Max Weber

Max Weber (1864-1920) stands as one of the founding fathers of modern sociology and a pivotal gure in understanding the relationship between culture, economy, and social organization. Born into a politically active German family, Weber initially trained as a lawyer and economist before developing his groundbreaking sociological theories. His intellectual journey was marked by a profound mental health crisis in his thirties, after which he produced his most inuential works. Weber’s scholarship fundamentally shaped how we understand modern society, bureaucracy, and the role of religion in economic development.

Weber’s intellectual background was deeply rooted in German academic traditions, drawing from philosophy, history, economics, and law. He was inuenced by the methodological debates of his time, particularly the distinction between natural and social sciences. His approach emphasized verstehen (interpretive understanding) rather than mere empirical observation, arguing that social scientists must comprehend the subjective meanings that individuals attach to their actions.

His major works include “The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism,” which explored how Protestant values fostered capitalist development, and “Economy and Society,” his comprehensive analysis of social organization and authority. Weber developed inuential concepts including ideal types, the three forms of legitimate authority (traditional, charismatic, and legal-rational), and theories of bureaucracy. His work on social stratication, methodology, and comparative religion continues to inuence contemporary social science, making him essential reading for understanding modern society’s complexities.

Verstehen (Interpretative Understanding)

Verstehen represents Weber’s methodological approach to understanding social phenomena through interpretive comprehension rather than mere external observation. This concept distinguishes social sciences from natural sciences by emphasizing the need to understand the subjective meanings that individuals attach to their actions. Weber argued that social scientists must go beyond describing what people do to understand why they do it from their own perspective. This involves two levels of understanding:

- Direct Observational Understanding: Grasping the immediate meaning of an action, such as recognizing that someone is chopping wood or calculating mathematical problems

- Explanatory Understanding: Comprehending the motives and context behind actions, understanding why someone is chopping wood (perhaps to heat their home or earn money) or why they’re doing calculations (maybe for work or study).

Verstehen requires empathetic insight while maintaining scientific objectivity. Weber insisted that understanding subjective meanings doesn’t mean the researcher must agree with or personally experience the same motivations. Instead, they must intellectually grasp how actions make sense within the actor’s frame of reference. This methodology acknowledges that human behavior is fundamentally different from natural phenomena because it involves conscious intention, cultural meaning, and symbolic interpretation.

Social scientists must therefore develop methods appropriate to studying meaningful human action rather than simply applying natural science techniques to social phenomena.

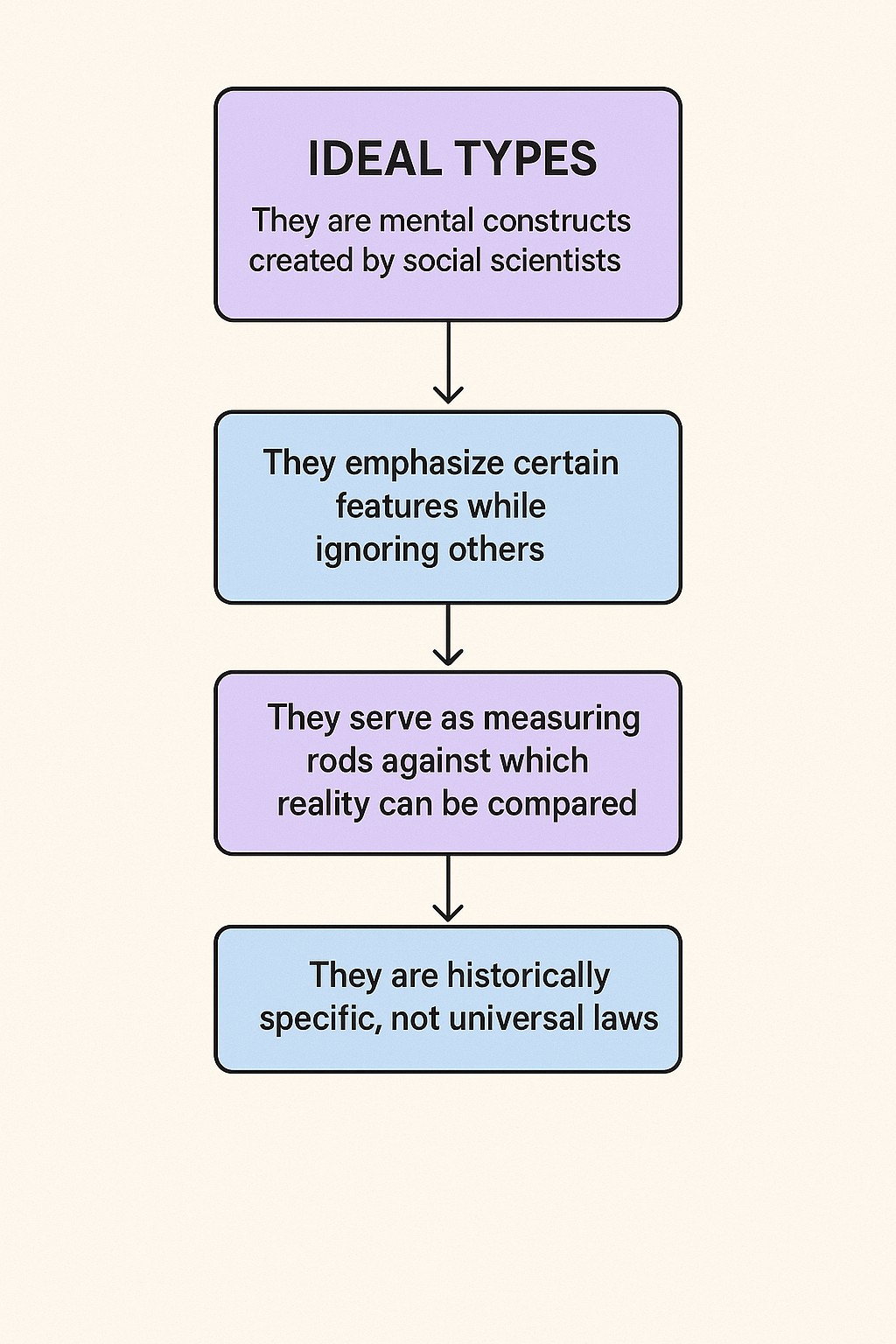

Ideal Types

Ideal types are analytical constructs that Weber developed as methodological tools for understanding and comparing complex social phenomena. They are not “ideal” in the sense of being perfect or desirable, nor are they direct descriptions of reality. Instead, they are deliberately one-sided, exaggerated conceptual models that highlight certain aspects of social reality for analytical purposes.

Characteristics of Ideal Types:

- They are mental constructs created by social scientists

- They emphasize certain features while ignoring others

- They serve as measuring rods against which reality can be compared

- They help identify causal relationships and patterns

- They are historically specific, not universal laws

Construction Process: Weber created ideal types by selecting and accentuating certain elements of observed phenomena, combining them into logically consistent, coherent concepts. For example, his ideal type of bureaucracy emphasizes formal rules, hierarchy, and impersonality, even though real bureaucracies may have informal networks and personal relationships.

Functions of Ideal Types:

Analytical: They help break down complex social phenomena into manageable components

Comparative: They enable comparison across different societies and historical periods

Explanatory: They help identify which factors are most important in causing social outcomes

Predictive: They suggest what might happen under certain conditions

Examples include Weber’s ideal types of authority, capitalism, bureaucracy, and various religious orientations. These tools allowed Weber to analyze how real-world phenomena deviated from or approximated these constructed models, thereby revealing important social dynamics and causal relationships.

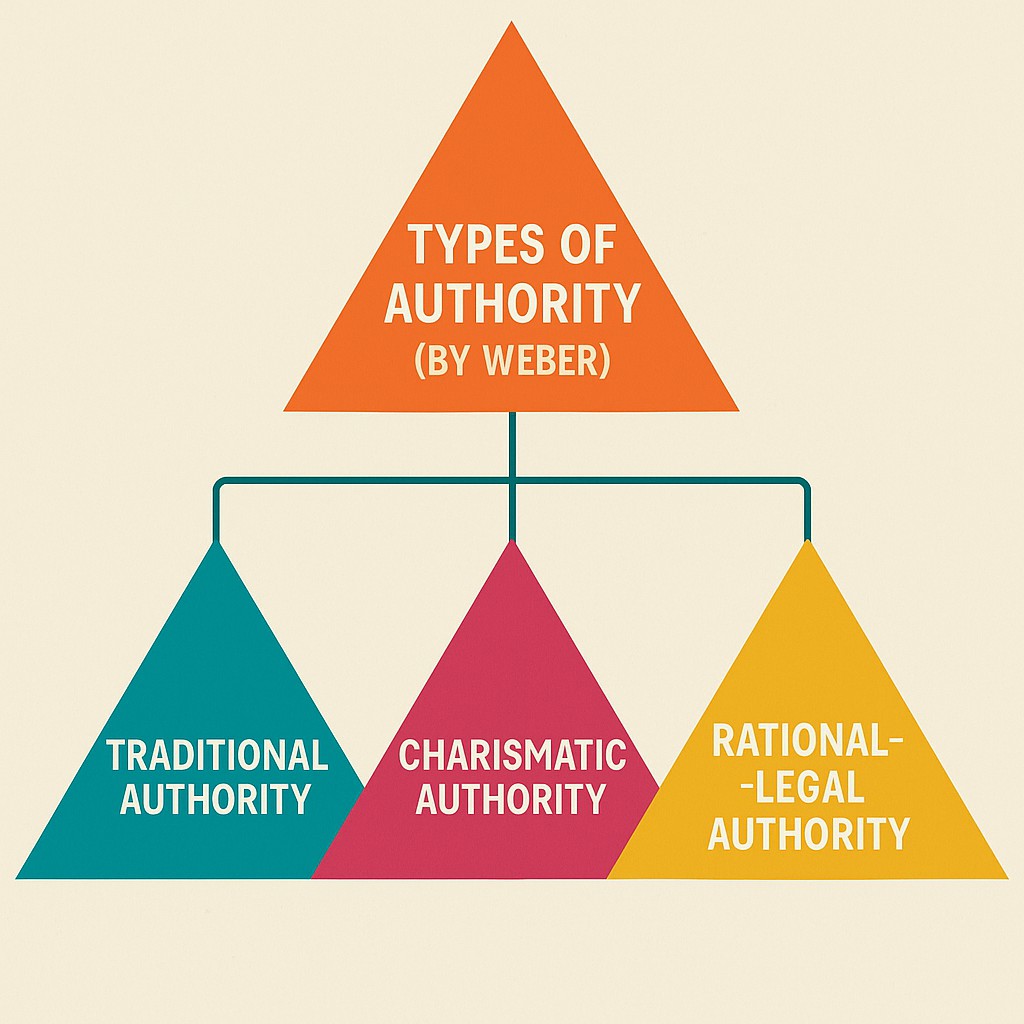

Types of Authority

Weber’s analysis of authority focuses on the grounds upon which people consider domination legitimate. He identified three pure types of legitimate authority, each based on different sources of legitimacy:

Traditional Authority is based on the sanctity of age-old rules and powers. Legitimacy derives from custom, precedent, and the belief that things should continue as they always have been. Traditional leaders possess authority because of their inherited status or position within established social structures. Characteristics include personal loyalty to the traditional leader, authority transmitted through inheritance or established succession rules, and administrative staff consisting of personal dependents, relatives, or traditional elites. Examples include monarchies, feudal systems, patriarchal families, and tribal chieftains.

The leader’s power is often limited by traditional constraints and precedents, but within those bounds, their authority may be quite extensive.

Charismatic Authority rests on the exceptional personal qualities of an individual leader. Followers believe the leader possesses supernatural, superhuman, or extraordinary powers, making them worthy of devotion and obedience. This authority is highly personal and emotional. Key features include devotion to the specific person of the leader, administrative staff chosen based on personal loyalty and charismatic qualification rather than technical expertise, and revolutionary potential that can challenge existing traditional or legal structures. Examples include religious prophets, revolutionary leaders, war heroes, and transformational political figures like Gandhi or Martin Luther King Jr.

Charismatic authority faces the fundamental problem of succession since it depends on the unique qualities of one individual. Weber identified several ways charismatic authority might be routinized: through search procedures for a new charismatic leader, hereditary transmission, or institutional transformation into traditional or legal-rational forms.

Legal-Rational Authority is based on a belief in the validity of legal rules and the right of those elevated to authority under such rules to issue commands. Legitimacy comes from adherence to formally correct procedures and abstract rules rather than personal qualities or traditions.

Characteristics include obedience to impersonal rules rather than persons, authority holders appointed based on technical qualifications, clearly defined spheres of competence and responsibility, and systematic administration through bureaucratic organization. Modern democratic governments, corporate hierarchies, and professional organizations exemplify legal-rational authority. This form of authority is closely linked to Weber’s concept of rationalization and the development of modern society. It enables large-scale, complex organizations to function efficiently while maintaining predictability and fairness through rule-based procedures.

IRON CAGE

Weber’s “iron cage” of bureaucracy represents his profound concern about the dehumanizing effects of modern rational organization. This metaphor describes how bureaucratic structures, while technically efficient, can trap individuals in rigid, impersonal systems that limit human freedom and creativity.

The iron cage emerges from the rationalization process that Weber saw as defining modern society. As organizations become increasingly bureaucratized, they prioritize formal rules, procedures, and efficiency over individual needs and values. People become cogs in a vast administrative machine, bound by regulations and hierarchical structures that dictate their behavior regardless of personal preferences or circumstances.

Weber argued that bureaucracy’s very strengths—predictability, impartiality, and efficiency—become sources of oppression. Individuals must conform to standardized procedures, suppress personal judgment, and operate within narrowly defined roles. The system becomes self-perpetuating as bureaucratic logic spreads throughout society, from government agencies to corporations to educational institutions.

This creates what Weber called the “polar night of icy darkness”—a world where technical rationality dominates but spiritual and ethical considerations are marginalized. People lose autonomy and become dependent on bureaucratic systems for their livelihood and identity. The cage is “iron” because escape seems impossible; modern life requires participation in these rational organizations.

Weber’s iron cage concept presciently anticipated contemporary concerns about corporate culture, government regulation, and institutional conformity, highlighting the tension between organizational efficiency and human dignity in modern society.

Rationalization

Weber’s concept of rationalization represents his central theory explaining the fundamental transformation of Western civilization from traditional to modern society. He viewed rationalization as an irreversible historical process where social life becomes increasingly dominated by efficiency, calculability, predictability, and systematic control through formal rules and scientific methods.

Rationalization manifests in multiple dimensions. Theoretical rationalization involves the “disenchantment of the world”—the replacement of magical and religious explanations with scientific understanding and logical thinking. Practical rationalization organizes daily life according to calculated procedures designed to achieve specific goals efficiently, evident in capitalist economics, legal systems, and bureaucratic administration.

Weber distinguished between formal rationality (focused on efficiency and calculability) and substantive rationality (oriented toward ultimate values and ethical principles). He observed formal rationality increasingly dominating modern life, often at the expense of meaningful values and personal freedom.

The rationalization process transforms all spheres of society: economic life becomes dominated by market calculations, religious belief evolves toward systematic theology, legal systems develop codified rules, and political authority becomes bureaucratized. While rationalization enables unprecedented organizational achievements and human control over the environment, Weber warned of its darker consequences—the potential creation of an “iron cage” where technical efficiency undermines human creativity, spontaneity, and spiritual meaning, trapping individuals in impersonal, bureaucratic systems that prioritize procedure over humanity.

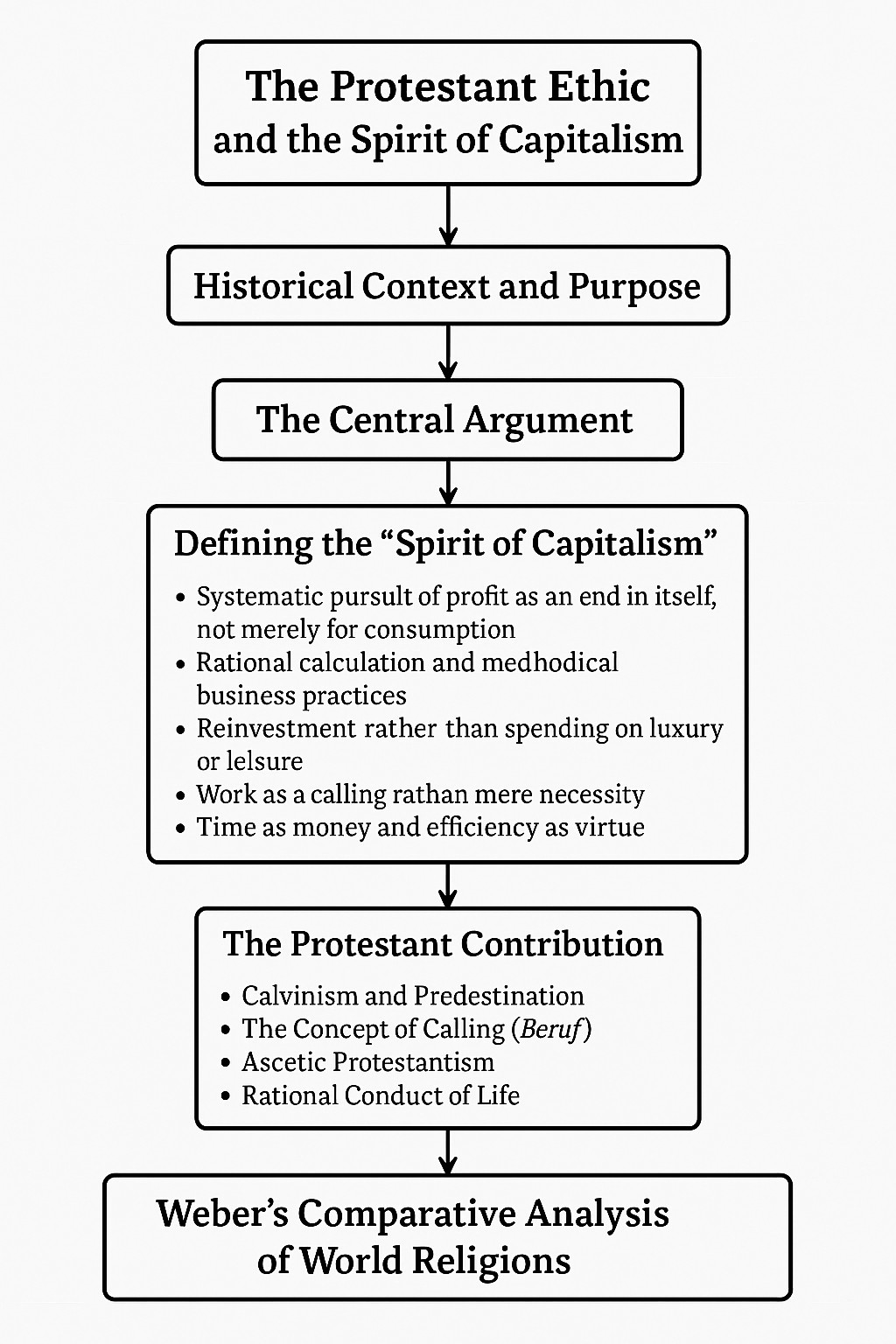

The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism

Historical Context and Purpose

Weber’s “The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism” (1905) emerged during intense debates about the origins of modern capitalism. Marx and other materialist thinkers argued that economic structures determined cultural and religious beliefs. Weber sought to demonstrate the reverse causal relationship—how ideas, particularly religious ones, could shape economic development. He aimed to show that culture and religion possessed independent causal power in historical change.

Weber wasn’t arguing that Protestantism caused capitalism, but rather that certain Protestant beliefs created cultural conditions particularly favorable to capitalist development. This represented a crucial intervention in understanding the relationship between material and ideal factors in social transformation.

The Central Argument

The Problem Weber Addressed

Weber observed that capitalism emerged most vigorously in Protestant regions of Europe rather than Catholic areas, despite Catholics often having superior commercial infrastructure and educational systems. This geographic correlation demanded explanation beyond purely economic factors.

Defining the “Spirit of Capitalism”

Weber distinguished between capitalism as an economic system (which existed in various forms throughout history) and the specific “spirit” of modern capitalism. This spirit embodied:

- Systematic pursuit of profit as an end in itself, not merely for consumption

- Rational calculation and methodical business practices

- Reinvestment rather than spending on luxury or leisure

- Work as a calling rather than mere necessity

- Time as money and efficiency as virtue

This capitalist ethos represented a revolutionary departure from traditional economic attitudes that viewed wealth accumulation with suspicion and prioritized social status over profit maximization.

The Protestant Contribution

Weber identified several Protestant denominations—particularly Calvinism, Pietism, Methodism, and Baptist sects—as crucial in fostering capitalist attitudes. Each contributed specific elements:

Calvinism and Predestination: Calvin’s doctrine of predestination created profound psychological tension. Believers couldn’t know whether God had chosen them for salvation, leading to desperate searches for signs of divine grace. Worldly success became interpreted as evidence of divine favor.

The Concept of Calling (Beruf): Protestant theology transformed work from mere necessity into religious duty. Luther’s translation of the Bible introduced the concept of worldly work as a “calling” from God, sanctifying ordinary economic activity with religious significance.

Ascetic Protestantism: These denominations promoted “inner-worldly asceticism”—rigorous self-discipline applied to worldly activities rather than monastic withdrawal. This created systematic, methodical approaches to economic life.

Rational Conduct of Life: Protestant emphasis on self-examination, systematic behavior, and moral accountability fostered rational, calculated approaches to all aspects of life, including economic activity.

Weber’s Comparative Analysis of World Religions

Weber’s broader project involved comparative analysis of major world religions to understand their different relationships with economic development.

Hinduism and the Caste System

Weber argued that Hinduism’s caste system inhibited capitalist development through:

- Ritual purity concerns that prevented certain economic activities

- Karma doctrine that encouraged acceptance of existing social positions

- Otherworldly orientation that devalued material success

- Caste restrictions that limited occupational mobility and rational economic organization

Buddhism and World Rejection

Buddhism’s emphasis on suffering as inherent to existence and the goal of escaping worldly attachments created:

- Otherworldly mysticism incompatible with systematic economic activity

- Devaluation of material pursuits as obstacles to enlightenment

- Monastic ideals that withdrew the most dedicated practitioners from economic life

Confucianism and Traditional China

Despite China’s sophisticated culture and technology, Confucianism didn’t generate capitalist development because:

- Emphasis on tradition and harmony discouraged innovation

- Bureaucratic ideals that valued literary education over practical economic skills

- Family-centered ethics that prioritized kinship obligations over rational economic calculation

- Lack of transcendent tension that might motivate systematic transformation of the world

Judaism and Economic Activity

Weber noted that while Jews often engaged in commerce, their religious orientation differed from Protestant capitalism:

- Pariah status that channeled economic activity into specific sectors

- Dual ethics that distinguished between in-group and out-group economic relationships

- Ritual concerns that limited certain types of economic activity

- Messianic expectations that maintained otherworldly orientation

Weber’s Theory of Religion

Religion as Meaning-Making

Weber viewed religion as humanity’s fundamental response to existential questions about suffering, death, and meaning. Religious systems provide:

Theodicies: explanations for why suffering exists

Salvation concepts: pathways to overcoming fundamental human problems

Ethical frameworks: guidelines for proper conduct

Community structures: social organization around shared beliefs

The Rationalization of Religion

Weber traced religion’s evolution from magical thinking toward increasingly systematic theological and ethical systems. This process involved:

- Differentiation of religious specialists from ordinary practitioners

- Systematization of beliefs into coherent theological frameworks

- Ethicalization of religious demands beyond mere ritual observance

- Universalization of religious messages beyond particular tribes or groups

Religion and Social Stratification

Different social classes developed distinct religious orientations:

- Warrior classes preferred religions emphasizing honor, fate, and heroic action

- Peasant classes remained attached to magical, naturalistic religious practices

- Urban commercial classes developed ethical religions emphasizing systematic conduct

- Intellectual classes created sophisticated theological and philosophical systems

Charisma and Routinization

Weber’s analysis of religious development emphasized the tension between:

- Charismatic origins: religions typically begin with extraordinary individuals claiming divine revelation

- Routinization pressures: as movements grow, they must develop stable institutions and procedures

- Bureaucratization: mature religious organizations become increasingly rationalized and bureaucratic

Elective Affinity

Weber’s concept of “elective affinity” explained how certain religious beliefs naturally aligned with particular economic orientations without direct causal determination. Protestant ethics and capitalist spirit had mutual affinity because both emphasized:

- Systematic, methodical conduct

- Rational calculation and planning

- Individual responsibility and achievement

- Disciplined self-control

- Productive use of time and resources

This affinity meant that Protestant beliefs and capitalist practices mutually reinforced each other, creating powerful historical momentum.

Contemporary Relevance

Max Weber’s work remains highly relevant in understanding contemporary society, especially in the context of capitalism, bureaucracy, and the role of ideas in shaping social structures. His concept of the “Protestant ethic” helps explain how cultural and religious values can influence economic behavior even today. In an age where efficiency, time management, and individual achievement are central to workplace culture, Weber’s insights into the “spirit of capitalism” are more pertinent than ever.

His analysis of bureaucracy is vital for understanding modern institutions—government, corporations, and NGOs alike. Weber’s idea of rational-legal authority explains the functioning of bureaucracies that dominate today’s political and economic systems. Moreover, his concept of the “iron cage” highlights the risks of excessive rationalization, where human values may be lost in rigid structures and efficiency-driven goals.

In today’s multicultural world, Weber’s comparative analysis of world religions helps interpret how belief systems influence social and economic behaviors across cultures. His methodology—verstehen (interpretive understanding)—is also central to qualitative social research, encouraging empathy and depth in studying human action.

Overall, Weber’s theories continue to inform debates on modernity, development, governance, and the intersection of culture and economy in a globalized world.

References

Weber, M. (1978). Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology (G. Roth & C. Wittich, Eds.). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Weber, M. (2002). The Protestant Ethic and the “Spirit” of Capitalism (S. Kalberg, Trans.). Los Angeles: Roxbury Publishing Company. (Original work published 1905)

Action is social if some meaning is attached to it by the actor, i.e the actor must be conscious of his or her action. The meanings are in the form of motivation of an individual which is her or his own subjective state. Weber rejected the independent influence of the values on individuals rather the values are interpretated by the actor, according to his or her motivation and according to that an action is taken.

|

|

Action is social if it is oriented to some other, i.e. only those actions are social which are taken in orientation to some other object. The orientation can be physical or mental, the other person may or may not be present in a social action. Weber also differentiated between action and behavior. Behavior is a biological concept and is spontaneous in nature with no attachment of meaning. According to Weber, the establishment of cause and effect should be the aim of sociology. Understanding the meanings attached by the actors to their actions can only help us to establish cause and effect relationships.

|

© 2025 sociologyguide |

|

Max Weber’s Key Sociological Concepts

Social Action and Its Types

Weber defined social action as human behavior that is meaningfully oriented toward others and takes their likely responses into account. This forms the foundation of his sociology, distinguishing mere behavior from social action by emphasizing subjective meaning and social orientation.

Weber identified four ideal types of social action:

Zweckrational (Instrumental Rational Action): Action oriented toward achieving specific goals through calculated means. The actor weighs different methods and consequences to achieve desired outcomes efficiently. For example, a businessperson choosing the most cost-effective production method to maximize profits.

Wertrational (Value Rational Action): Action guided by absolute values, beliefs, or ethical principles, regardless of consequences. The actor commits to certain values unconditionally. Examples include religious devotion, honor-bound behavior, or principled political activism where the actor follows their convictions despite potential negative outcomes.

Affectual Action: Action driven by emotions, feelings, or psychological states. This includes spontaneous reactions based on love, hate, anger, or joy. A person comforting a crying child or lashing out in anger exemplifies affectual action.

Traditional Action: Action guided by customs, habits, and established practices passed down through generations. People act this way because “it has always been done.” Examples include religious rituals, cultural ceremonies, or following inherited family traditions.

Weber emphasized that these are analytical categories, and real social actions often combine multiple types simultaneously.