Home >> Marriage Family and Kinship >> Kinship

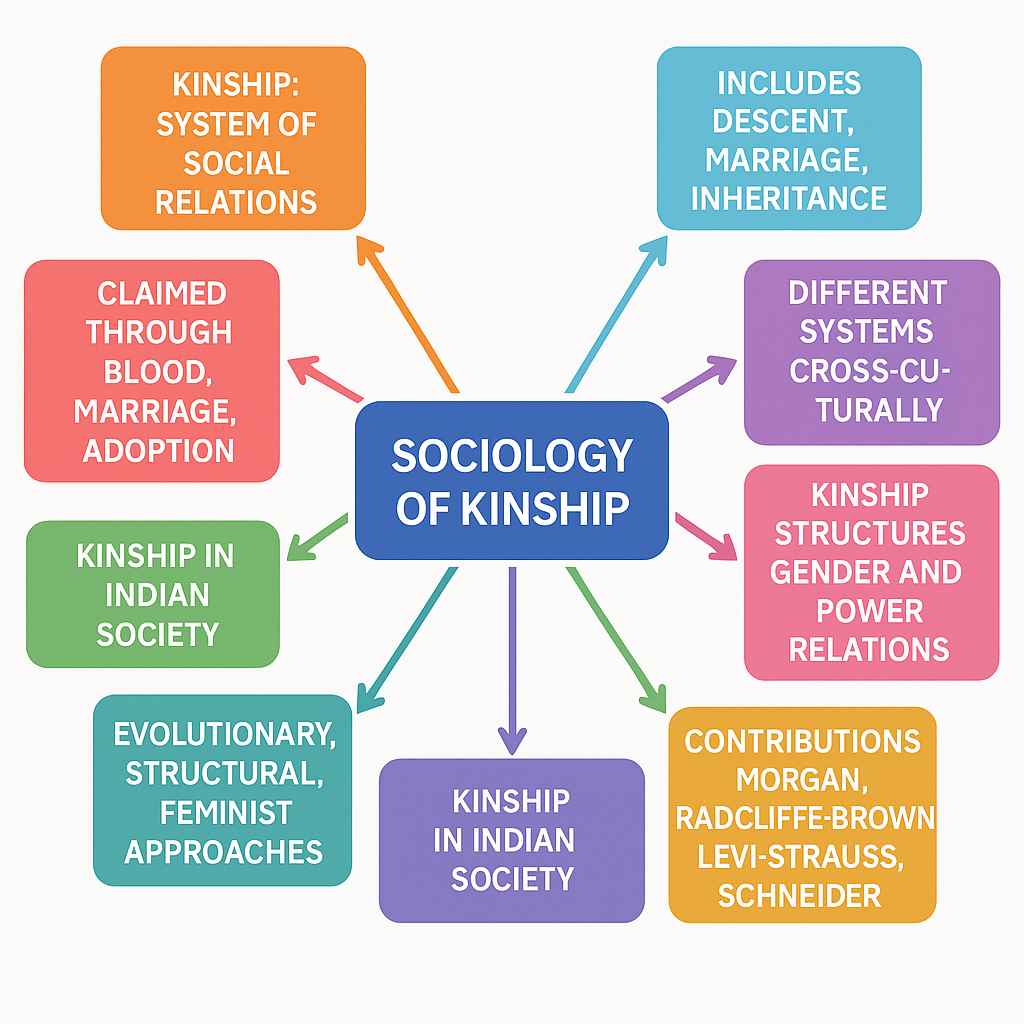

Sociology of Kinship

Index

- Introduction to Kinship

- Meaning and Scope of Kinship

- Key Concepts in Kinship Studies

- Theoretical Approaches to Kinship

- Cross-Cultural Kinship Systems

- Kinship in Indian Society

- Kinship and Marriage

- Contributions of Key Thinkers in Kinship Studies

- Contemporary Issues in Kinship

- Kinship, Gender, and Power

- Conclusion

Introduction to Kinship

Kinship is one of the most fundamental and universally acknowledged concepts in sociology and anthropology. It refers to the web of social relationships that form an important part of the lives of all humans in all societies, serving as the basic framework for social organization, reproduction, inheritance, and social obligations. Unlike mere biological connections, kinship is a culturally constructed system that defines roles, expectations, and behavioral patterns among relatives. In traditional societies, kinship determines rights and duties in areas such as marriage, residence, descent, and inheritance, while even in modern industrial societies, kinship remains influential in shaping social structure and familial norms. Understanding kinship systems is crucial to grasping how human societies organize themselves around shared identities and obligations.

Kinship provides a lens through which sociologists explore how different cultures interpret familial ties, regulate marriage practices, and structure authority and inheritance. It transcends biological links to incorporate social and symbolic relations, often enforced through rituals, taboos, and rules governing procreation, alliance, and descent. With the evolution of society, the study of kinship has expanded beyond the family unit to incorporate themes like gender, power, economy, and cultural symbolism, illustrating how kinship systems are not static but evolve with changing social and economic contexts.

Meaning and Scope of Kinship

The term “kinship” refers to the relationships between individuals that are defined through blood (consanguinity), marriage (affinity), and in some cases, adoption or ritual relationships (fictive kinship). Kinship is not merely a private or familial matter but an institutional arrangement that provides social order and continuity. It encompasses various practices and norms that determine how individuals relate to one another, how descent is traced, who one may or may not marry, and how resources and responsibilities are allocated among relatives.

The scope of kinship studies includes both the micro and macro levels of analysis. At the micro level, kinship involves examining interpersonal relationships, emotional ties, and the everyday functioning of families. At the macro level, it includes the study of lineage, clan systems, tribal organization, and the role of kinship in political and economic structures. Kinship ties serve as critical units of social support, economic cooperation, and cultural transmission, especially in pre-industrial societies where formal institutions were weak or non-existent. Thus, kinship systems are pivotal in understanding the broader structure and functioning of any society.

Key Concepts in Kinship Studies

Kinship studies are built around several core concepts, including descent, lineage, clan, kindred, marriage, residence patterns, and inheritance. These concepts help sociologists and anthropologists analyze how societies organize themselves and maintain continuity.

Descent refers to the way people trace their ancestry. It can be patrilineal (through the father’s line), matrilineal (through the mother’s line), or bilateral (through both). Lineage refers to a group of people who claim descent from a common ancestor and can trace the connection genealogically. A clan is a larger unilineal descent group that claims descent from a common ancestor but often cannot trace it genealogically. Kindred is an ego-centered group consisting of all relatives known to a specific individual, which is significant in bilateral descent systems.

Marriage rules include endogamy (marriage within a group), exogamy (marriage outside the group), monogamy, and polygamy (polygyny and polyandry). Residence patterns—such as patrilocality, matrilocality, neolocality, and avunculocality—determine where a couple lives after marriage. Inheritance systems dictate how property and social status are passed down, and they are often tied to descent and residence patterns. These concepts are not isolated but interlinked, shaping the social organization and cultural norms of a community. For example, patrilineal descent systems often correlate with patrilocal residence and patrilineal inheritance, creating a coherent social structure where property, power, and identity are aligned.

Theoretical Approaches to Kinship

Over time, sociological and anthropological understandings of kinship have evolved through several theoretical approaches. Each approach reflects the changing epistemologies and focuses within the discipline.

a. Evolutionary and Comparative School

The earliest kinship theories emerged from 19th-century evolutionism,

represented by scholars like Lewis Henry Morgan, Edward B. Tylor, and James

Frazer. Morgan’s seminal work Ancient Society (1877) introduced the idea of

social evolution from savagery to barbarism to civilization, using kinship as a

key organizing principle. He distinguished between classificatory and

descriptive kinship systems and attempted to reconstruct the origins of the

family and human society through comparative methods. He identified

different stages of family evolution, including the consanguine family,

punaluan family, and monogamous family.

Although criticized for its ethnocentrism and speculative nature, the

evolutionary school laid the groundwork for systematic kinship studies. It

emphasized the importance of kinship in understanding social organization,

even if its assumptions about linear progress and cultural superiority were

later rejected.

b. Structural-Functionalism

The structural-functional approach, associated with A.R. Radcliffe-Brown and

Bronislaw Malinowski, views kinship as an institution that fulfills important

social functions. Radcliffe-Brown, in particular, saw kinship as a system of

relationships that maintains social order and cohesion. He emphasized the

normative aspects of kinship and how roles and expectations are structured

within a system of descent and alliance.

Malinowski, based on his fieldwork among the Trobriand Islanders, argued

that the family is a universal institution that fulfills the biological and

emotional needs of individuals, especially children. He challenged the notion

that biological paternity is necessary for fatherhood, showing that in

matrilineal societies, social roles of fatherhood can be performed by maternal

uncles.

Structural-functionalists prioritized fieldwork and empirical observation,

offering detailed accounts of how kinship operates in specific societies.

However, their tendency to view kinship systems as static and overly

harmonious has been critiqued by later theorists.

c. Alliance Theory (Structuralism)

The alliance theory, associated with Claude Lévi-Strauss, marked a shift from

descent-based analysis to the importance of marriage alliances in organizing

societies. In his book The Elementary Structures of Kinship (1949),

Lévi-Strauss argued that kinship is not just about descent but about the

exchange of women between groups, which creates alliances and social

cohesion.

He introduced the concept of the “atom of kinship,” a basic kinship unit

consisting of a man, his sister, his wife, and his wife’s brother. For

Lévi-Strauss, the incest taboo is universal because it facilitates the exchange of

women, thereby integrating groups into larger social networks. His approach,

rooted in structuralism, viewed kinship as a system of symbols and meanings,

influenced by the binary oppositions inherent in human cognition.

Alliance theory has been influential but also criticized for overemphasizing

symbolic exchange and ignoring actual practices, gender agency, and power

dynamics within families.

d. Feminist and Post-Structuralist Approaches

From the 1970s onward, feminist scholars like Gayle Rubin, Carole Stack, and

Judith Butler challenged the androcentric and Eurocentric assumptions of

earlier kinship theories. Rubin’s essay “The Traffic in Women” (1975) critiqued

how women are exchanged like commodities in kinship systems, reinforcing

patriarchy and gender oppression. Feminists argued that kinship systems

should be analyzed not just as neutral structures but as systems imbued with

power, ideology, and inequality.

Post-structuralists and queer theorists, such as Butler, questioned the

heteronormative assumptions of kinship and emphasized the performative

aspects of gender and family. They highlighted the importance of recognizing

diverse family forms, including same-sex families, chosen families, and

non-biological parenthood. This led to the broadening of kinship studies to

include issues of identity, sexuality, and cultural representation.

Cross-Cultural Kinship Systems

Kinship systems vary significantly across cultures, reflecting the diversity of

social organization and cultural values. Anthropologists have classified

kinship terminologies into different types, including Eskimo, Hawaiian,

Iroquois, Sudanese, Crow, and Omaha systems. These systems determine how

relatives are classified and addressed, revealing underlying principles of

descent, alliance, and residence.

In Eskimo systems (common in Western societies), nuclear family members

are distinguished from extended kin. In Hawaiian systems, generational

differences are emphasized, and all relatives of the same generation are

addressed similarly. Iroquois and Crow systems reflect unilineal descent, with

specific terms for parallel and cross-cousins, affecting marriage rules.

Among the Nuer of Sudan, studied by Evans-Pritchard, kinship is tied closely

to lineage and political organization. In Indian society, kinship is deeply

intertwined with caste, religion, and regional variations. For example, in

North India, patrilineal and patrilocal systems dominate, with strict rules

against cousin marriage. In South India, especially among Dravidian

communities, cross-cousin marriage is preferred, reflecting a different logic of

alliance.

These cross-cultural studies illustrate how kinship is not a universal template

but a culturally specific institution that adapts to social, economic, and

ecological conditions.

Kinship in Indian Society

Kinship in Indian society is a complex and richly layered system influenced by factors such as caste, religion, region, language, and economic organization. Indian kinship patterns reveal a strong orientation toward collectivism and social obligation, particularly in rural and traditional settings. The Indian kinship system is deeply embedded in the hierarchical social structure of caste (varna-jati), and it influences patterns of marriage, inheritance, residence, and ritual duties.

Indian kinship is generally described through three interrelated components:

gotra (patrilineal clan), sapinda (shared bodily substance or lineage), and

samānōda (ritual proximity). In North India, kinship is typically patrilineal,

patrilocal, and governed by strong exogamous rules. For instance, people

belonging to the same gotra are prohibited from marrying one another, based

on the belief that they descend from a common ancestor. The notion of

“sapinda exogamy” further restricts marriage among individuals who share

common ancestors up to five generations on the father’s side and three on the

mother’s side.

In contrast, South Indian kinship allows for cross-cousin marriage, especially

between a man and his mother’s brother’s daughter (MBD). This reflects a

different kinship logic, where marriage within the kin group helps consolidate

property, lineage continuity, and familial alliances. Matrilineal kinship is also

found among certain communities such as the Nairs of Kerala, where lineage

and inheritance are traced through the female line, and maternal uncles play a

major role in child-rearing and property transmission.

The Indian kinship system is also tightly linked to ritual purity and pollution, particularly in relation to caste. Ritual obligations such as shraddha (ancestral rites) and gotra rites are kinship duties performed predominantly by male descendants, which reinforce lineage-based identities. The system operates not only on kinship bonds but also through ideological frameworks, ensuring the reproduction of caste, gender roles, and economic responsibilities across generations.

Kinship and Marriage

Marriage, as a central institution in kinship systems, is governed by cultural rules of alliance, residence, and descent. It not only creates conjugal bonds but also forms alliances between families, lineages, and even communities. In kinship studies, marriage rules are typically divided into prescriptive, preferential, and proscriptive types.

Prescriptive marriage rules require marriage with a specific category of

relatives (e.g., cross-cousins), while preferential rules suggest but do not

mandate such unions. Proscriptive rules, on the other hand, forbid marriage

within a particular group (e.g., gotra or sapinda exogamy in North India).

These rules function to regulate sexual access, prevent incest, and promote

social cohesion through alliance-building.

Marriage also determines residence patterns such as:

- Patrilocal (wife moves to husband’s household)

- Matrilocal (husband moves to wife’s household)

- Neolocal (independent residence)

- Avunculocal (residing with the maternal uncle, often in matrilineal societies)

In traditional societies, marriage is also linked to the bride price or dowry system, which symbolizes the transfer of rights and duties. Dowry practices, particularly in South Asia, are not only economic transactions but also reinforce kinship hierarchies, gender subordination, and class distinctions. Through marriage, kinship systems reproduce not only biological descent but also social structures, including class, caste, and gender hierarchies.

Contributions of Key Thinkers in Kinship Studies

Lewis Henry Morgan

Morgan was among the first to conduct systematic kinship studies. His work Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family (1871) and Ancient Society (1877) categorized kinship systems globally and proposed a universal evolutionary trajectory of family systems. He distinguished between classificatory kinship (where relatives are grouped into broader categories) and descriptive kinship (where each relative has a unique term). His work inspired Marx and Engels, particularly in the analysis of the family as an economic institution.

A.R. Radcliffe-Brown

Radcliffe-Brown emphasized the structural-functional role of kinship in maintaining societal equilibrium. He viewed kinship as a network of roles and norms that ensured the integration of individuals into social institutions. His famous study on the Andaman Islanders and his conceptualization of “jural rules” in kinship set the foundation for kinship as a system of obligations and sanctions.

Bronislaw Malinowski

Malinowski provided a more psychological and functional interpretation of kinship, based on his fieldwork in the Trobriand Islands. He argued that biological fatherhood is not necessary for kinship roles, especially in matrilineal societies where maternal uncles play paternal roles. His concept of nuclear family as a universal challenged earlier evolutionary models and emphasized emotional ties.

Claude Lévi-Strauss

Lévi-Strauss revolutionized kinship theory with his alliance theory, where the exchange of women among groups created enduring alliances. His structuralist method viewed kinship as a symbolic system governed by rules of reciprocity and opposition. His idea of the incest taboo as a cultural universal that promotes alliance rather than mere avoidance of inbreeding has had lasting influence.

David Schneider

In his work American Kinship: A Cultural Account, Schneider argued that kinship is not a natural or biological category but a cultural construct shaped by symbols and meanings. He criticized earlier theories for treating kinship as a universal structure and called for a more interpretive and ethnographic approach to understand how kinship is defined within specific cultures.

Gayle Rubin

Rubin’s essay “The Traffic in Women” argued that kinship systems reproduce gender inequality by treating women as objects of exchange. Her Marxist-feminist perspective linked kinship to the political economy and saw marriage as a transaction that reinforces male dominance. Rubin’s work influenced both feminist kinship studies and queer theory.

Janet Carsten

Carsten introduced the concept of “relatedness” to move beyond rigid biological models of kinship. Based on her work in Malaysia, she argued that kinship is made through everyday practices such as sharing food, caregiving, and co-residence. Her approach helped reconceptualize kinship in terms of processes and experiences rather than fixed structures.

Contemporary Issues in Kinship

In recent decades, kinship studies have expanded to include non-traditional

family forms, transnational families, surrogacy, adoption, and queer kinship.

These developments reflect both the changing nature of family structures and

the critiques of essentialist, Eurocentric models of kinship.

In many parts of the world, the traditional nuclear or joint family is giving way

to fragmented or chosen families, especially in urban settings. Surrogacy and

reproductive technologies have challenged the idea that kinship is grounded

in biology, raising ethical and legal questions about motherhood, fatherhood,

and parental rights.

Queer kinship, as discussed by scholars like Kath Weston and Judith Butler,

refers to families formed through non-heteronormative practices, such as

same-sex parenting, cohabitation without marriage, or kinship based on care

rather than blood. These forms defy traditional definitions of family and

demand a broader, more inclusive understanding of kinship.

In the context of globalization and migration, transnational kinship networks

have emerged, where kin relations are maintained across borders through

communication technologies, remittances, and periodic visits. These new

patterns of relatedness show that kinship is not only rooted in geography or

co-residence but is also shaped by mobility, economy, and technology.

Kinship, Gender, and Power

A major shift in kinship studies involves the interrogation of power dynamics

within kinship relations. Kinship systems often reproduce patriarchy, through

mechanisms such as male lineage preference, patrilocality, control over

women’s sexuality, and inheritance laws. Feminist scholars argue that kinship

is not just a system of relationships but also a structure of inequality, where

control over women’s bodies and labor is institutionalized.

The intersection of kinship and caste in India reinforces gender

subordination. For example, caste endogamy and gotra exogamy serve to

regulate women’s sexual behavior and preserve caste purity. Dowry and

marriage rituals act as instruments of both economic transaction and

gendered control.

Moreover, kinship can also be a source of resistance and agency. Women’s

networks, sisterhoods, and maternal kinship ties can challenge patriarchal

structures by offering alternative sources of support, identity, and

empowerment. The “feminization of kinship”, observed in both rural and

urban settings, highlights how caregiving, emotional labor, and social

reproduction are often disproportionately managed by women.

Conclusion

The study of kinship, once seen as a static and technical domain of

anthropological inquiry, has evolved into a dynamic field that intersects with

issues of gender, power, economy, and culture. From the early evolutionary

theorists like Morgan to structural-functionalists like Radcliffe-Brown, from

Lévi-Strauss’s alliance theory to contemporary feminist and post-structuralist

critiques, kinship has remained a central concern in understanding the fabric

of human society.

Today, the relevance of kinship studies extends beyond tribal or pre-modern

societies to address the complexities of family, identity, and belonging in a

globalized, technologically mediated world. Kinship is not merely about blood

ties or marital bonds but about the social practices and cultural meanings that

define how we relate to one another, care for each other, and imagine

community and continuity.

By moving beyond rigid typologies and embracing the fluidity of relatedness,

contemporary kinship studies offer a more inclusive and nuanced

understanding of human social life. Whether in traditional joint families,

matrilineal lineages, transnational migrant households, or chosen queer

families, the patterns of kinship continue to shape and reflect the moral,

political, and economic foundations of society.

References

- Morgan, Lewis Henry. Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family, 1871.

- Radcliffe-Brown, A.R. Structure and Function in Primitive Society, 1952.

- Malinowski, Bronislaw. The Sexual Life of Savages in North-Western Melanesia, 1929.

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude. The Elementary Structures of Kinship, 1949.

- Schneider, David. American Kinship: A Cultural Account, 1968.

- Rubin, Gayle. “The Traffic in Women: Notes on the ‘Political Economy’ of Sex”, 1975.

- Carsten, Janet. After Kinship, 2004.

- Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble, 1990

- Weston, Kath. Families We Choose: Lesbians, Gays, Kinship, 1991.

- Uberoi, Patricia. Family, Kinship and Marriage in India, 1993.

Kinship is the relation by the bond of blood, marriage and includes kindered ones. It represents one of the basic social institutions. Kinship is universal and in most societies plays a significant role in the socialization of individuals and the maintenance of group solidarity.

It is very important in primitive societies and extends its influence on almost all their activities.A.R Radcliffe Brown defines kinship as a system of dynamic relations between person and person in a community, the behavior of any two persons in any of these relations being regulated in some way and to a greater or less extent by social usage.

|

|

Affinal and Consanguineous kinship

Relation by the bond of blood is called consanguineous kinship such as parents and their children and between children of same parents. Thus son, daughter, brother, sister, paternal uncle etc are consanguineous kin. Each of these is related through blood. Kinship due to marriage is affinal kinship. New relations are created when marriage takes place. Not only man establishes relationship with the girl and the members of her but also family members of both the man and the woman get bound among themselves. Kinship includes Agnates (sapindas, sagotras); cognates (from mother's side) and bandhus (atamabandhus, pitrubandhus, and matrubandhus).

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|