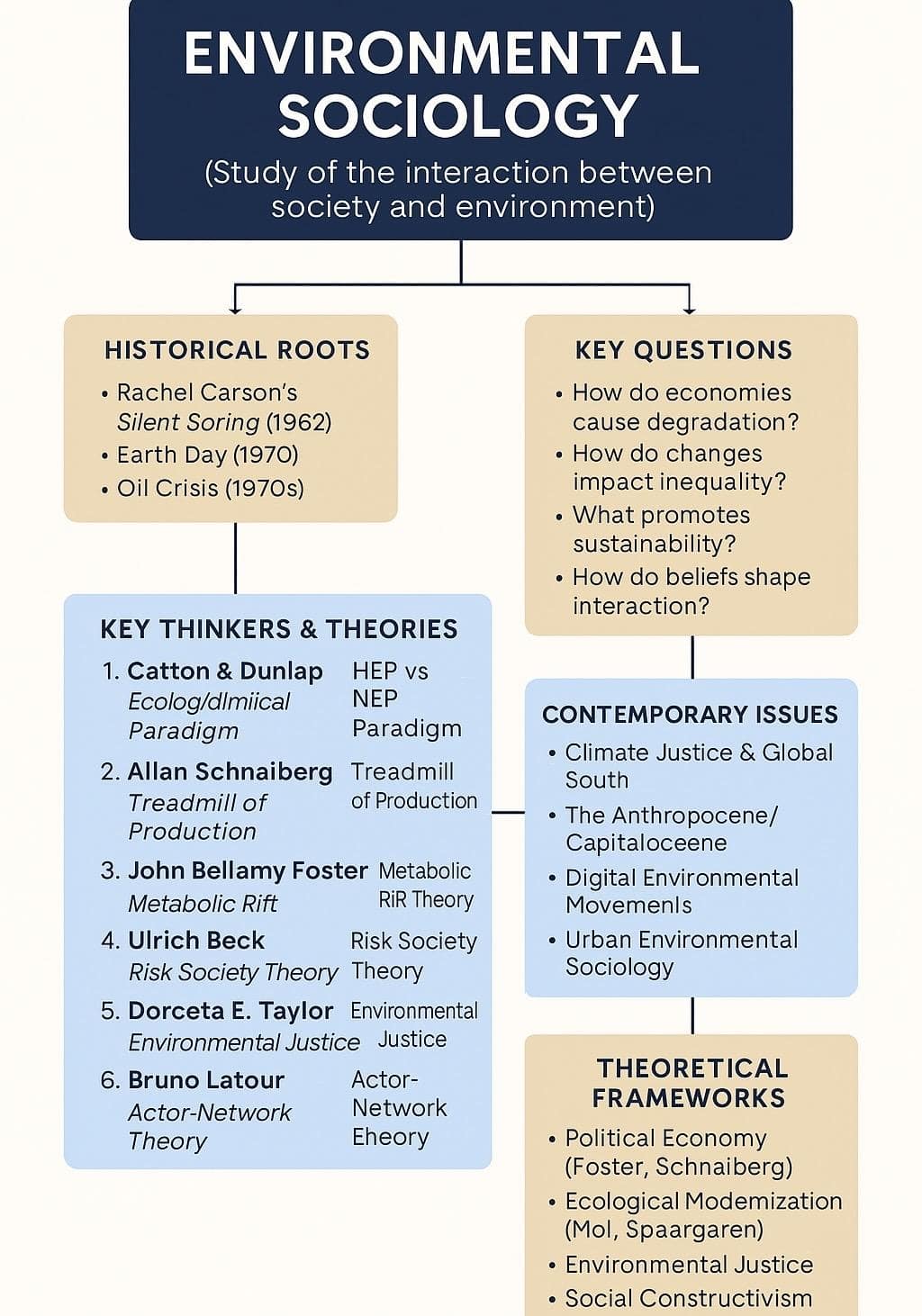

Environmental sociology represents one of the most dynamic and critically important subfields within contemporary sociological inquiry. Through extensive research and analysis, this comprehensive exploration examines the intricate relationships between human societies and their natural environments. This field transcends traditional disciplinary boundaries by investigating how social structures, cultural practices, and power dynamics fundamentally shape environmental conditions, while simultaneously analyzing how environmental transformations influence social organization, inequalities, and collective behaviors.

The urgency of environmental crises in the 21st century has positioned environmental sociology at the forefront of academic discourse. This research demonstrates how this field offers essential insights into pressing global challenges including climate change, resource depletion, biodiversity loss, and environmental justice. By integrating sociological theory with ecological realities, environmental sociology provides a robust analytical framework for understanding and addressing the complex socio-environmental challenges of our time.

Historical Development and Theoretical Foundations

The Emergence of Environmental Sociology

This analysis traces the origins of environmental sociology to the transformative period of the 1960s and 1970s, when environmental crises and social movements converged to challenge conventional sociological thinking. The publication of Rachel Carson’s groundbreaking work *Silent Spring* (1962), which exposed the devastating environmental and health impacts of pesticide use, served as a catalyst for environmental awareness. The first Earth Day in 1970 mobilized millions of Americans around environmental concerns, while the oil crises of the 1970s highlighted the vulnerabilities of resource-dependent societies.

These pivotal events prompted sociologists to critically examine what William R. Catton Jr. and Riley E. Dunlap identified as the “human exemptionalism paradigm” (HEP). This dominant worldview assumed that human societies could transcend ecological limits through technological innovation and economic growth. Environmental sociology emerged as a direct challenge to this paradigm, emphasizing instead the fundamental interdependence of social and ecological systems.

Through this research, several core questions that define environmental sociology have been identified:

- How do economic systems and production processes contribute to environmental degradation?

- In what ways do environmental changes exacerbate existing social inequalities?

- What social processes and institutional arrangements can promote ecological sustainability?

- How do cultural values and belief systems shape human-environment interactions?

Major Theoretical Contributions and Intellectual Debates

William R. Catton Jr. and Riley E. Dunlap: Ecological Limits and Environmental Paradigms

This analysis of Catton and Dunlap’s contributions reveals their fundamental

role in establishing environmental sociology as a distinct field. Catton’s

concept of “ecological overshoot,” detailed in his seminal work *Overshoot:

The Ecological Basis of Revolutionary Change* (1980), argues that

industrialized societies systematically exceed Earth’s carrying capacity

through unsustainable consumption patterns. His analysis of resource

depletion, particularly fossil fuels and arable land, provides a sobering

assessment of civilization’s ecological trajectory.

Dunlap’s development of the New Environmental Paradigm (NEP), initially

conceptualized with Kent Van Liere in 1978, represents a paradigmatic shi in

environmental thinking. The NEP posits that humans are integral components

of nature, subject to ecological constraints and interdependent with other

species. The NEP scale, widely employed in empirical research, measures

environmental attitudes across diverse populations and cultural contexts.

However, critical analysis identifies several limitations in their approach.

Critics argue that Catton’s emphasis on ecological limits risks environmental

determinism, potentially underestimating human agency and adaptive

capacity. The NEP scale has been criticized for its Western-centric

assumptions, which may inadequately capture non-Western or Indigenous

environmental worldviews that emphasize relational rather than

resource-based connections to nature.

Allan Schnaiberg: The Treadmill of Production Theory

Schnaiberg’s “treadmill of production” theory, elaborated in *The

Environment: From Surplus to Scarcity* (1980), provides a sophisticated

analysis of capitalism’s inherent anti-ecological tendencies. This research

demonstrates how this theory illuminates the structural contradictions

between economic growth imperatives and environmental sustainability. The

treadmill creates a self-reinforcing cycle where competitive pressures drive

continuous expansion of production, resource extraction, and waste

generation.

Schnaiberg’s analysis reveals how this process concentrates benefits among

economic elites while externalizing environmental costs onto marginalized

communities. This insight laid crucial groundwork for environmental justice

scholarship, highlighting the unequal distribution of environmental risks and

benefits across social groups.

The treadmill theory has generated significant theoretical debate within

environmental sociology. Ecological modernization theorists, including

Arthur Mol and Gert Spaargaren, challenge Schnaiberg’s pessimistic

assessment, arguing that technological innovation and environmental policy

reforms can achieve “decoupling” of economic growth from environmental

impact. Conversely, eco-Marxist scholars like John Bellamy Foster largely

align with Schnaiberg’s structural critique, emphasizing capitalism’s systemic

barriers to sustainability.

John Bellamy Foster: Eco-Marxism and Metabolic Ri Theory

Foster’s eco-Marxist analysis, particularly developed in *Marx’s Ecology:

Materialism and Nature* (2000) and *The Ecological Ri* (2010), provides a

sophisticated reinterpretation of Marx’s insights into capitalism’s ecological

contradictions. This analysis shows how Foster’s concept of “metabolic ri”

explains how capitalist production disrupts natural cycles and ecological

processes.

Foster’s historical analysis demonstrates how industrial agriculture, through

its extraction of soil nutrients without adequate replacement, creates a “ri”

in natural metabolic processes. This concept extends beyond agriculture to

encompass broader ecological crises including climate change, biodiversity

loss, and pollution. Foster’s critique of market-based environmental solutions,

such as carbon trading and payment for ecosystem services, argues that these

mechanisms fail to address capitalism’s fundamental anti-ecological logic.

Critics of Foster’s approach argue that his focus on capitalism potentially

overlooks other significant drivers of environmental degradation, including

state socialism’s environmental record, cultural factors, and demographic

pressures. Some ecological modernization scholars contend that Foster’s

rejection of technological solutions is overly pessimistic, while others praise

his structural analysis for identifying root causes of ecological crises.

Ulrich Beck: Risk Society and Reflexive Modernization

Beck’s risk society framework, developed in *Risk Society: Towards a New

Modernity* (1992), offers a comprehensive analysis of how modern societies

produce and manage human-made environmental risks. This research

demonstrates how Beck’s concept of “manufactured risks” - including climate

change, nuclear accidents, and chemical pollution - transcends traditional

social boundaries and affects all social classes, albeit unequally.

Beck’s theory of “reflexive modernization” suggests that societies must

critically assess and adapt to the unintended consequences of

industrialization. This process involves questioning fundamental assumptions

about progress, technology, and social organization. Beck’s analysis of how

risks are socially constructed, scientifically assessed, and politically managed

provides valuable insights into contemporary environmental governance.

However, critical analysis identifies several limitations in Beck’s approach.

Critics argue that his emphasis on global risks potentially overlooks localized

environmental problems, particularly in the Global South where traditional

risks remain significant. Others note that his framework underestimates the

role of power dynamics in risk distribution, as marginalized groups

consistently bear disproportionate environmental burdens.

Dorceta E. Taylor: Environmental Justice and Intersectional Analysis

Taylor’s groundbreaking work in environmental justice, exemplified in *The

Environment and the People in American Cities, 1600s–1900s* (2009) and

*Toxic Communities: Environmental Racism, Industrial Pollution, and

Residential Mobility* (2014), provides comprehensive documentation of how

environmental harms disproportionately affect marginalized communities.

Her research reveals how systemic racism, discriminatory zoning policies, and

economic inequalities result in communities of color bearing disproportionate

environmental burdens.

Taylor’s historical analysis traces the roots of environmental racism to colonial

periods and slavery, demonstrating how contemporary environmental

inequalities reflect centuries of discriminatory practices. Her work on

grassroots environmental movements highlights how affected communities

organize to challenge environmental injustices and advocate for equitable

policies.

Some scholars argue that Taylor’s focus on race and class could be expanded

to include more explicit attention to gender and intersectional perspectives.

Others praise her historical approach for revealing the deep structural roots of

environmental racism and her emphasis on community agency in

environmental advocacy.

Bruno Latour: Science, Technology, and Actor-Network Theory

Latour’s contributions to environmental sociology, particularly through *We

Have Never Been Modern* (1993) and *Facing Gaia: Eight Lectures on the New

Climatic Regime* (2017), bring science and technology studies perspectives to

environmental analysis. His critique of the modern nature-society dichotomy

proposes that humans and non-human entities exist in interconnected

actor-networks where agency is distributed across multiple actors.

Latour’s concept of the “new climatic regime” reframes climate change as a

fundamental transformation of human-Earth relationships requiring new

forms of global governance. His engagement with James Lovelock’s Gaia

hypothesis suggests that Earth systems actively respond to human activities,

challenging anthropocentric assumptions about environmental control.

Critics argue that Latour’s actor-network theory can be overly abstract,

making it challenging to apply to concrete policy solutions. Others value his

emphasis on non-human agency, which challenges anthropocentric

assumptions and opens new possibilities for understanding environmental

politics.

Theoretical Frameworks and Contemporary Debates

Environmental sociology employs several theoretical frameworks, each offering distinct perspectives on human-environment interactions:

Political Economy Approaches examine how economic systems, particularly capitalism, drive environmental degradation. This framework, rooted in Schnaiberg and Foster’s work, emphasizes structural contradictions between economic growth and environmental sustainability. Debates center on whether systemic transformation or reformist solutions are more effective.

Ecological Modernization Theory argues that technological innovation and policy reforms can achieve environmental sustainability within existing institutional frameworks. Scholars like Mol and Spaargaren contend that environmental protection can be compatible with economic growth through technological advancement and policy innovation.

Environmental Justice Frameworks highlight how environmental harms disproportionately affect marginalized communities. This approach emphasizes intersectionality, examining how race, class, gender, and indigeneity interact to shape environmental inequalities.

Social Constructivism examines how environmental problems are socially constructed through scientific, cultural, and political discourses. This approach, influenced by Latour’s work, explores how different actors define and respond to environmental issues.

Risk Society Theory emphasizes how modern societies produce and manage human-made environmental risks. Beck’s framework analyzes how risks are distributed across social groups and how societies adapt to uncertainty.

Methodological Approaches and Research Methods

Environmental sociology employs diverse methodological approaches to study human-environment interactions:

Quantitative Methods include surveys measuring environmental attitudes, such as the NEP scale, and statistical analyses examining relationships between social factors and environmental behaviors. Large-scale datasets enable researchers to identify patterns in environmental attitudes and behaviors across populations.

Qualitative Methods include ethnographic studies of environmental communities, in-depth interviews with environmental activists, and case studies of environmental conflicts. These methods reveal the lived experiences of environmental problems and the meanings people attach to environmental issues.

Mixed Methods Research combines quantitative and qualitative approaches to analyze both large-scale trends and local experiences. This approach enables researchers to understand both structural patterns and individual agency in environmental issues.

Historical Analysis traces the development of environmental problems and social responses over time. Scholars like Taylor use archival research to uncover the historical roots of environmental inequalities.

Network Analysis maps relationships between human and non-human actors in environmental systems. This method, inspired by Latour’s work, reveals how environmental governance involves complex networks of actors with different interests and capabilities.

Contemporary Issues and Emerging Challenges

Climate Justice and Global Inequalities

Climate change represents one of the most pressing challenges for environmental sociology. The field’s analysis reveals how climate impacts disproportionately affect the Global South, despite these regions contributing least to greenhouse gas emissions. Environmental sociologists examine how climate change exacerbates existing social inequalities and creates new forms of environmental injustice.

The Anthropocene and Planetary Boundaries

The concept of the Anthropocene, proposing that human activities have fundamentally altered Earth systems, has become central to environmental sociology. Scholars examine how this concept reshapes understanding of human-nature relationships and raises questions about planetary governance. Jason Moore’s critique of the Anthropocene, proposing the “Capitalocene” instead, emphasizes capitalism’s role in ecological transformation.

Digital Environmental Activism

Digital technologies are transforming environmental activism, creating new opportunities for mobilization and communication. Movements like #FridaysForFuture demonstrate how social media platforms can amplify environmental messages and coordinate global action. Environmental sociologists study how digital tools affect environmental movements while examining challenges like misinformation and digital divides.

Urban Environmental Sociology

Urbanization presents unique environmental challenges as cities concentrate population and economic activity. Environmental sociologists examine urban environmental problems including air pollution, waste management, and green space access. Research on environmental gentrification explores how environmental improvements can displace low-income communities.

Food Systems and Environmental Justice

Food production and consumption represent significant environmental challenges involving land use, water resources, and climate change. Environmental sociologists examine how industrial agriculture contributes to environmental degradation while exploring alternative food systems that promote sustainability and social justice

Conclusion

Environmental sociology provides essential insights for understanding the

complex relationships between human societies and their natural

environments. Through the foundational contributions of scholars like Catton,

Dunlap, Schnaiberg, Foster, Beck, Taylor, and Latour, the field has developed

sophisticated theoretical frameworks for analyzing ecological crises, social

inequalities, and human-environment interactions.

The field’s methodological diversity and interdisciplinary connections

enhance its capacity to address multi-scalar environmental challenges.

Contemporary issues including climate justice, the Anthropocene, digital

activism, and urban environmental problems demonstrate the field’s

continued relevance to 21st-century challenges.

As environmental crises intensify and social inequalities persist,

environmental sociology offers crucial tools for understanding and addressing

these interconnected challenges. The field’s emphasis on social justice,

structural analysis, and interdisciplinary collaboration positions it to

contribute significantly to creating more sustainable and equitable futures.

The ongoing development of environmental sociology reflects the urgent need

for social science perspectives on environmental issues. By continuing to

integrate sociological insights with ecological realities, the field provides

essential knowledge for navigating the complex environmental challenges of

the contemporary world.

References

- Beck, U. (1992). Risk society: Towards a new modernity (M. Ritter, Trans.). Sage Publications. (Original work published 1986)

- Carson, R. (1962). Silent spring. Houghton Mifflin

- Dunlap, R. E., & Van Liere, K. D. (1978). The “new environmental paradigm”: A proposed measuring instrument and preliminary results.

- Schnaiberg, A. (1980). The environment: From surplus to scarcity. Oxford University Press.

- Taylor, D. E. (2014). Toxic communities: Environmental racism, industrial pollution, and residential mobility. New York University Press.

Sociology can help us to understand how environmental problems are distributed in regions, countries and communities. For example although global warming will affect everyone on the planet, it will do so in different ways to different groups and communities.

Flooding kills many more people in low-lying, poor countries, such as Bangladesh, where housing and emergency infrastructures are less able to cope with severe weather than in Europe. In richer countries, such as the USA, the issues raised by global warming for policy- makers are likely to concern indirect effects, such as rising levels of immigration as people try to enter the country from areas more directly affected.

Sociologists can provide an account of how patterns of human behavior create pressure on the natural environment. The levels of pollution produced by industrialized countries would cause catastrophe if repeated in the world's poorer, non-industrial nations. Sociological theories of capitalist expansion, globalization or rationalization can help us to understand how human societies are transforming the environment.

policies and proposals aimed at providing solutions to environmental problems. For example, some environmental activists argue that people in the rich countries must turn away from consumerism and return to simpler ways of life living close to the land if global ecological disaster is to be avoided. They argue that rescuing the global environment will thus mean radical social as well as technological change.

However, given the enormous global inequalities that currently exist, there is little chance that the poor countries of the developing world will sacrifice their own economic growth because of environmental problems created largely by the rich countries. For instance, some governments in developing countries have argued that in relation to global warming there is no parallel between the 'luxury emissions' produced by the developed world and their own 'survival emissions', In this way, sociological accounts of international relations and global inequality can clarify some of the underlying causes of the environmental problems we face today.

|

|

Although there are ideas within the work of the classical founders of sociology that have been pursued in an environmental direction by later sociologists, the environment was not a central problem of classical sociology. This situation became increasingly difficult once sociologists began to explore the problems identified by environmental campaigners.

The recent sociological studies of the environment have been characterized by a dispute amongst social constructionist and critical realist approaches over just how environmental issues should be studied sociologically.

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|