Home >> Basic Concepts >> Social Institutions

Social Institutions

Index

- Introduction to Social Institutions

- Nature and Characteristics of Social Institutions

- Functions of Social Institutions

- Types of Social Institutions

- Theoretical Perspectives on Social Institutions

- Evolution and Transformation of Social Institutions

- Social Institutions in the Indian Context

- Role of Institutions in Social Control and Social Change

- Criticisms and Contemporary Challenges to Social Institutions

- Conclusion

Introduction to Social Institutions

Social institutions are the fundamental building blocks of society. They refer to organized patterns of beliefs and behavior centered around basic social needs. Sociologically, institutions are enduring systems of established and embedded social rules that structure social interactions. Institutions operate at both micro and macro levels, encompassing everything from daily routines within families to large-scale bureaucratic systems in governments. Auguste Comte, the father of sociology, envisioned society as a complex system with various parts working together, and institutions are central to this organic whole. They create norms, maintain order, reproduce culture, and provide a framework for the behavior of individuals within a society. Without institutions, society would descend into chaos, as individuals would lack structured guidance. Institutions also act as repositories of collective memory and tradition, sustaining the continuity of cultural practices across generations.

Nature and Characteristics of Social Institutions

Social institutions are characterized by their systematic nature, stability, and normativity. They are more than just groups or organizations; they are social mechanisms that endure over time and have structured roles and rules. One essential characteristic is their normative function: institutions regulate behavior by setting societal expectations. For instance, educational institutions shape expectations around knowledge acquisition and intellectual development. Institutions are also characterized by their functional interdependence. The family as an institution, for example, supports the educational system by socializing children before formal schooling begins. Another crucial feature is their symbolic and cultural dimension. Institutions often represent broader values—religion symbolizes moral values, while legal institutions signify justice. Additionally, institutions tend to be hierarchical and structured, with clearly defined roles and statuses. Over time, they become routinized and taken for granted, which Berger and Luckmann described as “institutionalization” in The Social Construction of Reality. This process involves habitualization of practices, which are eventually legitimized and passed down across generations, gaining objectivity in the social world.

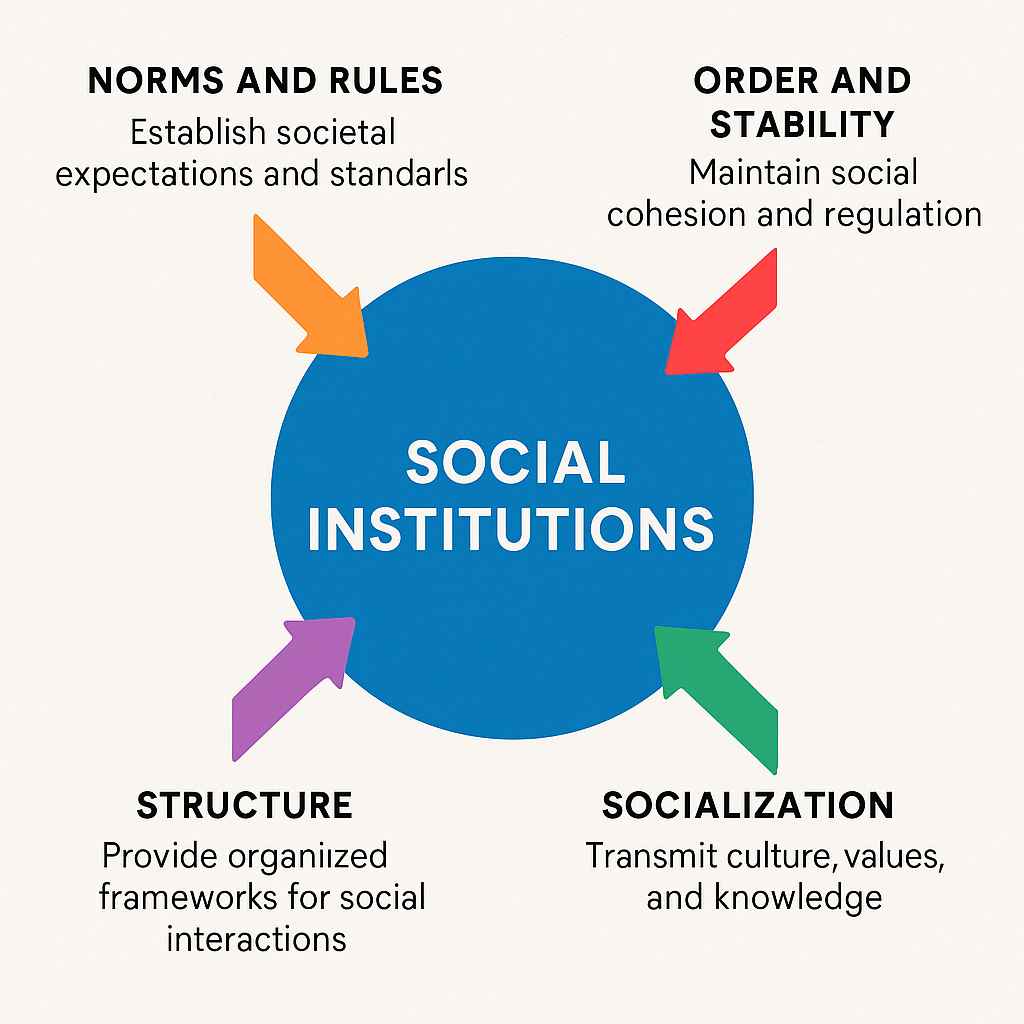

Functions of Social Institutions

Social institutions perform several crucial functions that ensure the smooth functioning of society. Firstly, they fulfill basic human needs—such as reproduction, education, governance, and economic sustenance. The family provides emotional support, nurturance, and the primary environment for early socialization. Education instills knowledge, skills, and cultural values. Political institutions manage power and resource distribution, while the economy handles production and exchange. Secondly, institutions maintain social order and stability. Through norms and sanctions, they regulate individual behavior and discourage deviance. Durkheim emphasized the role of institutions in maintaining social solidarity by promoting shared norms and collective consciousness. Thirdly, institutions facilitate social integration by connecting individuals to broader societal structures. For example, religious institutions bind people through shared beliefs and rituals, creating a sense of belonging. Institutions also ensure the transmission of culture and values, allowing societies to reproduce themselves over generations. They mediate between the individual and the collective, ensuring both personal development and social cohesion.

Types of Social Institutions

Family

The family is often regarded as the most fundamental social institution. It is the primary unit of socialization and plays a crucial role in the emotional, cognitive, and moral development of individuals. It governs reproduction, child-rearing, and inheritance systems. Sociologists have identified various forms of families—nuclear, joint, extended, matrilineal, and patrilineal—each shaped by cultural and economic factors. Functionalists like Parsons have seen the nuclear family as best suited for modern industrial society, performing the vital functions of socialization and stabilization of adult personalities. On the other hand, feminist scholars have critiqued the patriarchal structure of families that perpetuate gender inequality.

Religion

Religion, as an institution, provides moral guidance, emotional solace, and a worldview that shapes human behavior. Emile Durkheim viewed religion as a means of reinforcing social solidarity, identifying it as a set of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things. Marx, however, viewed religion as an ideology used by the ruling class to maintain dominance, calling it the “opiate of the masses.” Weber emphasized the role of religion in driving social change, as seen in his analysis of Protestant ethics and capitalism. Religion influences law, politics, and education, and plays a central role in cultural identity, especially in societies like India where religion and daily life are deeply intertwined.

Education

Education is both a formal and informal institution responsible for the systematic transmission of knowledge, values, and skills. It prepares individuals for social roles and participation in economic and political life. Functionalist theorists view education as a means of role allocation and social integration, while conflict theorists argue that it reproduces social inequalities. Pierre Bourdieu introduced the concept of cultural capital to explain how education perpetuates class hierarchies. Education is also a site of resistance and reform, where marginalized groups demand access and inclusion. In contemporary times, digital education and online learning platforms have significantly transformed the institution of education.

Economy

The Economic institution governs the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. It includes formal sectors like corporations, markets, and labor unions, and informal sectors such as household labor and small-scale trade. Max Weber highlighted the role of rationalization and bureaucracy in the development of modern capitalism. Karl Marx analyzed the economy as the base structure of society that shapes all other institutions through class relations. The economic system—capitalist, socialist, or mixed—shapes people’s life chances and access to resources. Globalization, neoliberalism, and digital finance have altered traditional economic institutions, leading to new forms of labor like gig work, platform economy, and remote freelancing.

Political Institution

Political institutions are structures of governance that exercise authority, create laws, and manage public affairs. These include the state, government, political parties, judiciary, and bureaucracies. The state, as theorized by Max Weber, holds a monopoly over the legitimate use of physical force. Functionalists argue that political institutions maintain order and manage conflicts, while conflict theorists view them as tools of domination. Gramsci’s concept of hegemony explains how the ruling class maintains power through ideological control, not just force. In democratic societies, political institutions also provide platforms for citizen participation, accountability, and representation, though the effectiveness of these ideals varies widely.

Law and Legal System

Law is a formal institution that enforces societal norms through codified rules and regulations. It plays a central role in maintaining order, resolving disputes, and protecting rights. Legal institutions include courts, police, and correctional facilities. The legal system reflects the power dynamics within society—what is criminalized, who is policed, and how justice is delivered often mirror social inequalities. Critical legal studies challenge the neutrality of law, arguing that legal norms are often biased in favor of dominant groups. The Indian legal system, with its blend of colonial legacy and constitutional values, demonstrates the complexity and evolving nature of this institution.

Theoretical Perspectives on Social Institutions

Structural Functionalism

This perspective views social institutions as vital organs of society, each contributing to its stability and survival. Durkheim, Parsons, and Merton emphasized how institutions perform manifest and latent functions. For example, schools explicitly teach subjects (manifest function) but also socialize students into norms like punctuality and obedience (latent function). Institutions are seen as interdependent and collectively contribute to social equilibrium. Changes in one institution affect others, necessitating adaptive responses.

Conflict Theory

Conflict theorists like Karl Marx, C. Wright Mills, and Althusser argue that institutions serve the interests of dominant groups. Institutions are not neutral but perpetuate inequality, often under the guise of merit, order, or tradition. For instance, education is viewed as an ideological apparatus that reproduces class-based advantages. Law and politics are tools of coercion, not consensus. This approach brings attention to power dynamics, domination, and resistance within and across institutions.

Symbolic Interactionism

This micro-sociological perspective focuses on the meanings and interpretations individuals assign to institutions. Social institutions are not just external structures but are enacted and re-enacted in daily interactions. Erving Goffman’s dramaturgical approach helps us understand how roles within institutions are performed in front of audiences—be it the teacher-student dynamic or the doctor-patient relationship. Through social interactions, institutions are continually negotiated and reproduced.

Feminist Perspective

Feminist theorists analyze how institutions are gendered and how they reinforce patriarchal norms. For example, the family is seen as a site of unpaid labor for women, while the legal and political institutions have historically marginalized female voices. Feminists like Sylvia Walby have discussed how institutions intersect to maintain gender hierarchies. Intersectional feminism adds further nuance by analyzing how race, caste, and class interact with gender within institutional frameworks.

Evolution and Transformation of Social Institutions

Social institutions are dynamic and evolve over time in response to economic, technological, cultural, and political changes. For instance, the traditional joint family has been increasingly replaced by nuclear families in urban India due to industrialization and mobility. Education has expanded from gurukuls to digital classrooms, adapting to new pedagogical tools. Similarly, religious practices have changed with modernization and secularization. Political institutions have become more democratized in some areas, while authoritarianism has resurged in others. The digital age has redefined institutions—telemedicine in health, online banking in economy, and virtual parliaments in politics. Despite resistance to change, institutions must adapt to remain relevant.

Social Institutions in the Indian Context

India’s social institutions are deeply embedded in its historical, cultural, and religious fabric. The caste system, though constitutionally abolished, continues to shape access to education, occupation, and marriage. The institution of family remains strong, but increasing divorce rates, delayed marriages, and queer relationships signal transformations. Educational institutions grapple with issues of access, especially for Dalits and minorities. Religion continues to be a powerful force in public life, influencing electoral politics and social cohesion. Indian political institutions, while based on democratic principles, often face challenges like corruption, populism, and majoritarianism. Legal institutions have played a crucial role in advancing rights through PILs and judicial activism but face criticism for delays and inaccessibility

Role of Institutions in Social Control and Social Change

Institutions enforce social norms and thus play a central role in maintaining social control. Schools, religions, and legal systems regulate behavior through internalization, rewards, and punishments. At the same time, institutions are agents of social change. For example, legal reforms such as the abolition of Section 377 or introduction of the Right to Education Act have transformed social realities. Educational institutions can challenge casteist and patriarchal ideologies. Religious institutions can reform practices like untouchability or promote communal harmony. Institutions thus contain both conservative and transformative potential.

Criticisms and Contemporary Challenges to Social Institutions

Institutions face increasing criticism for being rigid, exclusionary, and slow to adapt. Bureaucratic red tape hampers efficiency in political and economic institutions. Gender bias, caste discrimination, and corruption challenge their legitimacy. The digital divide raises concerns about educational equality. Privatization and commodification threaten the core values of institutions like health and education. Many institutions have lost public trust due to repeated failures to deliver justice, transparency, or equity. There is also a crisis of authority—youth increasingly question the legitimacy of religious and political figures. In the 21st century, institutions must undergo structural reforms to remain accountable, inclusive, and relevant.

Conclusion

Social institutions are indispensable to the functioning of society. They provide structure, regulate behavior, reproduce culture, and facilitate continuity and change. However, they are not static; they evolve in response to internal contradictions and external pressures. While institutions maintain order, they can also be sites of conflict and transformation. Understanding institutions through multiple sociological perspectives allows us to critically engage with their functions and failures. In a complex, rapidly changing world, institutions must balance tradition with innovation, order with justice, and continuity with reform. As active members of society, we must engage with institutions not just as passive beneficiaries but as agents of change.

References

- Giddens, A. (2006). Sociology. Polity Press.

- Parsons, T. (1951). The Social System. Free Press.

- Durkheim, E. (1912). The Elementary Forms of Religious Life.

- Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge University Press

A social institution is a complex, integrated set of social norms organized around the preservation of a basic societal value. Obviously, the sociologist does not define institutions in the same way, as does the person on the street. Laypersons are likely to use the term "institution" very loosely, for churches, hospitals, jails, and many other things as institutions. According to Sumner and Keller institution is a vital interest or activity that is surrounded by a cluster of mores and folkways. Sumner conceived of the institution not only of the concept, idea or interest but of a institution as well. By structure he meant an apparatus or a group of functionaries. Lester F Ward regarded an institution as the means for the control and utilization of the social energy.L.T Hobhouse describe institution as the whole or any part of the established and recognized apparatus of social life. Robert Maclver regarded institution as established forms or conditions of procedure characteristic of group activity.

Sociologists agree that institutions arise and persist because of a definite felt need of the members of the society. While there is essential agreement on the general origin of institutions, sociologists have differed about the specific motivating factors. Sumner and Keller maintained that institutions come into existence to satisfy vital interests of man. Ward believed that they arise because of social demand or social necessity. Lewis H Morgan ascribed the basis of every institution to what he called a perpetual want.

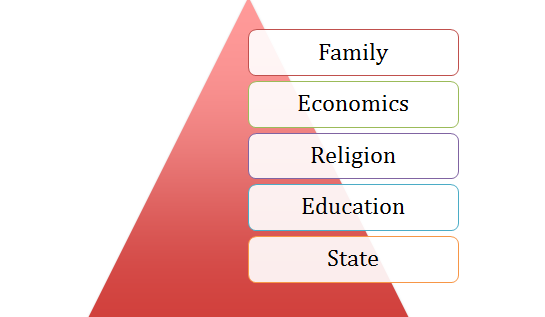

Primary Instituitions

Sociologists often reserve the term "institution" to describe normative systems that operate in five basic areas of life, which may be designated as the primary institutions.

(1) In determining Kinship;

(2) in providing for the legitimate use of power;

(3) in regulating the distribution of goods and services;

(4) in transmitting knowledge from one generation to the next; and

(5) in regulating our relation to the supernatural.

In shorthand form, or as concepts, these five basic institutions are called the family, government, economy, education and religion.

The five primary institutions are found among all human groups. They are not always as highly elaborated or as distinct from one another but in rudimentary form at last, they exist everywhere. Their universality indicates that they are deeply rooted in human nature and that they are essential in the development and maintenance of orders.

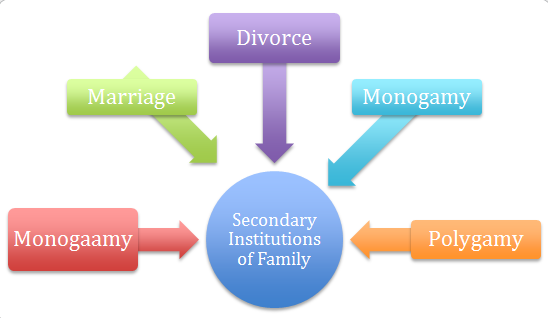

The secondary institutions derived from Family would be

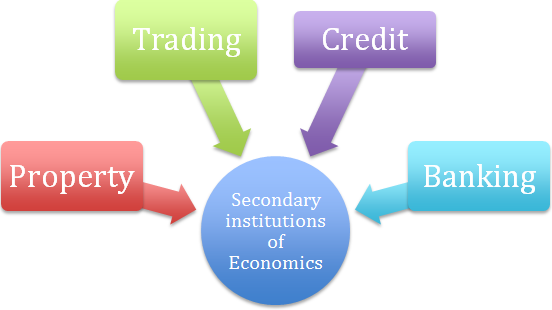

The secondary institutions of economics would be

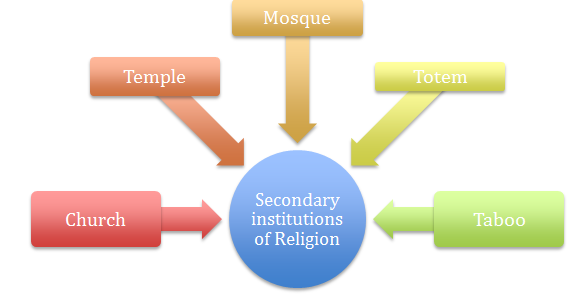

The secondary institutions of Religion would be

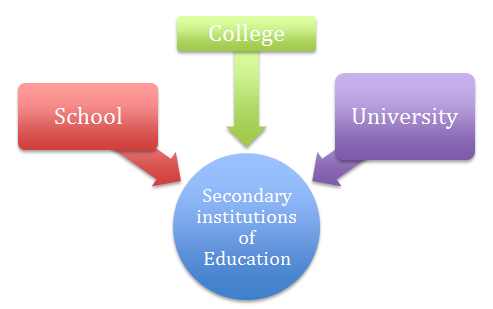

The secondary institutions of education would be

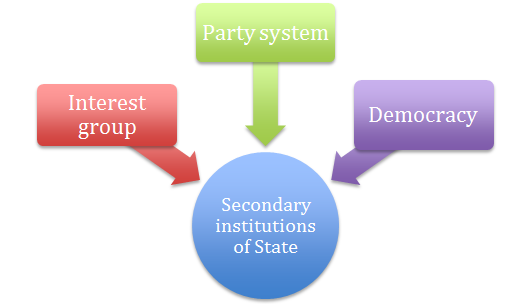

The secondary institutions of State would be

Sociologists operating in terms of the functionalist model society have provided the clearest explanation of the functions served by social institutions. Apparently there are certain minimum tasks that must be performed in all human groups. Unless these tasks are performed adequately, the group will cease to exist. An analogy may help to make the point. We might hypothesize that cost accounting department is essential to the operation of a large corporation. A company might procure a superior product and distribute it then at the price that is assigned to it; the company will soon go out of business. Perhaps the only way to avoid this is to have a careful accounting of the cost of each step in the production and distribution process.

An important feature that we find in the growth of institutions is the extension of the power of the state over the other four primary institutions. The state now exercises more authority by laws and regulations. The state has taken over the traditional functions of the family like making laws regulating marriage, divorce, adoption and inheritance. The authority of state has similarly been extended to economics, to education and to religion. New institutional norms may replace the old norms but the institution goes on. The modern family has replaced the norms of patriarchal family yet the family as an institution continues. Sumner and Keller has classified institutions in nine major categories .He referred to them as pivotal institutional fields and classified them as follows:

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|