Home » Theoretical Perspectives in Sociology

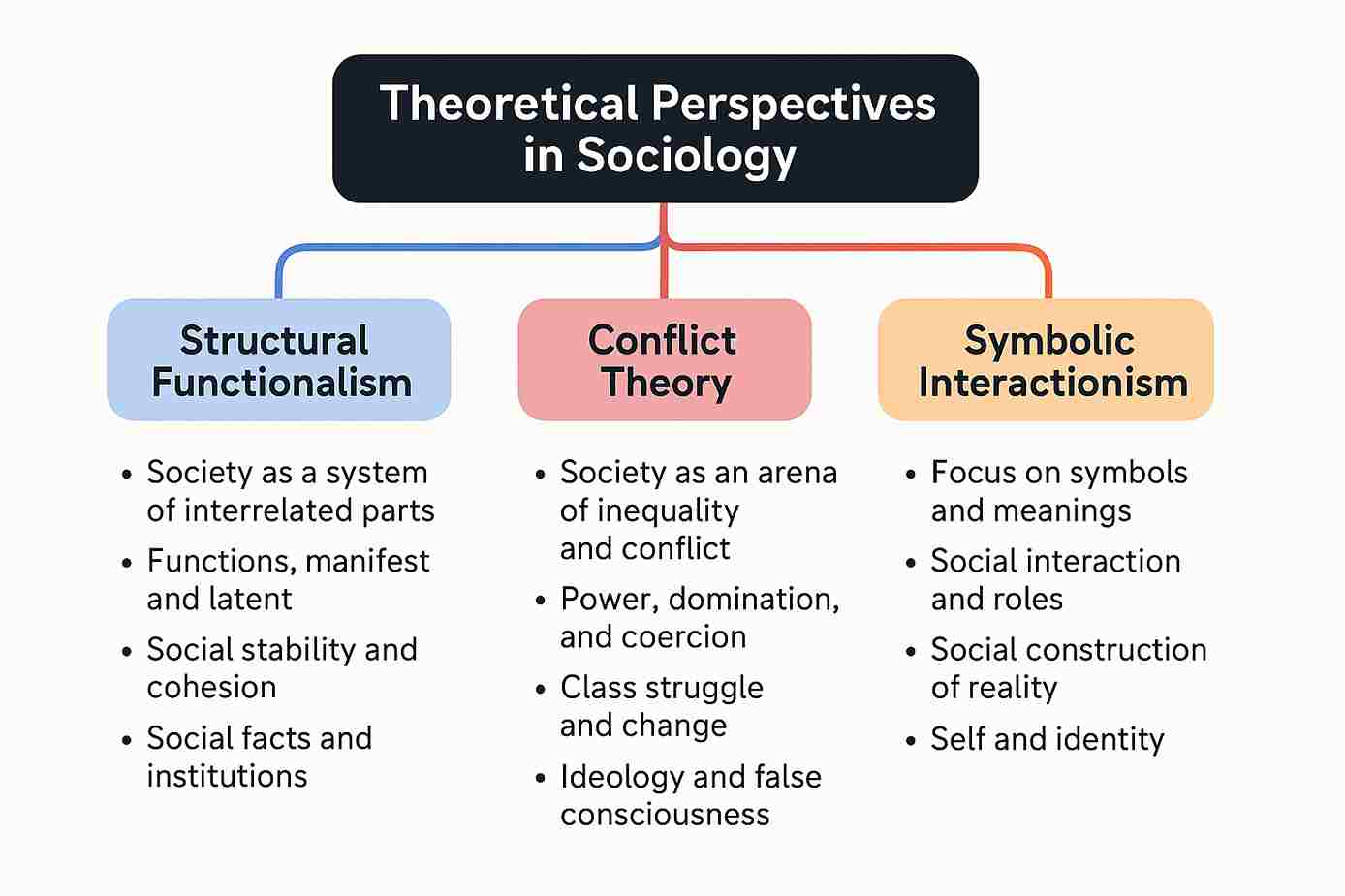

Theoretical Perspectives in Sociology

Structural Functionalism

Structural Functionalism is one of the earliest and most enduring theoretical frameworks in sociology, fundamentally concerned with the structure of society and the functions of its constituent elements. This perspective views society as a complex, interrelated system wherein each part—whether institutions, norms, roles, or values—exists because it contributes to the functioning and equilibrium of the whole. Much like a biological organism, every component of society is seen as working toward the maintenance and stability of the larger system.

The intellectual foundations of this theory lie in the works of Émile

Durkheim, who emphasized that societies are held together by collective

conscience and shared norms. Durkheim’s concept of “social

facts”—norms, values, customs, and institutions that are external to the

individual but exert control over them—highlights the constraining yet

stabilizing nature of social life. For instance, in his classic study Suicide,

Durkheim demonstrated how the act of suicide, typically understood as an

individual decision, varies systematically across social groups due to levels

of integration and regulation—showing that society profoundly shapes

even the most personal behaviors.

In the mid-20th century, Talcott Parsons systematized functionalism into

a grand theory by developing the AGIL schema, identifying four functional

imperatives that any social system must satisfy: Adaptation (A) to the

environment, Goal attainment (G) through decision-making structures,

Integration (I) to ensure cohesion among parts, and Latency (L) for

maintaining cultural patterns and socialization. For example, in modern

society, the economy adapts by distributing resources, the government

attains goals via policymaking, the legal system integrates competing

interests through regulation, and education and family preserve cultural

values across generations.

Robert K. Merton added crucial refinements to this theory by

distinguishing between manifest functions (intended and recognized

outcomes) and latent functions (unintended and hidden consequences). In

the context of schooling, while the manifest function is to impart

knowledge and skills, a latent function might be the reinforcement of

social stratification or peer socialization. Merton also acknowledged the

presence of dysfunctions, thereby introducing nuance to the idea that all

parts of society necessarily contribute positively to stability.

Applied to the Indian context, structural functionalism offers insights into

how institutions like caste, joint family, or Panchayati Raj contributed

historically to maintaining a relatively stable—though hierarchical—social

order. For instance, some early Indian sociologists, such as G.S. Ghurye,

viewed the caste system as a mechanism of division of labor and social

control. However, this perspective has faced major criticism for justifying

inequities under the guise of functionality, especially from Dalit scholars

and subaltern perspectives.

Despite its strengths in emphasizing integration, continuity, and the

interdependence of institutions, structural functionalism has been

critiqued for its conservative bias and inability to account for social

change and conflict. By focusing excessively on stability, it often overlooks

inequalities related to class, caste, gender, or race. Nonetheless, it remains

foundational in sociology for understanding the architecture of social life

and the logic behind institutional arrangements.

Conflict Theory

Conflict theory provides a radically different lens from structural

functionalism by framing society as an arena of contestation, struggle, and

perpetual imbalance. Instead of viewing society as a smoothly functioning

system, conflict theorists see it as structured by asymmetries of power,

wealth, and status, where dominant groups exploit and oppress the

marginalized to maintain their supremacy. The emphasis is not on

consensus or cohesion but on coercion, resistance, and structural

contradictions.

The foundations of conflict theory lie in the revolutionary writings of Karl

Marx, who situated conflict at the core of human history. Marx’s

materialist conception of history asserts that the economic base (the

mode and relations of production) shapes the superstructure (culture, law,

politics, religion), and that the history of all societies is the history of class

struggles. In capitalist society, this struggle unfolds between the

bourgeoisie, who own the means of production, and the proletariat, who

must sell their labor. The capitalist system is sustained through ideological

manipulation and the extraction of surplus value, which creates alienation

and false consciousness among workers. According to Marx, only through

revolutionary praxis can a classless, emancipated society emerge.

Extending Marx’s ideas, C. Wright Mills critiqued the concentration of

power in the hands of a “power elite”—a tightly knit group of military,

political, and corporate leaders whose decisions shape national and global

destinies, often at the cost of democratic participation. Mills emphasized

the role of bureaucracies and institutional control in perpetuating

inequality and curbing dissent.

In the Indian context, conflict theory offers a powerful framework to

analyze caste oppression, landlessness, bonded labor, gender violence, and

communal conflict. The caste system, for instance, can be understood not

as a cultural tradition but as a rigid system of graded inequality, as argued

by B.R. Ambedkar, whose interpretations resonate strongly with conflict

theory. He identified religious texts and cultural norms as tools used by

upper castes to dominate Dalits and rationalize exclusion and violence.

Similarly, class-based farmer protests, tribal resistance against mining

projects, and labor union agitations illustrate the persistent structural

contradictions within Indian society.

Furthermore, Antonio Gramsci’s theory of cultural hegemony deepens

conflict theory by showing how dominant classes maintain control not just

through coercion but by manufacturing consent through media,

education, and religion. In India, for example, media portrayal of urban

slums as sites of criminality and backwardness can be seen as an attempt

to delegitimize the struggles of the poor and justify neoliberal urban

development.

While conflict theory has been critiqued for being overly deterministic,

focusing narrowly on economic dimensions and neglecting identity-based

or cultural struggles, it remains indispensable for unmasking the deep

structures of inequality that shape society. It encourages sociologists to

question the status quo, uncover the interests behind policies, and

envision transformative change.

Symbolic Interactionism

Symbolic interactionism presents a uniquely interpretive and micro-level

approach to sociology, shifting the analytical lens from large-scale

structures to the everyday practices and meanings that individuals create

through interaction. It posits that society is not a static entity but an

ongoing process constructed and reconstructed through human agency,

symbols, and shared understandings.

The intellectual roots of this perspective lie in the work of George Herbert

Mead, who viewed the development of the self as inherently social.

According to Mead, the self emerges through a dialogic process in which

individuals learn to take the role of others—a process that evolves from

imitation to role-play to understanding the generalized other. This

internalization allows individuals to reflect upon themselves as objects of

attention, thus enabling self-regulation and consciousness. Crucially,

Mead argued that communication via significant symbols, especially

language, is the mechanism through which social reality is negotiated.

Herbert Blumer, Mead’s student, synthesized symbolic interactionism into

a formal sociological perspective, outlining its three central premises: (1)

humans act toward things based on the meanings they assign; (2) these

meanings arise out of social interactions; and (3) meanings are constantly

interpreted and modified through ongoing interactions. These principles

emphasize agency, interpretation, and the fluidity of social life.

Erving Goffman, one of the most influential symbolic interactionists,

introduced dramaturgical analysis in his work The Presentation of Self in

Everyday Life. He conceptualized social life as a stage, where individuals

perform roles, manage impressions, and deploy props to maintain social

identity. The division between frontstage (public persona) and backstage

(private self) behavior reveals how individuals navigate complex

expectations in different social settings. For instance, a teacher may

perform authority in the classroom but express vulnerability or frustration

in the staffroom—showing the situational nature of identity.

Symbolic interactionism is particularly insightful in understanding

deviance, stigma, identity formation, and labeling processes. For example,

in schools, a student labeled as “weak” may internalize this identity and

perform poorly—a process known as the self-fulfilling prophecy. Similarly,

Howard Becker’s labeling theory suggests that deviance is not inherent in

any act but is socially constructed through reactions and labels—critical

for understanding issues like drug use, sexuality, or juvenile delinquency.

In the Indian context, this perspective can be applied to analyze how

caste, gender, and religious identities are constructed, performed, and

negotiated. For example, Dalit identity is not simply imposed; it is also

reclaimed and rearticulated through activism, art, and assertion. Similarly,

gender roles in India—such as expectations around modesty, marriage, or

family responsibilities—are performed and reinforced through daily

interactions and symbolic cues like dress, speech, or gesture.

However, symbolic interactionism is often critiqued for its limited scope,

as it tends to neglect structural constraints such as class oppression,

institutional racism, or patriarchy. Yet, its strength lies in illuminating the

granular, interpretive dimension of social life, which often escapes the

purview of grand theories. By focusing on meaning, identity, and the

processual nature of social interaction, it provides a bottom-up

understanding of how society is lived and experienced.

References:

- Durkheim, Émile. (1951). Suicide: A Study in Sociology. Free Press.

- Parsons, Talcott. (1951). The Social System. Free Press.

- Marx, Karl, & Engels, Friedrich. (1848). The Communist Manifesto.

- Mills, C. Wright. (1956). The Power Elite. Oxford University Press.

- Mead, George Herbert. (1934). Mind, Self, and Society. University of Chicago Press.

- Goffman, Erving. (1959). The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Anchor Books.

The present period of sociological theorizing is characterized by a diversity of theoretical approaches and perspectives. Sociological theories are necessary because without theory our understanding of social life would be very weak. Good theories help us to arrive at a deeper understanding of societies and to explain the social changes that affect us all.

A sociological perspective was made possible by two revolutionary transformations. The Industrial Revolution of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries radically transformed the material conditions of life and bringing with it, initially at least, many new social problems such as urban overcrowding, poor sanitation and accompanying disease and industrial pollution on an unprecedented scale.

|

|

Social reformers looked for ways to mitigate and solve such problems, which led them to carry out research and gather evidence on the extent and nature of the problems to reinforce their case for change. The French Revolution of 1789 marked the symbolic endpoint of the older European agrarian regimes and absolute monarchies as republican ideals of freedom, liberty and citizenship rights came to the fore. Enlightenment philosophers saw the advancement of reliable knowledge in the natural sciences, particularly in astronomy, physics and chemistry, as showing the way forward for the study of social life.

- Functionalism

- Conflict Theory

- Structural Functionalism

- Georg Simmel's Theory on Culture

- Social Types

- Theory of Technological Evolutionism

- Veblen's Concept of social change

- Feminist theory

- Understanding Sociology of Sports with Theoretical Perspectives

- Subaltern Perspective

- David Hardiman

- Dr. BR Ambedkar

- Civilizational Perspective

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|