Home >> Basic Concepts >> Political Sociology

Political Sociology

Index

- Introduction

- The Origins and Evolution of Political Sociology

- Classical Theories of Power and Authority

- The State: Definitions, Functions, and Debates

- Power Beyond the State: Civil Society and Social Movements

- Political Ideologies and Belief Systems

- Democracy and Political Participation

- Political Elites and Leadership

- Class, Capital, and Political Inequality

- Gender and Politics

- Race, Ethnicity, and Political Identity

- Globalization and Political Transformations

- Nationalism and the Politics of Identity

- Political Violence, War, and Conflict

- Media, Communication, and Political Discourse

- Religion and Politics

- The Rise of Populism and Authoritarianism

- Comparative Political Systems

- Political Sociology in the 21st Century

- Conclusion

Introduction

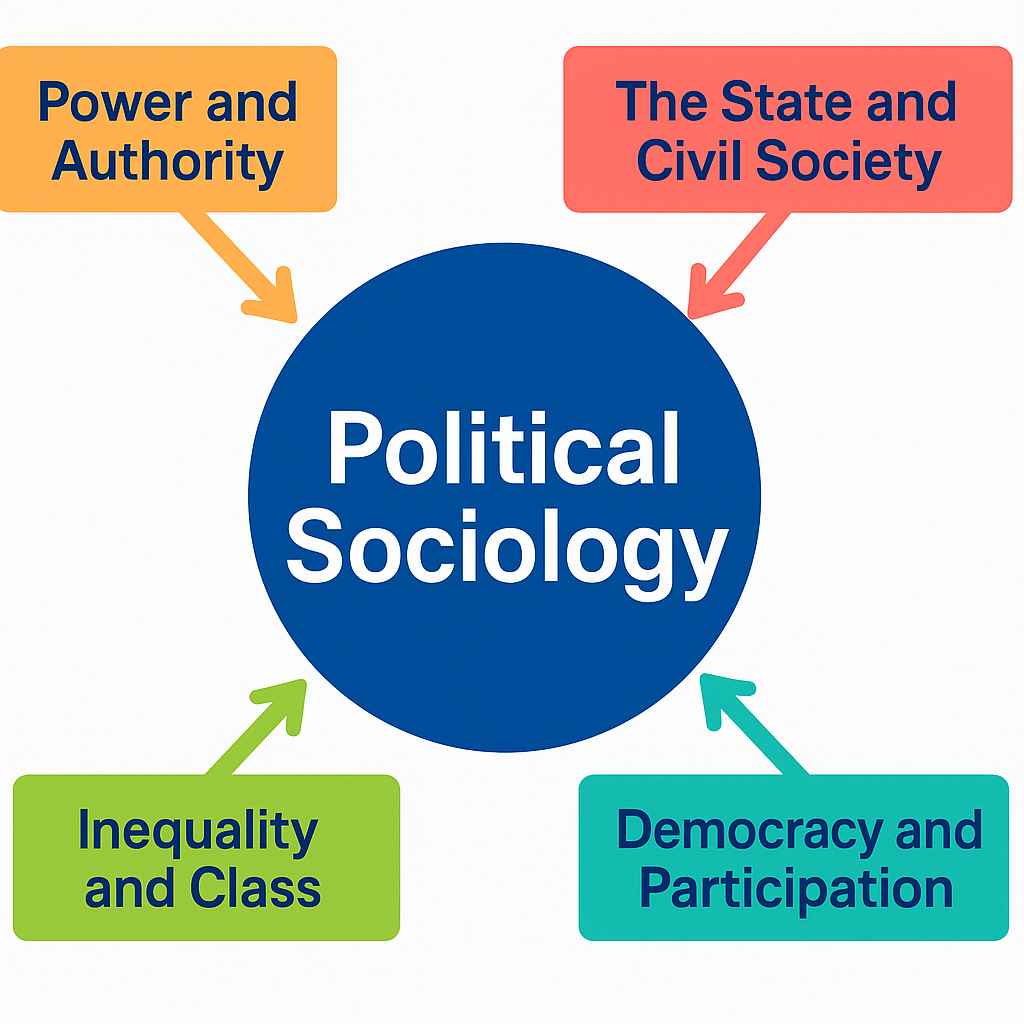

Political sociology is a dynamic subfield of sociology that examines the relationship between society and politics. It investigates how power is distributed, exercised, and challenged within different social contexts. Rather than treating politics as confined solely to governmental institutions or electoral processes, political sociology views power as pervasive—embedded in social structures, cultural practices, economic systems, and interpersonal relationships. It analyzes how political behavior and institutions are influenced by social factors such as class, gender, race, religion, and ideology. Political sociology bridges the disciplines of political science and sociology, emphasizing the importance of social forces in shaping political outcomes and highlighting how political structures, in turn, mold societal norms and relationships. In an era marked by global crises, democratic erosion, identity politics, and mass mobilizations, political sociology offers crucial insights into the functioning and transformation of power across societies.

The Origins and Evolution of Political Sociology

Political sociology emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as sociologists sought to understand the role of the state, authority, and power in rapidly changing industrial societies. Thinkers like Karl Marx, Max Weber, and Émile Durkheim laid the foundations for the field. Marx examined how economic structures and class conflict shape political systems, while Weber analyzed different types of authority and the rationalization of modern governance. Durkheim focused on the moral foundations of society and the role of collective consciousness in political integration. The discipline grew through the 20th century, incorporating diverse perspectives and methodologies. Post-war political sociology focused on electoral behavior, elite theory, and the institutional dynamics of democracy. The 1960s and 1970s saw a shift toward conflict theory, critical perspectives, and analyses of social movements. More recently, political sociology has expanded to include the study of globalization, identity politics, transnational movements, and digital political communication. Its evolution reflects broader changes in the political landscape and demonstrates the discipline’s flexibility in analyzing both macro- and micro-level power relations.

Classical Theories of Power and Authority

Classical sociological theorists have profoundly influenced the conceptualization of power and authority. Karl Marx viewed political power as a reflection of economic relations. According to Marx, the state is an instrument of class domination, serving the interests of the bourgeoisie by maintaining conditions favorable to capital accumulation. In contrast, Max Weber offered a more nuanced view by distinguishing between different types of authority: traditional (based on customs and inherited status), charismatic (based on personal qualities and leadership), and legal-rational (based on rules and procedures). Weber emphasized the role of bureaucracy in modern state structures, arguing that rational-legal authority forms the basis of modern political institutions. Émile Durkheim, while less focused on politics per se, emphasized social cohesion and the collective conscience as foundations for political order. Later theorists, such as Antonio Gramsci, introduced the concept of cultural hegemony to explain how the ruling class maintains control not only through coercion but also by shaping ideology and cultural norms. These foundational theories remain central to political sociology, offering diverse lenses through which power and governance can be analyzed.

The State: Definitions, Functions, and Debates

The state is a central focus of political sociology. It is typically defined as a set of institutions with the authority to make and enforce laws within a given territory. Max Weber famously described the state as the entity that holds a monopoly on the legitimate use of physical force. Political sociologists study the origins of the state, its evolution across time, and its varying forms—from liberal democracies to authoritarian regimes. Functionalist perspectives emphasize the role of the state in maintaining social order and providing public goods. In contrast, conflict theorists argue that the state serves dominant interests and perpetuates inequality. Contemporary debates center on the transformation of the state under globalization. Scholars ask whether the state is weakening in the face of multinational corporations, international organizations, and global financial markets. Others highlight the resilience and adaptability of the state, particularly in managing crises such as pandemics, climate change, or economic collapse. Understanding the nature of the state requires analyzing its institutions, its relationship with civil society, and the social forces that shape its legitimacy and capacity.

Power Beyond the State: Civil Society and Social Movements

While the state wields formal political power, civil society—comprising NGOs, community organizations, advocacy groups, and informal networks—plays a crucial role in shaping political life. Political sociology recognizes that power operates outside formal institutions through discourse, protest, resistance, and everyday practices. Social movements represent a key focus in this area, offering a vehicle for marginalized groups to challenge dominant power structures and advocate for change. Theories of social movements have evolved over time, from resource mobilization theory (emphasizing organizational resources and leadership) to new social movement theory (focusing on identity, culture, and post-materialist values). Political opportunity structures and framing processes are also important concepts in explaining the emergence, strategies, and outcomes of movements. Civil society is a contested space—it can promote democratization and empowerment, but it can also reinforce status quo power structures or serve elite interests. The dynamic relationship between the state and civil society is central to understanding the complexity of political power in contemporary societies.

Political Ideologies and Belief Systems

Political ideologies are systems of ideas that provide a framework for interpreting politics, guiding political behavior, and justifying power. They include liberalism, conservatism, socialism, anarchism, feminism, nationalism, and environmentalism, among others. Each ideology encompasses particular assumptions about human nature, the role of the state, individual rights, economic organization, and social justice. Political sociology examines how ideologies emerge, spread, and influence political institutions and movements. It also explores how belief systems interact with religion, culture, and identity. In modern democracies, ideologies shape party platforms, policy debates, and electoral choices. However, ideological cleavages are not fixed. They evolve in response to historical events, social change, and global developments. The rise of post-ideological or hybrid political movements has led some scholars to argue that ideological boundaries are blurring. Others counter that ideologies remain potent forces that structure political discourse and mobilization. Political sociology provides tools to analyze how ideologies operate at both macro and micro levels—within institutions, discourse, and individual consciousness.

Democracy and Political Participation

Democracy, broadly defined as a system of government based on popular sovereignty, is a central concern of political sociology. The field examines the conditions under which democracies emerge, consolidate, or decline. It also studies the forms and quality of political participation—including voting, campaigning, protesting, and engaging in public deliberation. Democratic theory has evolved from classical models emphasizing direct citizen involvement to more representative models where elected officials act on behalf of the public. Political sociologists assess the health of democracy by examining voter turnout, political efficacy, access to information, and the inclusiveness of institutions. Inequality in participation—based on class, race, gender, or education—can undermine democratic legitimacy. Recent trends, such as voter suppression, political polarization, and the influence of money in politics, raise concerns about democratic backsliding. Participatory and deliberative models of democracy offer alternatives that emphasize citizen engagement, dialogue, and collective decision-making. Political sociology contributes to these debates by analyzing the social foundations of democratic governance and the barriers to meaningful participation.

Political Elites and Leadership

Political elites are those individuals and groups who hold a disproportionate amount of political power and influence, whether through formal office, wealth, media control, or strategic networks. Political sociology critically analyzes the role of elites in shaping policies, agendas, and the broader political climate. Classical elite theorists such as Vilfredo Pareto, Gaetano Mosca, and C. Wright Mills argued that a small group of elites—whether economic, military, or political—tend to dominate all societies, regardless of their democratic or authoritarian nature. Mills’ concept of the “power elite” particularly emphasizes the interlocking relationships between corporate leaders, military generals, and political officials in the U.S., suggesting a concentration of power that undermines democratic ideals. Contemporary political sociologists explore how elites reproduce themselves through exclusive education, social capital, and institutional access, and how this reproduction reinforces inequality. Leadership styles are also a subject of analysis—from charismatic and populist figures to technocratic and managerial ones. The study of elites challenges the notion of equal political participation by revealing how decision-making often remains in the hands of a few.

Class, Capital, and Political Inequality

Economic inequality is a fundamental determinant of political inequality. Political sociology builds on the Marxist tradition in analyzing how class structures shape political power and participation. The capitalist mode of production creates divisions between those who own capital (the bourgeoisie) and those who sell their labor (the proletariat), and this class dynamic is mirrored in the political realm. Access to campaign finance, lobbying, and media ownership allows wealthy individuals and corporations to exert disproportionate influence over policy-making and public discourse. Meanwhile, working-class and marginalized communities often face barriers to political engagement, including lack of time, resources, or representation. Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of “capital”—including social, cultural, and symbolic capital—extends this analysis by showing how non-economic resources also shape political influence. Political inequality is not only about voting rights but also about who sets the agenda, who gets heard, and whose interests are prioritized in policy decisions. Political sociology thus seeks to expose and challenge the mechanisms by which economic hierarchies are translated into political power.

Gender and Politics

Gender is a crucial lens in political sociology for understanding how power and political structures are gendered. Historically, political institutions have been male-dominated, reflecting broader patriarchal norms that exclude women and gender minorities from formal power. Feminist political sociology explores how political systems perpetuate gender inequality, both through overt exclusion and more subtle cultural mechanisms. Topics of interest include women’s representation in government, the gender gap in voting behavior, feminist movements, reproductive rights, and gendered violence. Scholars also examine how political discourse constructs notions of masculinity and femininity, often privileging aggressive, authoritative male leadership while marginalizing collaborative or empathetic forms of power. Intersectional analyses show how gender interacts with race, class, and sexuality to shape political experiences and identities. The struggle for gender equality in politics involves not only increasing the number of women in leadership but also transforming the norms, institutions, and discourses that define political legitimacy. Political sociology provides critical tools for analyzing and challenging the gendered nature of political power.

Race, Ethnicity, and Political Identity

Race and ethnicity are central axes of political identity and conflict. Political sociology investigates how racial and ethnic identities are constructed, mobilized, and institutionalized within political systems. In many countries, race has been used historically to exclude, oppress, or assimilate minority populations—through policies such as segregation, disenfranchisement, or forced assimilation. Even in contemporary democracies, racial disparities in political representation, policing, voting access, and public services remain pervasive. Ethnic nationalism, xenophobia, and racialized political discourse continue to shape electoral outcomes and policy agendas. On the other hand, race and ethnicity can also be powerful bases for resistance and collective action. Civil rights movements, anti-colonial struggles, and indigenous rights campaigns demonstrate the political agency of racialized groups. Political sociologists analyze how race intersects with class, gender, and religion to shape political behavior and policy. They also explore the role of the state in managing diversity, through multiculturalism, affirmative action, or assimilationist policies. In doing so, political sociology sheds light on the dynamics of inclusion and exclusion that define modern polities.

Globalization and Political Transformations

Globalization has dramatically reshaped the political landscape, challenging the traditional nation-state model and creating new forms of political organization and contestation. Political sociology examines how transnational processes—such as global trade, migration, technological innovation, and international governance—affect national politics, identities, and institutions. Multinational corporations, international financial institutions, and global non-governmental organizations now wield considerable influence over domestic policy decisions. Globalization also facilitates the spread of political ideologies, movements, and conflicts across borders. For example, social media has enabled activists to coordinate globally and inspire transnational solidarity, while populist movements borrow rhetoric and tactics from one another across regions. At the same time, globalization has generated backlash, including nationalist and protectionist movements that seek to reassert sovereignty and cultural identity. Political sociology critically analyzes these dynamics, asking how power operates in a world where political authority is increasingly fragmented and dispersed. It also considers the democratic deficit in global governance and the potential for building more inclusive, accountable transnational institutions.

Nationalism and the Politics of Identity

Nationalism is a potent political force that asserts the primacy of national identity, often linking it to a shared culture, language, or ancestry. Political sociology examines how nationalist ideologies emerge, gain legitimacy, and influence state policies and public attitudes. Nationalism can be a unifying force in anti-colonial struggles or state-building projects, but it can also be exclusionary and violent, leading to xenophobia, ethnic cleansing, or war. Scholars differentiate between civic nationalism (based on shared political values and citizenship) and ethnic nationalism (based on shared heritage or bloodlines), though in practice the two often overlap. Identity politics more broadly refers to the mobilization of social identities—such as gender, race, religion, or sexuality—for political purposes. Political sociologists analyze how these identities are socially constructed and politically instrumentalized, often becoming flashpoints in electoral campaigns, policy debates, and cultural conflicts. The politics of identity reveals how group belonging shapes political interests, grievances, and allegiances, and how dominant groups may deploy identity narratives to maintain power or marginalize others.

Political Violence, War, and Conflict

Political violence—ranging from riots and revolutions to terrorism and state repression—is a critical area of analysis in political sociology. Violence is not merely the breakdown of politics but often an extension of it through other means, reflecting deep-seated social conflicts and structural inequalities. Sociologists study the causes and consequences of political violence, including the role of state repression, ethnic tensions, ideological extremism, and economic deprivation. Theories of revolution, such as those by Theda Skocpol and Charles Tilly, emphasize the importance of state capacity, international pressures, and social mobilization in producing revolutionary change. Meanwhile, terrorism and insurgency are analyzed not only in terms of ideology but also as strategic responses to exclusion or occupation. War, as a form of organized violence between states or groups, has far-reaching consequences for political institutions, social cohesion, and economic development. Political sociology examines both the macro-level conditions that lead to conflict and the micro-level dynamics of radicalization and recruitment. Additionally, it considers how societies remember and recover from political violence—through truth commissions, memorialization, and transitional justice.

Media, Communication, and Political Discourse

In the modern age, media is a central arena of political power. Political sociology examines how information, narratives, and ideologies are produced, disseminated, and consumed through media channels. Traditional mass media (television, radio, newspapers) and digital platforms (social media, blogs, podcasts) play a crucial role in shaping public opinion, framing political issues, and influencing electoral outcomes. The concept of framing, developed by Erving Goffman and extended by media sociologists, highlights how the way an issue is presented can influence how it is interpreted. Agenda-setting theory shows how media prioritizes certain topics over others, shaping public perception of what matters. Political communication is also shaped by ownership structures: concentrated media ownership can lead to biased reporting and the marginalization of dissenting voices. The rise of social media has democratized content production but also facilitated the spread of misinformation, echo chambers, and algorithmic polarization. Political sociology critically analyzes how communication technologies affect civic engagement, deliberation, and power relations, and how discourse reflects and reinforces social hierarchies.

Religion and Politics

Religion remains a powerful force in political life, influencing laws, values, identities, and conflicts. Political sociology explores how religious institutions and beliefs intersect with state power, political ideologies, and civil society. Secularization theory, once dominant, predicted a decline in religious influence as societies modernized. However, the resurgence of political religion—evident in Christian fundamentalism, political Islam, Hindu nationalism, and Buddhist populism—has challenged this view. In some cases, religion provides moral legitimacy for political regimes; in others, it acts as a mobilizing force for resistance and social justice. Religious movements have been central to many historical and contemporary struggles, from the U.S. civil rights movement to anti-colonial independence campaigns. Political sociologists also study the role of religion in shaping public policy on issues like abortion, education, gender rights, and marriage. The church-state relationship varies widely across societies, from official theocracies to secular democracies. Political sociology provides tools to understand how religious and political spheres overlap and how this interaction shapes both governance and everyday life.

The Rise of Populism and Authoritarianism

The 21st century has witnessed a global surge in populist and authoritarian politics. Populism, which pits “the people” against “the elite,” is not tied to a specific ideology and can manifest on the left or right. Political sociologists analyze the conditions that give rise to populism, including economic insecurity, cultural backlash, and political disenchantment. Populist leaders often present themselves as outsiders who speak for the “silent majority,” using charismatic authority and direct communication—often through social media—to bypass traditional institutions. At the same time, authoritarian tendencies have re-emerged in democracies and intensified in existing autocracies. These include attacks on the press, the judiciary, and opposition parties, as well as the curtailment of civil liberties. Political sociology examines how such regimes maintain support through propaganda, nationalism, patronage, and surveillance. It also investigates the social bases of authoritarianism—who supports it and why. These developments challenge assumptions about the inevitability of democratic progress and call for renewed attention to the sociological foundations of political order and disorder.

Comparative Political Systems

Political sociology often employs comparative methods to analyze how different political systems operate and how they shape social outcomes. Democracies, monarchies, authoritarian regimes, theocracies, and hybrid systems are all studied to understand how institutions are structured, how power is distributed, and how citizens interact with the state. Comparative political sociology asks why some societies maintain stable democratic institutions while others experience coups, revolutions, or repression. It examines the impact of colonial legacies, economic development, civil society, and cultural norms on political trajectories. For example, Scandinavian countries are often cited for their egalitarian welfare states, while the U.S. exhibits high levels of political polarization and inequality. Authoritarian regimes like China demonstrate the possibility of economic growth without liberal democracy, challenging Western assumptions about modernization. Comparative analysis helps political sociologists identify patterns, test theories, and explore the complex interplay between culture, economy, and governance. It also highlights the contingency of political development and the importance of historical and contextual factors.

Political Sociology in the 21st Century

In the 21st century, political sociology faces a rapidly changing world marked by unprecedented challenges and transformations. The climate crisis is reshaping political priorities and creating new forms of environmental activism and governance. Digital technologies are transforming how citizens engage, how states surveil, and how political influence is wielded. Migration and demographic shifts are changing the composition of electorates and altering the politics of identity. The COVID-19 pandemic revealed both the capacities and failures of states and brought renewed attention to public health, inequality, and global cooperation. Meanwhile, political polarization, disinformation, and declining trust in institutions pose existential threats to democratic systems. In response to these developments, political sociology continues to evolve, incorporating interdisciplinary methods, global perspectives, and intersectional frameworks. It seeks to understand not only how power operates in traditional political settings but also how it is contested and reimagined in everyday life, cultural spaces, and transnational arenas. As a discipline, political sociology remains vital for anyone seeking to understand the forces that shape the political world and how we might envision more just and democratic futures.

Conclusion

Political sociology provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the social foundations, expressions, and consequences of power. It goes beyond formal political institutions to examine how power is produced, distributed, contested, and experienced across different domains of life. Whether analyzing voter behavior, elite domination, revolutionary movements, or the intersection of race and politics, political sociology reveals the embeddedness of the political in all aspects of society. It uncovers how structures of class, gender, race, religion, and culture shape political dynamics and how, in turn, politics structures opportunities, identities, and inequalities. As the global political landscape continues to evolve—shaped by crises, movements, technologies, and ideologies—political sociology remains an indispensable tool for critical analysis and engaged citizenship. It challenges us to not only understand the world but to consider how it might be transformed.

References

- Mills, C. Wright. The Power Elite. Oxford University Press, 1956.

- Skocpol, Theda. States and Social Revolutions: A Comparative Analysis of France, Russia, and China. Cambridge University Press, 1979.

- Gramsci, Antonio. Selections from the Prison Notebooks. International Publishers, 1971.

- Tilly, Charles. Social Movements, 1768–2004. Paradigm Publishers, 2004.

Culture lag is defined as the time between the appearance of a new material invention and the making of appropriate adjustments in corresponding area of non-material culture. This time is often long. It was over fifty years, for example, after the typewriter was invented before it was used systematically in offices. Even today, we may have a family system better adapted to a farm economy than to an urban industrial one, and nuclear weapons exist in a diplomatic atmosphere attuned to the nineteenth century. As the discussion implies, the concept of culture lag is associated with the definition of social problems. Scholars envision some balance or adjustment existing between material and non-material cultures. That balance is upset by the appearance of raw material objects. The resulting imbalance is defined as a social problem until non-material culture changes in adjustment to the new technology.

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|