Home >> Research Methods and Statistics

Research Methods and Statistics

Index

- Introduction: Nature and Importance of Social Research

- Philosophical Foundations: Positivism and Anti-Positivism

- Scientific Method and its Sociological Application

- Types of Social Research: Basic, Applied, Action, and Evaluative

- Research Design and Formulation of Research Problem

- Methods of Data Collection: Quantitative and Qualitative

- Sampling Methods: Probability and Non-Probability

- Scaling Techniques: Likert, Guttman, and Thurstone

- Tools of Data Collection: Interview, Questionnaire, Schedule, Observation

- Data Processing and Classification

- Measures of Central Tendency: Mean, Median, Mode

- Correlation and Regression

- Tests of Significance: t-test, Chi-square

- Report Writing and Ethics in Research

- Contemporary Issues in Research: Digital Tools and Big Data

- Conclusion

1. Introduction: Nature and Importance of Social Research

Social research lies at the heart of sociological inquiry. It provides the methodological

foundation for understanding society, institutions, and human behavior using

systematic, empirical, and analytical procedures. Unlike common sense, which often

relies on assumptions, hearsay, or personal experiences, social research seeks to

uncover patterns, relationships, and meanings through observation, measurement,

and reasoning. In essence, research allows sociologists to convert abstract ideas into

testable propositions and contributes to building, modifying, or rejecting theories.

The fundamental objective of social research is not only to explain existing social

phenomena but also to predict and control future occurrences by identifying causal

links and mechanisms. For example, understanding the reasons for high dropout

rates among rural students in India requires an empirical investigation of social class,

gender norms, economic hardship, and institutional quality—insights that are

impossible through anecdotal observations alone. Thus, research transforms

sociology from a philosophical speculation into a disciplined scientific enterprise.

Sociological research is inherently embedded within the socio-cultural context in

which it operates. The questions asked, the methods employed, and the

interpretations drawn are all influenced by the researcher’s location, worldview, and

purpose. Social research can be conducted to fulfill various needs: it can generate new

knowledge, inform public policy, improve social services, or give voice to

marginalized communities. In India, research has played a pivotal role in evaluating

programs like the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act

(MGNREGA), understanding caste discrimination, assessing gender violence, and

mapping urban poverty. In this way, social research contributes directly to

democratic planning and nation-building. Moreover, it helps sociologists maintain a

critical stance toward ideology, power, and domination by grounding claims in

evidence rather than opinion. A systematic approach to research also builds

cumulative knowledge, wherein each study builds upon or contests previous work,

facilitating academic dialogue and progress.

In today’s data-driven world, research has become even more central. The explosion

of digital technologies, artificial intelligence, and big data analytics has opened new

frontiers in both the scale and scope of social inquiry. Surveys can now reach millions

of respondents through online platforms; mobile tracking allows researchers to

understand real-time mobility patterns; social media content offers rich insights into

public opinion. However, these developments also introduce new ethical and

methodological challenges. Issues of privacy, consent, data ownership, and

algorithmic bias necessitate a renewed ethical commitment in the practice of social

research. Hence, the importance of scientific temper, methodological rigor, and

ethical sensitivity cannot be overstated in the contemporary era of automation and

information overload. Research methods and statistics, therefore, provide the

essential tools through which sociologists navigate the complex terrain of social life

and produce knowledge that is not only robust and reliable but also socially

meaningful and politically responsible.

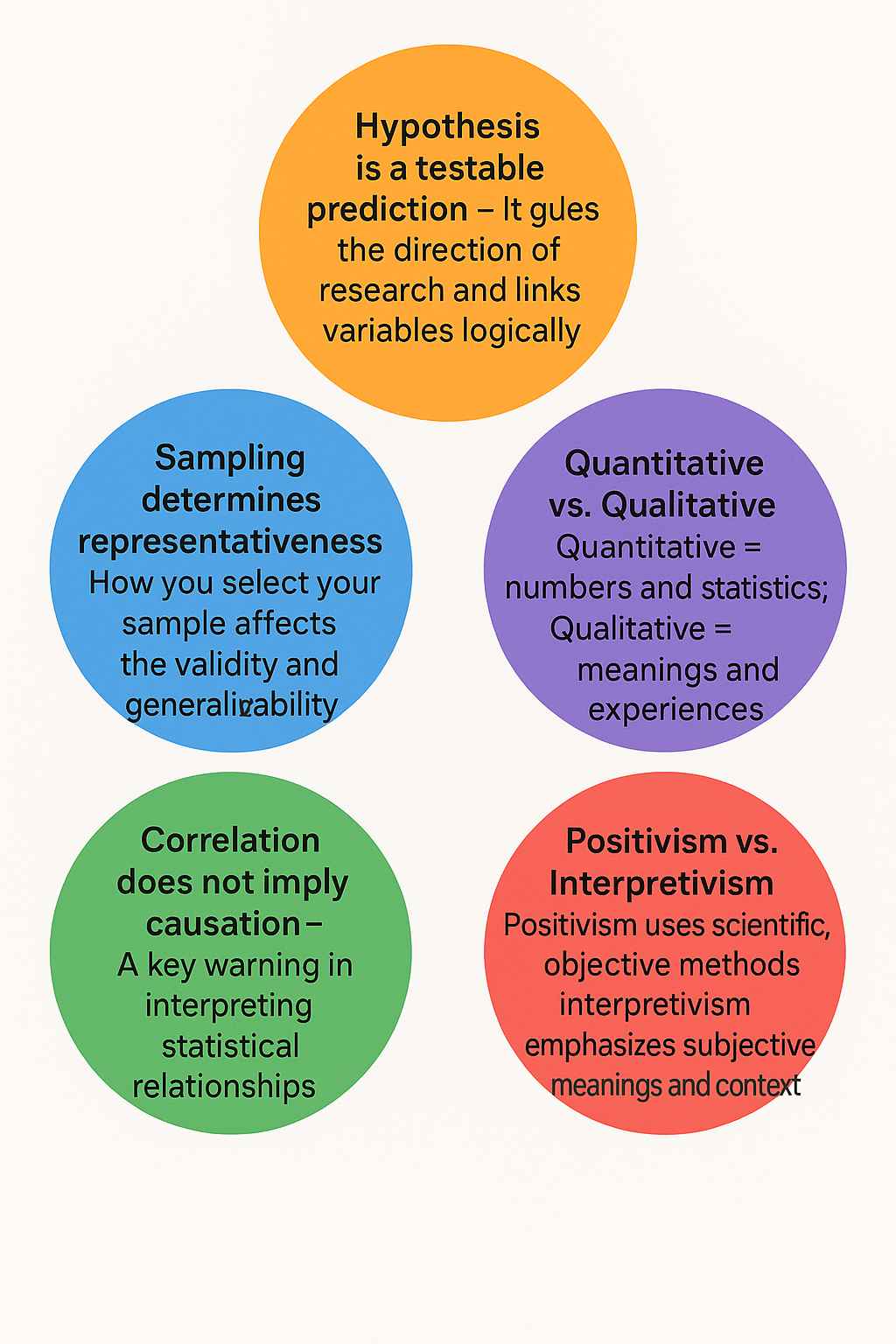

2. Philosophical Foundations: Positivism and Anti-Positivism

The methodological choices in social research are deeply influenced by philosophical

foundations. Two dominant paradigms—positivism and anti-positivism—represent

contrasting epistemological positions that have shaped sociological thinking since the

19th century. Positivism, rooted in the works of Auguste Comte, holds that society

can be studied with the same objectivity and precision as the natural sciences. It relies

on observable, measurable facts and assumes that social reality exists independently

of human consciousness. Positivist researchers emphasize quantification, structured

methods, and statistical analysis. They often use surveys, experiments, or secondary

data to examine causal relationships and test hypotheses. For example, a positivist

might use census data to study the correlation between education and fertility rates

across regions. The underlying assumption here is that patterns in social life can be

discovered, generalized, and even predicted using empirical methods.

In contrast, anti-positivism—or interpretivism—argues that the social world is

fundamentally different from the natural world and must be understood in terms of

meaning, context, and human agency. Thinkers like Max Weber, Wilhelm Dilthey,

and later Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann argued that social reality is

constructed through interaction, symbols, and shared understandings.

Anti-positivist researchers prioritize qualitative methods such as in-depth interviews,

participant observation, ethnography, and life histories. Their goal is to uncover how

individuals interpret their world and construct meanings, rather than merely

measure external behaviors. For example, to understand why farmers commit suicide

in certain regions, interpretivists would explore cultural perceptions of honor,

indebtedness, masculinity, and state failure, rather than simply correlating suicide

rates with rainfall deficits or crop yields.

The positivism versus anti-positivism debate is not just academic—it reflects deeper

questions about what counts as knowledge, how truth is verified, and whose voice

matters. In practice, many sociologists adopt a pragmatic or mixed-method

approach, combining both quantitative and qualitative strategies. Such an approach

allows for a more comprehensive understanding of complex social realities. For

example, a study on urban migration might use surveys to map demographic trends

and ethnographic interviews to explore the lived experiences of migrants. This

methodological pluralism reflects the dynamic and multi-layered nature of society

and acknowledges that no single method can capture the full range of human

experience. As such, the philosophical underpinnings of research continue to guide

not only how data is collected and analyzed but also how social knowledge is framed

and applied.

3. Scientific Method in Sociology

The application of the scientific method in sociology represents an essential

framework through which researchers attempt to produce systematic, replicable, and

verifiable knowledge about society. The scientific method refers to a logical sequence

of steps used to investigate phenomena, test hypotheses, and draw conclusions

grounded in empirical evidence. These steps typically include the formulation of a

research problem, review of literature, hypothesis formulation, data collection,

analysis, and interpretation. While originally developed in the natural sciences, the

scientific method has been successfully adapted by sociologists to study complex

social realities. It provides a structured path that disciplines subjective biases and

ensures that conclusions are based on logical reasoning rather than intuition or

ideology.

In the context of sociology, however, the application of the scientific method must be

adapted to account for the variability and interpretive dimensions of human

behavior. Human subjects are conscious, reflexive, and embedded in social and

cultural contexts, unlike physical objects in natural science experiments. For example,

a study on the voting behavior of urban youth must account for not only

demographic variables but also political socialization, peer influence, media

narratives, and symbolic associations. The sociologist must therefore be cautious

about oversimplication and remain sensitive to multiple layers of meaning. Despite

these challenges, the scientific method offers a valuable roadmap for organizing

inquiry and minimizing bias. It enables researchers to move from anecdotal

observations to structured analysis, from speculation to evidence-based conclusions.

Moreover, the scientific method fosters a culture of critical inquiry. Sociological

research involves the constant questioning of assumptions, the search for patterns,

and the willingness to revise theories in light of new evidence. This critical reflexivity

is what distinguishes scientific sociology from ideology or propaganda. For example,

the scientific investigation of caste-based discrimination must interrogate cultural

norms, institutional practices, and structural inequalities without being clouded by

popular narratives or political motivations. Importantly, the scientific method also

demands replicability and transparency, encouraging researchers to make their

methods and data public for peer review and critique. In this way, sociology as a

discipline aligns itself with the broader values of scientific temper, reason, and ethical

inquiry, while remaining open to the diversity and dynamism of social life.

4. Types of Research: Basic, Applied, Action, and Evaluative

Social research serves multiple objectives, and its classification into different types is

based on the purpose, scope, and expected outcomes of the study. Basic or

fundamental research is primarily concerned with expanding the frontiers of

knowledge. It is theoretical, abstract, and often not tied to immediate practical

concerns. For example, studying the nature of social roles in tribal communities or

exploring theories of social stratification falls under basic research. The aim here is to

contribute to conceptual clarity and theoretical advancement. Though it may not

result in direct policy recommendations, basic research forms the intellectual

backbone of sociology by providing foundational insights into how society works.

Applied research, on the other hand, is more problem-oriented and is conducted

with a view to solving specific social issues. It bridges the gap between theory and

practice by generating actionable knowledge. Examples of applied research include

studies on school dropout patterns, unemployment trends among rural youth, or the

impact of microfinance on women’s empowerment. Such research is often

commissioned by governments, NGOs, or international agencies to guide planning,

policy-making, or program implementation. Applied research demands

methodological rigor as well as practical sensitivity, ensuring that findings are relevant

to the stakeholders involved.

A third category is action research, which represents a collaborative and participatory

approach to research. Developed by scholars like Kurt Lewin, action research seeks to

bring about social change by involving the subjects of the study in the research

process itself. It is commonly used in community development, educational reform,

and participatory governance projects. In action research, researchers act as

facilitators rather than distant observers, working with communities to identify

problems, implement interventions, and evaluate outcomes. This kind of research

blurs the line between academic investigation and activism, making knowledge

production a democratic and empowering process.

Lastly, evaluative research focuses on assessing the effectiveness, efficiency, and

impact of existing programs, policies, or interventions. It uses both qualitative and

quantitative techniques to determine whether a given initiative is meeting its goals

and how it can be improved. For instance, an evaluation of the Pradhan Mantri Awas

Yojana would involve analyzing beneficiary satisfaction, cost-effectiveness, and

improvements in living conditions. Evaluative research is crucial for evidence-based

governance and accountability, helping policy-makers make informed decisions.

These various types of research are not mutually exclusive; rather, they often

complement each other in the larger ecosystem of social inquiry, offering a diverse

toolkit to address the multifaceted challenges of society.

5. Research Design and Hypothesis

A well-structured research design is the blueprint of a sociological investigation. It

lays down the plan for how a study will be conducted—from the selection of

participants and methods of data collection to the techniques of analysis and

interpretation. Research design ensures coherence between research questions,

objectives, theoretical frameworks, and empirical procedures. It anticipates potential

challenges and provides strategies to address them, thereby enhancing the credibility,

validity, and reliability of the study. Broadly, research designs can be classified as

exploratory, descriptive, diagnostic, and experimental. Exploratory design is used

when the researcher aims to investigate new or poorly understood issues, such as the

rise of digital addiction among adolescents. Descriptive design provides a detailed

picture of a phenomenon, like demographic patterns in urban slums. Diagnostic

research seeks to identify causes and solutions to a specific problem, whereas

experimental design—though rare in sociology—involves manipulation of variables

under controlled conditions to observe effects.

An integral part of research design is the formulation of a hypothesis—a tentative

explanation or prediction that can be tested through empirical investigation. A

hypothesis links two or more variables and provides direction to the research. For

example, one may hypothesize that “students from female-headed households

perform better academically due to greater parental attention.” Hypotheses can be

classified as null (stating no relationship between variables), alternative (stating a

positive or negative relationship), directional (indicating the nature of the

relationship), or non-directional (only indicating an association). A good hypothesis

is clear, concise, testable, and grounded in theoretical knowledge. It allows the

researcher to convert abstract questions into measurable inquiries, enhancing the

scientific rigor of the study.

In addition to hypotheses, research design must also address issues of sampling,

validity, and ethical considerations. The choice of sample—its size,

representativeness, and selection method—affects the generalizability of findings.

Validity ensures that the study actually measures what it claims to, while reliability

refers to the consistency of results across time and conditions. Ethical concerns, such

as informed consent, confidentiality, and non-harm to participants, are fundamental

to any research endeavor. In sum, research design is not just a technical step but a

strategic, ethical, and theoretical foundation that determines the overall success and

integrity of the sociological investigation.

6. Methods of Data Collection: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches

Data collection is the cornerstone of social research. The methods employed must be

carefully chosen based on the research objectives, nature of the phenomenon under

study, the philosophical orientation (positivist or interpretivist), and the available

resources. Broadly, data collection methods are divided into quantitative and

qualitative categories, each with its own logic, strengths, and limitations.

Quantitative methods involve the collection of numerical data that can be statistically

analyzed to reveal patterns, correlations, and generalizations. These include surveys,

structured questionnaires, experiments, and content analysis of numeric records.

They are commonly used in large-scale studies that aim for objectivity, reliability, and

replicability. For example, a national survey on youth employment trends using

closed-ended questions can help identify macro-level associations between education

and job attainment.

In contrast, qualitative methods emphasize understanding the depth, complexity,

and contextuality of social experiences. They deal with non-numerical data such as

narratives, observations, images, and meanings. Methods such as in-depth interviews,

focus group discussions, ethnography, and participant observation allow the

researcher to gain insight into the lived experiences and symbolic worlds of

individuals. For instance, a qualitative study on dowry practices in North India

might involve spending time within families, attending ceremonies, and interpreting

how social norms are maintained or challenged. These methods are flexible,

open-ended, and iterative, allowing the researcher to adapt their tools as new insights

emerge in the field.

Rather than viewing these two categories as mutually exclusive, many contemporary

sociologists advocate for a mixed-methods approach, which combines the breadth of

quantitative research with the depth of qualitative inquiry. This methodological

triangulation enhances the robustness of findings and provides a more holistic

understanding of social phenomena. For example, in studying rural-urban migration,

surveys might help map migration patterns, while interviews could explore personal

stories of hardship, aspirations, and adaptation. Regardless of the method used, data

collection must be guided by ethical principles such as informed consent, voluntary

participation, cultural sensitivity, and the protection of vulnerable populations.

Ultimately, the choice of data collection method reflects not only technical efficiency

but also the epistemological and ethical orientation of the researcher.

7. Sampling Techniques: Probability and Non-Probability Sampling

Sampling is the process of selecting a subset of individuals, groups, or units from a

larger population to make inferences about the whole. Since it is often impossible or

impractical to study an entire population, especially in large-scale social research,

sampling allows for manageable, cost-effective, and timely data collection. The two

principal categories of sampling methods are probability sampling and

non-probability sampling, each suitable for different research goals and conditions.

Probability sampling is based on the principle of randomization, where every

member of the population has a known, non-zero chance of being selected. This

method enables generalization of findings to the broader population and is preferred

in quantitative studies that seek statistical rigor. Common types include:

- Simple random sampling, where participants are chosen purely by chance, ensuring equal likelihood of selection.

- Stratied sampling, where the population is divided into subgroups (e.g., caste, gender, income), and random samples are drawn from each to ensure representation.

- Systematic sampling, where every nth individual from a list is selected.

- Cluster sampling, where groups or clusters (like villages or schools) are randomly selected, and data is collected from all or some individuals within them

On the other hand, non-probability sampling does not use random selection and is often employed in qualitative research or when a sampling frame is unavailable. While it limits generalizability, it allows for rich, context-specific insights. Types include:

- Purposive sampling, where individuals are selected based on particular characteristics or experiences relevant to the study

- Snowball sampling, often used in studying hidden or stigmatized populations, where existing participants refer others.

- Convenience sampling, where the researcher selects whoever is readily available, often used in exploratory or pilot studies.

- Quota sampling, where researchers ensure a xed number of participants from specific categories

The choice between these methods depends on the research objectives, resources, and ethical constraints. In large-scale government surveys like NFHS or NSSO, probability sampling is essential for national-level policy planning. In contrast, a feminist ethnography on domestic violence may rely on purposive and snowball methods to reach women willing to share their experiences. Thus, sampling is both a technical and strategic act that shapes the scope, credibility, and implications of sociological research.

8. Scaling and Measurement: Likert, Guttman, and Thurstone Scales

Measurement is the process of assigning values or symbols to social phenomena in a

consistent and reliable manner, enabling comparison and analysis. In sociology,

measurement often deals with abstract concepts or “constructs” such as alienation,

trust, religiosity, or attitude toward gender roles. To quantify such constructs,

researchers use scaling techniques, which transform qualitative judgments into

quantitative scores. The most commonly used scales include the Likert Scale,

Guttman Scale, and Thurstone Scale, each based on different assumptions and

design principles.

The Likert Scale, developed by Rensis Likert, is widely used for measuring attitudes

and opinions. It presents a series of statements related to a particular issue, and

respondents indicate their level of agreement or disagreement on a symmetric scale

(e.g., strongly agree to strongly disagree). Each response is assigned a numerical value,

and the sum or average represents the respondent’s overall attitude. For example, in a

study on gender equality, Likert items might include statements like “Women should

be paid equal to men for the same work.” This method is simple to administer and

analyze, making it popular in surveys and social psychology.

The Guttman Scale is a cumulative or unidimensional scale, where items are arranged

in a hierarchical order of intensity. Agreement with a higher-level statement implies

agreement with all lower-level ones. It is particularly useful when the researcher

wants to measure progressive attitudes. For example, a Guttman scale on political

participation might include items such as: (1) reads political news, (2) discusses

politics, (3) votes regularly, (4) attends rallies, (5) runs for oce. If a person agrees

with item 4, they are assumed to agree with 1 to 3 as well. While conceptually

elegant, constructing a valid Guttman scale requires careful testing of item scalability.

The Thurstone Scale, developed by Louis Thurstone, uses the method of

equal-appearing intervals. Experts rst rate a large set of statements on a particular

attitude from least to most favorable, and then a subset of statements representing

dierent points on the continuum is selected. Respondents are asked to agree or

disagree with these statements, and their attitudes are inferred from the mean scale

value of the agreed statements. Though more complex and time-consuming, the

Thurstone method allows for a nuanced and psychometrically grounded

measurement of attitudes.

These scaling techniques help researchers convert subjective and often ambiguous

social sentiments into structured, analyzable data. However, sociologists must also be

aware of limitations such as response bias, social desirability, and cultural variation in

interpretation. Therefore, scale construction must be rigorous, validated through

pilot testing, and contextually grounded to ensure that the measurements truly

reflect the social reality being studied.

9. Tools of Data Collection: Interview, Questionnaire, Observation, and Schedule

In social research, the tools of data collection serve as the primary instruments

through which researchers gather empirical evidence. These tools vary according to

the nature of the study, the research design, the availability of resources, and the

philosophical orientation of the researcher. The most commonly used tools in

sociological research include interviews, questionnaires, observation, and

schedules—each possessing distinct methodological strengths and weaknesses.

The interview is one of the most flexible and widely used qualitative tools. It involves

a verbal interaction between the researcher and the respondent, aimed at eliciting

information, opinions, experiences, and meanings. Interviews can be classified as

structured, semi-structured, or unstructured. Structured interviews follow a

predetermined set of questions, leaving little room for deviation, and are useful for

large-scale surveys where consistency is crucial. Semi-structured interviews balance

structure with flexibility, allowing the researcher to probe deeper into interesting

responses. Unstructured interviews, often used in ethnographic or life-history

research, are conversational in tone and allow respondents to narrate their

experiences in their own words. Interviews are particularly useful for exploring

sensitive topics like caste discrimination, domestic violence, or sexuality, where trust,

empathy, and rapport-building become crucial.

The questionnaire is a structured instrument consisting of a series of questions or

statements to which respondents provide answers. It is typically self-administered

and can be distributed in person, by post, or digitally. Questionnaires are efficient for

collecting data from a large population and are widely used in quantitative research.

They can include both closed-ended questions, which oer xed response options,

and open-ended questions, which allow for elaboration. However, questionnaires

have limitations: they often suer from low response rates, and there is little

opportunity to clarify doubts or probe deeper. The wording and sequencing of

questions also influence the quality of responses, necessitating careful design and

pilot testing.

Observation involves systematically watching and recording behaviors, events, or

interactions in their natural setting. It is particularly valuable in studies of group

dynamics, rituals, non-verbal communication, and public behavior. Observation can

be participant or non-participant, and overt or covert. In participant observation, the

researcher becomes part of the group being studied, while in non-participant

observation, they remain a detached observer. For example, a study on religious

festivals may involve the researcher taking part in rituals and understanding their

symbolic meaning from within the community. The strength of observation lies in

its ability to capture real-time behavior and contextual nuances that may be missed in

interviews or surveys. However, it also raises ethical issues—especially in covert

observation—and demands high levels of skill, reflexivity, and endurance from the

researcher.

The schedule is similar to a questionnaire but is administered by the researcher or an

investigator, rather than being filled out by the respondent independently. It is

commonly used in census surveys and large-scale government data collection

exercises. Since the researcher records the responses, this tool ensures higher accuracy,

especially when dealing with illiterate or semi-literate respondents. Schedules can also

ensure clarity, prevent misinterpretation, and enhance response rates. However, they

require trained investigators and are time- and cost-intensive.

In sum, the selection of tools is a critical methodological decision that influences the

reliability, validity, and depth of data collected. Each tool must be suited to the

research problem, and in many studies, a combination of tools is used to triangulate

data and capture the multidimensional nature of social phenomena.

10. Data Processing and Classification

Once data is collected, it must be processed and prepared for analysis. This stage,

though often overlooked, is crucial for ensuring that the findings are systematic,

transparent, and interpretable. Data processing involves several sequential steps:

editing, coding, classification, and tabulation.

Editing is the rst step and refers to checking the collected data for completeness,

consistency, and accuracy. In the case of interviews or eld notes, this may involve

clarifying unclear responses or verifying transcriptions. In survey-based studies,

missing entries, illegible handwriting, or contradictory answers must be corrected or

noted. Editing ensures that only high-quality, usable data enters the analysis stage.

Coding involves assigning numerical or symbolic codes to responses so that they can

be organized systematically. In quantitative research, this often means converting

responses into digits for statistical processing. For instance, gender might be coded as

1 for male and 2 for female, or levels of agreement in a Likert scale might range from

1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Open-ended responses can be thematically

analyzed and then coded into categories. The process of coding must be both

exhaustive and mutually exclusive to maintain clarity and precision.

Classification is the logical arrangement of data into categories or groups based on

shared characteristics. This process simplifies the complexity of raw data, making

patterns easier to detect. Classification may be chronological (time-based),

geographical (region-based), qualitative (based on attributes like caste, religion,

occupation), or quantitative (based on numeric values). For example, responses in a

study on marital satisfaction could be classified into categories like high, moderate,

and low satisfaction, or grouped by age, income, and education.

Tabulation refers to presenting data in tabular form for easy comprehension and

analysis. Tables organize raw numbers or coded categories into rows and columns,

allowing researchers to see frequencies, percentages, and cross-tabulations. They

form the basis for further statistical computation and graphical representation. In

modern research, tools like Excel, SPSS, R, or STATA are used to automate data

processing and tabulation, significantly reducing human error and increasing

efficiency.

Thus, data processing and classification bridge the gap between raw, unstructured

data and meaningful, actionable insights. It is a technical but indispensable part of

research that ensures order, reliability, and analytic clarity.

11. Measures of Central Tendency and Dispersion

In quantitative research, summarizing and interpreting numerical data is essential to

uncover patterns and test hypotheses. Descriptive statistics are used to condense data

sets into meaningful summaries, with two fundamental categories being measures of

central tendency and measures of dispersion.

The measures of central tendency indicate the center or average of a data distribution

and help identify a typical value that represents the data set. There are three primary

measures: mean, median, and mode.

- The mean is the arithmetic average and is calculated by summing all values and dividing by the total number of observations. It is sensitive to extreme values (outliers), which can distort the interpretation in skewed distributions.

- The median is the middle value when the data is arranged in order. It is particularly useful in distributions with outliers or non-normal shapes. For instance, median household income is often more representative than mean in a society with stark income inequality.

- The mode is the value that occurs most frequently in the data set. It is especially useful for categorical data (like religion or language) and helps identify dominant characteristics in a population.

While central tendency provides an estimate of average behavior, measures of dispersion capture the variability or spread of data. They indicate how much individual observations deviate from the average.

- The range is the difference between the highest and lowest values. Though simple to compute, it is highly affected by outliers.

- Variance measures the average squared deviation from the mean, offering insight into the spread of data points.

- Standard deviation, the square root of variance, is a more interpretable metric as it uses the same units as the original data. A low standard deviation indicates that the data points are clustered around the mean, while a high standard deviation implies wide variability.

These statistical tools are not merely mathematical exercises; they have significant

sociological relevance. For example, in assessing educational inequality, the average

scores (mean) may be similar across regions, but the standard deviation can reveal

disparities within classrooms or across social groups. Similarly, when comparing

family size in urban vs. rural areas, the median may oer a better summary than the

mean, given the influence of demographic outliers.

Hence, central tendency and dispersion work together to provide a comprehensive

picture of the data landscape, allowing researchers to describe, interpret, and

communicate fidings with clarity and precision.

12. Correlation and Regression: Understanding Relationships Between Variables

In the realm of statistical analysis, correlation and regression are powerful tools that

help sociologists understand the relationships between two or more variables. These

methods go beyond mere description, providing insights into how changes in one

variable relate to changes in another. Their value in sociological research is immense,

particularly when trying to test causal models, identify patterns of inequality, or

assess social trends.

Correlation measures the strength and direction of the association between two

variables. The most commonly used statistical tool for this purpose is Pearson’s

correlation coefficient (r), which ranges from –1 to +1. A value close to +1 indicates

a strong positive relationship (as one variable increases, the other increases), while a

value close to –1 signifies a strong negative relationship (as one variable increases, the

other decreases). A value around 0 suggests little or no linear relationship. For

example, in a study on education and income, a high positive correlation would

indicate that higher levels of education are associated with higher income levels.

However, it’s critical to remember that correlation does not imply causation—a third

factor could be influencing both variables.

In contrast, regression analysis goes a step further by not only identifying

relationships but also modeling them. The most basic form is simple linear

regression, where one independent variable (X) is used to predict the value of a

dependent variable (Y). The relationship is expressed through a regression equation:

Y = a + bX + e,

where a is the intercept, b is the slope (regression coefficient), and e is the error term.

The coefficient b indicates how much Y changes with a one-unit change in X. This

method is useful in forecasting, policy planning, and hypothesis testing. For example,

a regression model may be used to predict literacy rates based on per capita

government expenditure on education.

Multiple regression involves two or more independent variables, allowing researchers

to isolate the effect of each while controlling for others. This is particularly valuable

in sociology, where social phenomena are influenced by a web of interrelated factors.

A study on child nutrition, for instance, may include variables such as maternal

education, household income, caste, and access to health services. Regression thus

enables a nuanced understanding of causality, adjusting for potential confounders.

The validity of correlation and regression results depends on several assumptions,

including linearity, normal distribution of errors, and homoscedasticity. Violations

of these assumptions can lead to incorrect conclusions. Furthermore, both

techniques are limited to linear relationships, and complex social dynamics often

require non-linear models or qualitative insights. Nevertheless, correlation and

regression remain foundational tools in empirical sociology, helping researchers

translate abstract theories into empirically testable models.

13. Tests of Significance: Hypothesis Testing in Social Research

While descriptive statistics summarize data, inferential statistics allow researchers to

make generalizations from a sample to the larger population. This is where tests of

significance come into play. They help determine whether the patterns observed in

the data are statistically meaningful or could have occurred by random chance. The

basic logic involves setting up a null hypothesis (H₀)—which assumes no relationship

or effect—and an alternative hypothesis (H₁)—which posits the presence of a

relationship or effect. Statistical tests are then used to evaluate whether there is

sufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis.

One of the most widely used tests is the t-test, which compares the means of two

groups to determine if they are significantly different from each other. For example, a

t-test can be used to assess whether urban and rural students differ in academic

performance. The result is expressed in terms of a p-value—if the p-value is less than

a chosen significance level (usually 0.05), the null hypothesis is rejected, and the

difference is deemed statistically significant.

The Chi-square (χ

²) test is another important non-parametric test used to examine

the association between categorical variables. It compares the observed frequency

distribution with the expected distribution under the null hypothesis. This test is

particularly useful in sociology for analyzing cross-tabulated data such as caste and

occupation, education and voting behavior, or gender and media preference. For

instance, a Chi-square test may reveal whether there is a statistically significant

association between caste background and access to government jobs.

Other significance tests include the ANOVA (Analysis of Variance), used when

comparing means across more than two groups, and Z-tests, useful when the sample

size is large and standard deviation is known. F-tests are used in regression analysis to

assess the overall significance of the model. Each of these tests comes with its own set

of assumptions and limitations, and selecting the appropriate test requires a clear

understanding of the data, the research question, and the level of measurement of the

variables involved.

significance testing helps maintain scientific rigor and objectivity. However, it should

not be the sole criterion for judging the value of research. A statistically significant

result may be substantively trivial, and an insignificant result may have theoretical or

policy relevance. Sociologists must therefore combine statistical findings with

theoretical interpretation, ethical awareness, and critical reflexivity to generate

meaningful knowledge.

14. Report Writing and Ethics in Social Research

The nal stage of the research process is the communication of findings through

report writing, which serves as both a documentation and dissemination tool. A

well-written research report reflects clarity of thought, methodological rigor, and

analytical depth. It allows peers, policy-makers, and the public to evaluate the study,

replicate the methodology, and apply the insights to practical or theoretical concerns.

A good research report typically includes the following components: introduction,

statement of the problem, review of literature, methodology, data analysis, findings,

conclusions, recommendations, and references.

The introduction lays out the research problem, its significance, and objectives. The

literature review contextualizes the study within existing scholarship, identifying gaps

the current research aims to ll. The methodology section explains the research

design, tools of data collection, sampling strategy, and analytical techniques used.

This section must be detailed enough to ensure transparency and reproducibility.

The analysis and findings present the core empirical results, supported by tables,

graphs, or qualitative excerpts. This is followed by a discussion, which links findings

to theoretical frameworks and broader implications. Finally, conclusions and policy

recommendations synthesize the insights and suggest ways forward.

Equally important are ethics in research, which govern the moral obligations of

researchers toward participants, society, and the discipline. Key ethical principles

include informed consent, where participants voluntarily agree to take part after

being made aware of the study’s purpose and procedures; confidentiality, where

personal data is protected from unauthorized access; and non-maleficence, where the

researcher ensures no physical, emotional, or reputational harm comes to

participants. These concerns are especially acute in vulnerable

populations—children, survivors of violence, or those under surveillance.

With the rise of digital technologies, new ethical dilemmas have emerged, such as

data scraping, digital consent, AI-based profiling, and algorithmic bias. Researchers

working with social media data, for example, must decide whether publicly available

posts can be ethically analyzed without consent. Institutional Ethics Committees

(IECs) now play a crucial role in reviewing research proposals to ensure compliance

with ethical standards. Moreover, the research report must acknowledge limitations,

disclose conflicts of interest, and give credit through proper citation to maintain

intellectual integrity.

Thus, report writing is not merely a formal requirement but the culmination of the

entire research process. It bridges the gap between empirical findings and societal

application, while ethics ensures that the production of knowledge is just, respectful,

and socially responsible.

15. Contemporary Issues in Research: Big Data, Artificial Intelligence, and Digital Sociology

In the 21st century, social research is undergoing a radical transformation driven by

technological advancements, especially in the areas of Big Data, Artificial Intelligence

(AI), and Digital Sociology. These developments are not just innovations in method,

but shifts in the very epistemology of research—reshaping how knowledge is created,

validated, and used.

Big Data refers to extremely large and complex datasets that cannot be processed

using traditional statistical tools. This data is often generated through digital

interactions such as social media posts, mobile phone usage, online transactions,

satellite imagery, and sensor networks. For sociologists, Big Data opens new avenues

to study behavior in real-time and at scale. For instance, analyzing Twitter

conversations during elections can provide insights into public sentiment,

polarization, and the spread of misinformation. Similarly, mobile phone data can

track internal migration, urban mobility, or health behavior during pandemics.

However, Big Data also raises serious concerns about data privacy, consent,

surveillance, and digital divide—as marginalized communities may be either

over-surveilled or completely absent in such datasets.

Artificial Intelligence (AI), especially machine learning and natural language

processing, is increasingly being used to analyze unstructured data—such as text,

images, or videos—at unprecedented speed and accuracy. AI tools can now classify

documents, detect sentiments, and even predict behaviors based on complex

patterns. For example, algorithms can be trained to identify patterns of hate speech,

cyber bullying, or online radicalization. AI can also assist in automating coding,

pattern recognition, and statistical modeling. However, AI-based methods are not

neutral—they carry the biases of their creators and datasets. Predictive models used

in policing or hiring may replicate existing social inequalities if not critically audited.

Hence, the rise of AI demands a reflexive sociology that interrogates the politics of

algorithms, the opacity of machine decisions, and the dehumanization of social

processes.

Digital Sociology has emerged as a subfield that explicitly focuses on how digital

technologies are shaping society and how sociologists should study this

transformation. It includes the sociological study of the internet, digital labor,

platform capitalism, virtual communities, and datafication of everyday life.

Traditional research tools like interviews or observations are now being augmented

with digital ethnography, social network analysis, and text mining. For example,

platforms like Reddit, Facebook, or Instagram oer sociologists a wealth of data on

identity construction, social movements, or consumer behavior—but also demand

new ethical frameworks to handle this data responsibly.

India offers a unique terrain for digital research. With over 800 million internet users

and growing digital literacy, social scientists can explore rural digitization, fintech

inclusion (like UPI and Aadhaar), online education, and digital caste politics. Yet, the

digital divide persists—marginalized castes, tribal groups, and women in rural areas

remain underrepresented or invisible in digital data. Thus, while technology expands

the scope of social research, it also reinforces old exclusions in new forms.

In conclusion, the contemporary research landscape is marked by exciting

possibilities and ethical complexities. The challenge for sociologists is to embrace

these new tools without losing the critical, humanistic, and context-sensitive ethos of

the discipline. The digital age does not eliminate the need for fieldwork, narrative

depth, or ethical reflexivity—it simply expands the toolkit and the terrains of inquiry

16. Conclusion

Social research today stands at a critical crossroads—facing both expansive

opportunities and significant challenges. On one hand, there is a growing recognition

of evidence-based policy, interdisciplinary collaboration, and technological

innovation. On the other, the eld is confronting threats to academic freedom,

increasing commercial influence, and ethical dilemmas posed by data capitalism. In

this rapidly shifting terrain, the future of sociological research will depend on its

ability to remain methodologically rigorous, ethically grounded, and socially

relevant.

In India, social research must play a pivotal role in addressing the pressing issues of

inequality, communalism, environmental crisis, gender discrimination, and digital

transformation. Large-scale programs like NITI Aayog’s policy evaluation, the

National Education Policy (NEP), Swachh Bharat Abhiyan, or digital governance

through Aadhaar provide both opportunities and responsibilities for researchers.

Sociologists need to not only collect and analyze data but also question whose voices

are included, which paradigms dominate, and what structural inequalities are being

obscured or normalized. Research must move from extractive models to

participatory, decolonial, and community-led frameworks that empower those being

studied.

Methodologically, we are moving toward greater integration of quantitative and

qualitative tools. Statistical rigor must be complemented with interpretive sensitivity.

Tools like GIS mapping, digital storytelling, ethnographic filmmaking, and predictive

modeling must be integrated with classical techniques like observation, historical

analysis, and narrative interviewing. The training of future researchers should reflect

this pluralism—emphasizing not just technical skills but also critical thinking,

cultural competence, and ethical literacy.

Another significant development is the globalization of research—with increasing

collaboration across countries, institutions, and disciplines. Yet, this also risks

marginalizing indigenous knowledge systems, non-English scholarship, and local

epistemologies. Indian sociology must assert its own priorities—rooted in its unique

social reality, historical trajectory, and intellectual traditions. Scholars like M.N.

Srinivas, G.S. Ghurye, Yogendra Singh, and Veena Das have shown that

theory-building in India need not merely replicate Western paradigms but can be

contextually grounded and globally significant.

Finally, statistics in sociology should not be seen as mere number-crunching but as a

way of telling human stories—about inequality, resistance, suffering, and change.

Measures like standard deviation or regression coefficients become meaningful only

when interpreted within a socio-historical context. Numbers must not obscure lived

realities, but illuminate them.

References

- Babbie, E. R. (2013). The Practice of Social Research. Cengage Learning.

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social Research Methods. Oxford University Press.

- Goode, W.J. & Hatt, P.K. (1952). Methods in Social Research. McGraw-Hill.

- Neuman, W. L. (2014). Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Pearson.

- Gupta, S. C. & Kapoor, V. K. (2021). Fundamentals of Mathematical Statistics. Sultan Chand & Sons.

- Krishnaswamy, O. R. (2008). Methodology of Research in Social Sciences. Himalaya Publishing House.

- IGNOU Study Material, Block-1. (Uploaded by User).

- Creswell, J. W. & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Sage.

We are proud to present you this section on Research Method And Statistics. We hope this section on Research Method And Statistics will be as useful to you as it is meant to be.

|

|

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|