Home >> Basic Concepts >> Cultural Lag

Cultural Lag

Index

- Introduction to Cultural Lag

- Origin and Conceptual Development

- William Fielding Ogburn’s Theory of Cultural Lag

- Components of Culture: Material and Non-Material

- Causes and Mechanisms of Cultural Lag

- Consequences of Cultural Lag in Society

- Cultural Lag in the Digital and Technological Age

- Cultural Lag in the Indian Context

- Addressing and Resolving Cultural Lag

- Conclusion

Introduction to Cultural Lag

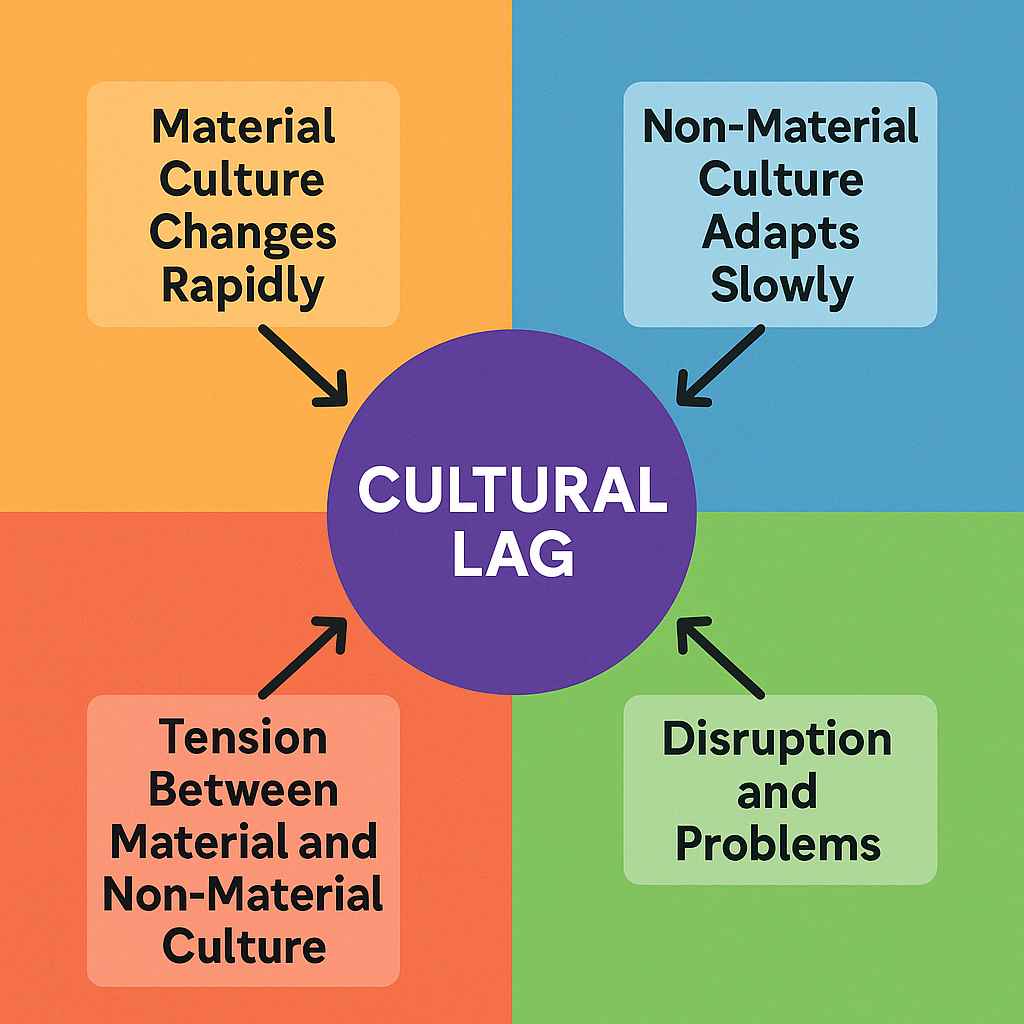

Cultural lag is a key sociological concept that explains the delay or gap between changes in material culture (such as technology or inventions) and the corresponding adjustments in non-material culture (such as beliefs, norms, laws, and values). It highlights the uneven pace at which different aspects of culture evolve, particularly in rapidly transforming societies. Cultural lag becomes a significant issue when society experiences technological or structural changes but struggles to adapt its ethical frameworks, legal systems, or social institutions accordingly. This delay can create confusion, conflict, and maladjustment, making the society vulnerable to moral and institutional crises. The theory of cultural lag is therefore crucial for understanding the tensions between innovation and tradition in social evolution.

Origin and Conceptual Development

The concept of cultural lag was introduced by the American sociologist William Fielding Ogburn in his seminal work Social Change with Respect to Culture and Original Nature (1922). Ogburn argued that culture consists of both material and non-material elements, and that the material elements—such as tools, machines, and inventions—tend to change more rapidly than the non-material components—such as customs, laws, and ethical standards. This time lag creates a dissonance in the cultural system, often manifesting in social problems. Ogburn’s idea was rooted in his broader theory of social change, which emphasized that while technological advancements are the driving force of change, institutions and values often resist change or lag behind, thereby causing tension and dysfunction within the society.

William Fielding Ogburn’s Theory of Cultural Lag

Ogburn’s theory of cultural lag builds on the recognition that cultural change is not uniform. According to him, when new inventions or discoveries occur, they quickly alter the material conditions of life. However, the social institutions and mental habits built around older technologies or cultural forms are not always immediately responsive to these changes. Ogburn provided several examples to illustrate this gap: the development of medical technologies that prolong life, such as ventilators or organ transplants, creates moral and legal dilemmas about euthanasia, end-of-life care, and organ distribution—areas where society is often slow to respond. Thus, cultural lag is not merely a delay but a period of imbalance where material progress has outstripped social readiness or regulatory clarity.

Components of Culture: Material and Non-Material

Understanding cultural lag requires a deeper exploration of the two components of culture: material culture and non-material culture. Material culture includes all the physical, tangible objects created by human beings, such as buildings, tools, machinery, vehicles, and technologies. Non-material culture, on the other hand, encompasses the intangible aspects of a society—its values, norms, beliefs, customs, traditions, legal codes, and symbolic systems. While material culture can be changed or invented rapidly through innovation, non-material culture often evolves slowly due to its embeddedness in social institutions and collective consciousness. This inherent difference in the adaptability of these two components sets the stage for cultural lag when society undergoes rapid technological change.

Causes and Mechanisms of Cultural Lag

Cultural lag is caused by several interrelated factors. Firstly, institutional inertia—the resistance of institutions such as religion, law, and education to change—prevents timely adjustments to new technological realities. Secondly, value conflicts often arise when new technologies challenge existing moral or ethical frameworks, leading to societal debate and hesitation. Thirdly, lack of awareness or understanding of new innovations can prevent their social acceptance or integration. Finally, economic or political interests may delay cultural adaptation when powerful groups resist change to maintain control. These factors ensure that non-material culture—especially values, laws, and norms—often lags behind material developments, leading to a period of social disorganization or contradiction.

Consequences of Cultural Lag in Society

The phenomenon of cultural lag can lead to a wide range of social consequences. It can create legal ambiguities, as institutions struggle to legislate around new realities. For instance, the rise of artificial intelligence and data collection has outpaced the creation of adequate privacy laws, creating ethical and legal dilemmas. Cultural lag can also result in identity crises, especially among youth who grow up immersed in new technological cultures that conflict with older value systems. It contributes to social anxiety, generational conflicts, and policy vacuums. Moreover, it can aggravate social inequality, as some groups adapt quickly to new technologies while others are left behind, widening the digital and cultural divide.

Cultural Lag in the Digital and Technological Age

In the contemporary era, cultural lag is more visible than ever before, especially in the context of digital technologies, biotechnology, and artificial intelligence. The rapid proliferation of smartphones, social media, genetic engineering, and automation has created complex ethical, psychological, and legal questions. For example, technologies like facial recognition and predictive policing raise concerns about surveillance and privacy, but laws and public understanding have not caught up. Similarly, the widespread use of dating apps has restructured social relationships, yet traditional notions of romance, marriage, and morality often lag behind. In this environment, cultural lag becomes a persistent condition, not just a temporary phase, as the speed of material innovation continues to accelerate.

Cultural Lag in the Indian Context

In India, cultural lag is clearly observable in the way society grapples with the implications of modernization and globalization. One of the most visible examples is the status of women. While legal and economic reforms have improved women’s access to education and employment, traditional gender norms regarding marriage, domestic responsibilities, and sexuality often lag behind, leading to conflicts and contradictions. Another example is the digital revolution—while digital payments and online education have expanded rapidly, many rural areas still lack infrastructure and digital literacy. The introduction of new reproductive technologies like IVF or surrogacy also brings legal and ethical dilemmas in a society deeply rooted in caste, kinship, and religious values. These examples reflect how the uneven pace of material and non-material cultural change produces tension within Indian society.

Addressing and Resolving Cultural Lag

Addressing cultural lag requires proactive cultural adaptation through education, policy reform, and ethical deliberation. It involves recognizing the value of interdisciplinary dialogue—between technologists, ethicists, sociologists, and policymakers—to ensure that social institutions evolve alongside technological developments. Civic education can play a role in preparing citizens to navigate new realities, while flexible and inclusive legal frameworks can help resolve moral dilemmas without alienating traditional values. Bridging the cultural lag also requires sensitive leadership that can mediate between innovation and convention, facilitating consensus rather than conflict. Ultimately, minimizing cultural lag is about harmonizing the pace of material and moral progress to promote sustainable and inclusive development.

Conclusion

Cultural lag is not merely a technical term but a profound lens through which sociologists can analyze the fractures and transitions within modern societies. It reveals the fragility of social equilibrium in the face of innovation and underscores the importance of cultural sensitivity in technological advancement. As societies across the globe become increasingly interconnected and technologically advanced, the challenge of cultural lag will intensify. Understanding and addressing it is essential for creating a world where innovation does not outpace human values, and where material advancement is guided by ethical and institutional wisdom. Thus, cultural lag remains a vital concept in the sociology of change, modernity, and development.

References

- Ogburn, William F. Social Change with Respect to Culture and Original Nature. B.W. Huebsch, 1922.

- Rogers, Everett M. Diffusion of Innovations. Free Press, 2003.

- Kornblum, William. Sociology in a Changing World. Cengage Learning, 2011.

- Inkeles, Alex. What Is Sociology? Prentice Hall, 1964.

The role played by material inventions, that is, by technology, in social change probably received most emphasis in the work of William F. Ogburn. It was Ogburn, also, who was chiefly responsible for the idea that the rate of invention within society is a function of the size of the existing culture base. He saw the rate of material invention as increasing with the passage of time.Ogburn believed that material and non-material cultures change in different ways. Change in material culture is believed to have a marked directional or progressive character. This is because there are agreed-upon standards of efficiency that are used to evaluate material inventions. To use air-planes, as an example, we keep working to develop planes that will fly, higher and faster, and carry more payloads on a lower unit cost. Because airplanes can be measured against these standards, inventions in this area appear rapidly and predictably. In the area of non-material culture, on the other hand there often are no such generally accepted standards. Whether one prefers a Hussain, a Picasso, or a Gainsborough, for example, is a matter of taste, and styles of painting fluctuate unevenly. Similarly, in institutions such as government and the economic system there are competing forms of styles, Governments may be dictatorships, oligarchies, republics or democracies.

Economic system includes communist, socialist, feudal, and capitalist ones. As far as can be told, there is no regular progression from one form of government or economic system to another. The obvious directional character of change in material culture is lacking in many areas of non-material culture. In addition to the difference in the directional character of change, Ogburn and others believe that material culture tends to change faster than non-material culture. Certainly one of the imperative aspects of modern American life is the tremendous development of technology. Within this century, life has been transformed by invention of the radio, TV, automobiles, airplanes, rockets, transistors, and computers and so on. While this has been happening in material culture, change in government, economic system, family life, education, and religion seems to have been much slower. This difference in rates of cultural change led Ogburn to formulate the concept of culture lag. Material inventions, he believed bring changes that require adjustments in various areas of non-material culture.Invention of the automobile, for instance, freed young people from direct parental observation, made it possible for them to work at distances from their homes, and, among other things, facilitated crime by making escape easier. Half a century earlier, families still were structured as they were in the era of the family farm when young people were under continuous observation and worked right on the homestead.

Culture lag is defined as the time between the appearance of a new material invention and the making of appropriate adjustments in corresponding area of non-material culture. This time is often long. It was over fifty years, for example, after the typewriter was invented before it was used systematically in offices. Even today, we may have a family system better adapted to a farm economy than to an urban industrial one, and nuclear weapons exist in a diplomatic atmosphere attuned to the nineteenth century. As the discussion implies, the concept of culture lag is associated with the definition of social problems. Scholars envision some balance or adjustment existing between material and non-material cultures. That balance is upset by the appearance of raw material objects. The resulting imbalance is defined as a social problem until non-material culture changes in adjustment to the new technology.

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|