Home >> Basic Concepts >> Acculturation

Acculturation

Index

- Introduction to Acculturation

- Historical Context and Conceptual Origins

- Distinction Between Acculturation and Assimilation

- Theoretical Models of Acculturation

- Psychological and Sociocultural Dimensions

- Biculturalism and Selective Adaptation

- Acculturation in Postcolonial and Global Contexts

- Acculturation in the Indian Context

- Challenges, Resistance, and Cultural Retention

- Conclusion

Introduction to Acculturation

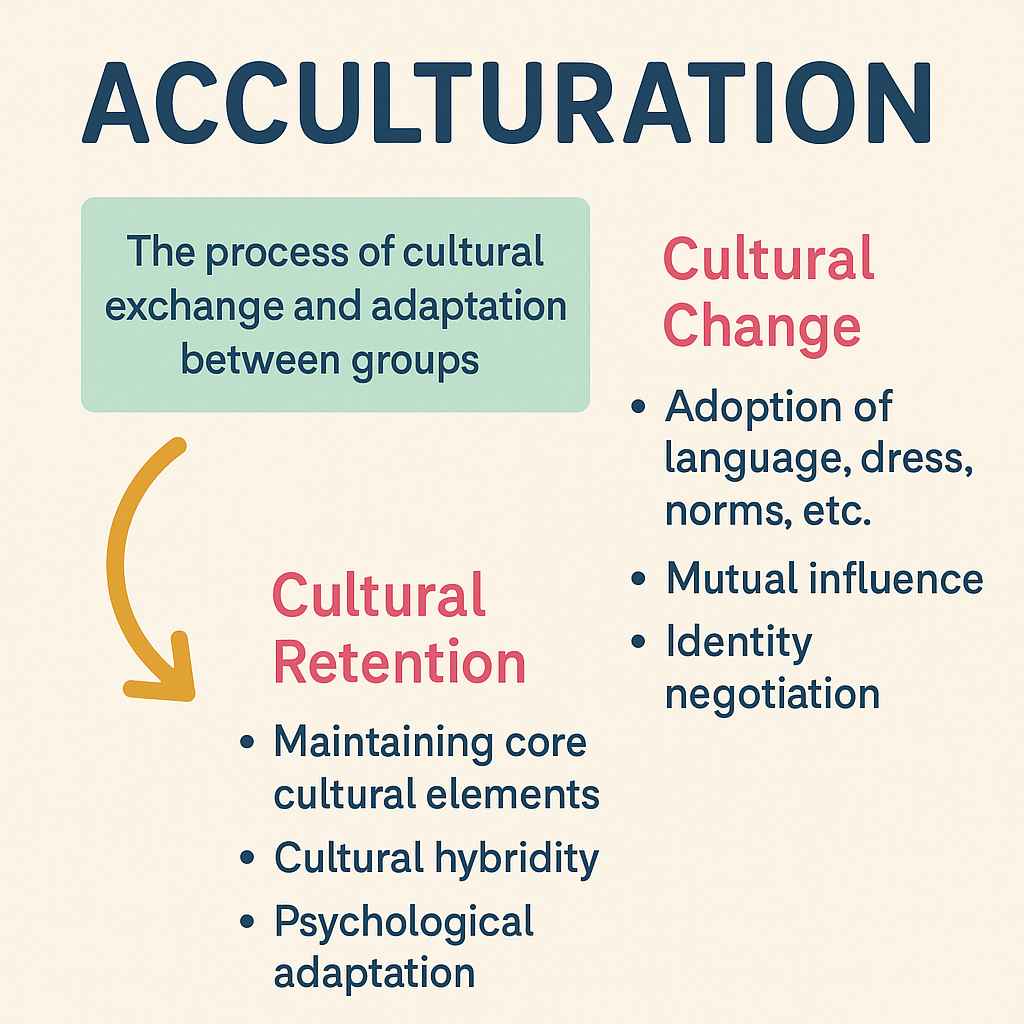

Acculturation is a fundamental sociological and anthropological concept that refers to the process of cultural exchange and adaptation that occurs when individuals or groups from different cultural backgrounds come into continuous, direct contact. Unlike assimilation, which implies a one-sided absorption into a dominant culture, acculturation allows for reciprocal influence—where both the dominant and minority cultures may undergo change. This process involves the acquisition of certain elements of another culture such as language, dress, food habits, and social norms, while retaining aspects of one’s own cultural identity. Acculturation is often studied in contexts of migration, colonialism, globalization, and intergroup relations, and it plays a vital role in understanding how people negotiate identity, belonging, and cultural continuity in changing environments.

Historical Context and Conceptual Origins

The term “acculturation” was first systematically used in anthropology and sociology in the early 20th century, particularly in colonial and post-colonial studies. The Redfield, Linton, and Herskovits definition (1936)—often cited as a foundational reference—describes acculturation as the phenomena that result when groups of individuals having different cultures come into continuous first-hand contact, with subsequent changes in the original cultural patterns of either or both groups. This definition emphasized mutual influence and cultural change rather than cultural loss or absorption. In colonial settings, acculturation was often used to describe how colonized populations adopted certain aspects of European culture, not always out of choice but due to economic, administrative, or educational imposition. However, it also acknowledged that colonizers themselves were not immune to cultural influences from indigenous populations, indicating a two-way dynamic.

Distinction Between Acculturation and Assimilation

It is important to distinguish acculturation from assimilation, though the two are often confused. While assimilation implies complete absorption of a minority group into the dominant group’s cultural norms—usually with the eventual loss of the minority identity—acculturation is a broader, more flexible process. In acculturation, individuals may adopt certain aspects of another culture while retaining their original cultural practices and values. For instance, a migrant community may adopt the dominant language for economic mobility but continue to celebrate traditional festivals, maintain kinship practices, or cook ethnic food. This distinction has major implications for policy, identity politics, and social cohesion. Acculturation accommodates hybridity and dual identities, whereas assimilation often demands conformity and uniformity.

Theoretical Models of Acculturation

Several models have been developed to explain the process of acculturation. One of the most influential is John W. Berry’s model of acculturation (1990), which identifies four possible strategies individuals and groups may adopt: integration, assimilation, separation, and marginalization. Integration occurs when individuals maintain their original culture while also engaging with the host culture; assimilation involves discarding the original culture in favor of the new; separation reflects the rejection of the host culture while maintaining one’s own; and marginalization occurs when individuals lose touch with both their original and host cultures. Berry’s framework highlights the psychological agency involved in navigating cultural boundaries and is widely used in multicultural and migration studies. It also reveals the role of the host society in enabling or constraining these strategies through inclusivity, discrimination, or multicultural policies.

Psychological and Sociocultural Dimensions

Acculturation operates on both psychological and sociocultural levels. On the psychological front, individuals may experience stress, identity conflict, or disorientation—often called acculturative stress—as they navigate between different cultural expectations. This is especially evident among second-generation migrants who may face conflicting loyalties between the traditional values of their parents and the modern values of the society in which they are raised. On the sociocultural level, acculturation affects language use, dress codes, food habits, gender roles, and work ethics. Institutions such as schools, workplaces, and the media play a crucial role in shaping the acculturative process. The success or failure of acculturation often depends on the presence of supportive networks, inclusive policies, and intercultural dialogue.

Biculturalism and Selective Adaptation

Biculturalism is a common outcome of acculturation, particularly among immigrants and diasporic communities. It involves the ability to navigate and function effectively in two cultural environments—retaining one’s heritage while also adapting to the host culture. Bicultural individuals often develop cultural flexibility, bilingualism, and unique identity formations. In practice, this is visible in families where children speak the dominant society’s language at school but use their native language at home. Biculturalism is not merely an individual strategy but can also be seen in the institutional adaptations of communities—such as bilingual education, ethnic festivals, or religious pluralism. Selective adaptation refers to the deliberate adoption of certain features from the dominant culture while rejecting others that conflict with core cultural values, illustrating the agency of acculturating groups.

Acculturation in Postcolonial and Global Contexts

In postcolonial contexts, acculturation is entangled with power dynamics, resistance, and cultural negotiation. Colonized societies were often subject to aggressive cultural transformation through policies of missionary education, Western legal systems, and Christian conversion. However, these societies also responded by selectively incorporating, adapting, or resisting elements of the colonial culture. Post-independence, these hybrid cultural forms became embedded in national identities—e.g., the English language in India or the blending of indigenous and Christian rituals in Africa. In the context of globalization, acculturation has taken on new dimensions. Global media, consumerism, and digital technologies facilitate the rapid transmission of cultural symbols, often creating “global youth cultures” that transcend national boundaries. Yet, even within globalization, local cultures continue to assert themselves, leading to processes of glocalization—a blend of global and local cultures.

Acculturation in the Indian Context

India offers a rich terrain to examine acculturation due to its ethnic, linguistic, and religious diversity. Historically, Indian society has undergone successive waves of acculturation—from Persian and Mughal cultural influences to British colonialism and modern Westernization. Indian Muslims, Christians, and Anglo-Indians have all emerged from such acculturative processes, combining local and foreign cultural elements. Post-independence, urbanization, economic liberalization, and English-medium education have accelerated acculturative exchanges between rural and urban India, and between global and local cultures. For example, Indian middle-class youth frequently engage in global pop culture while retaining strong ties to familial and religious traditions. Among tribal and Dalit communities, acculturation has occurred through educational mobility, religious conversion, or urban migration—often raising questions of authenticity, belonging, and cultural rights.

Challenges, Resistance, and Cultural Retention

While acculturation offers opportunities for cultural enrichment, it also brings challenges—particularly the fear of cultural dilution, loss of heritage, or generational conflict. Migrant parents often worry that their children will lose traditional values in the host culture. At the same time, younger generations may struggle to reconcile the values of their origin culture with those of the society they live in. Resistance to acculturation is not uncommon. Ethnic communities may create cultural enclaves—such as Chinatowns or Punjabi mohallas—to preserve language, food, religion, and customs. Cultural retention becomes a form of identity assertion and a strategy against social marginalization. Community centers, vernacular media, and ethnic institutions play vital roles in sustaining these traditions while still negotiating life in a broader cultural framework.

Conclusion

Acculturation is not a passive or one-dimensional process but a dynamic, negotiated, and often contested practice. It involves the interplay of adaptation, identity, resistance, and hybridization. Sociologists today emphasize the importance of viewing acculturation through an intersectional lens—acknowledging how race, class, gender, religion, and history shape acculturative experiences. The success of acculturation depends not only on the willingness of minorities to adapt but also on the openness of dominant societies to accommodate diversity without coercion. In a world marked by migration, diaspora, and transnational flows, acculturation remains central to understanding how cultural coexistence and social integration unfold in both opportunities and tensions.

References

- Berry, John W. “Acculturation and Adaptation in a New Society.” International Migration, vol. 30, no. 1, 1990, pp. 69–85.

- Redfield, Robert, Ralph Linton, and Melville J. Herskovits. “Memorandum for the Study of Acculturation.” American Anthropologist, vol. 38, no. 1, 1936, pp. 149–152.

- Bhugra, Dinesh. “Migration and Mental Health.” Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, vol. 109, no. 4, 2004, pp. 243–258.

- Kottak, Conrad P. Anthropology: The Exploration of Human Diversity. McGraw-Hill Education, 2016.

This term is used to describe both the process of contacts between different cultures and also the customs of such contacts.

As the process of contact between cultures, acculturation may involve either direct social interaction or exposure to other cultures by means of the mass media of communication.

As the outcome of such contact, acculturation refers to the assimilation by one group of the culture of another which modifies the existing culture and so changes group identity. There may be a tension between old and new cultures which leads to the adapting of the new as well as the old.

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|