Urbanisation

Index

- The Urban Way of Life

- Urbanisation in India: Patterns, Drivers, and Challenges

- Contemporary Thinkers on Urbanisation

- Manuel Castells: Collective Consumption and Urban Movements

- David Harvey: Accumulation by Dispossession and Right to the City

- Saskia Sassen: Global Cities and Expulsions

- Smart Cities Mission and AMRUT: Urban Policy Frameworks in India

- Informal Economy, Migration, and the Urban Poor

- Gender, Caste, and Exclusion in Urban Space

- Environmental Crisis, Sustainability, and the Future of Urbanisation

- Conclusion

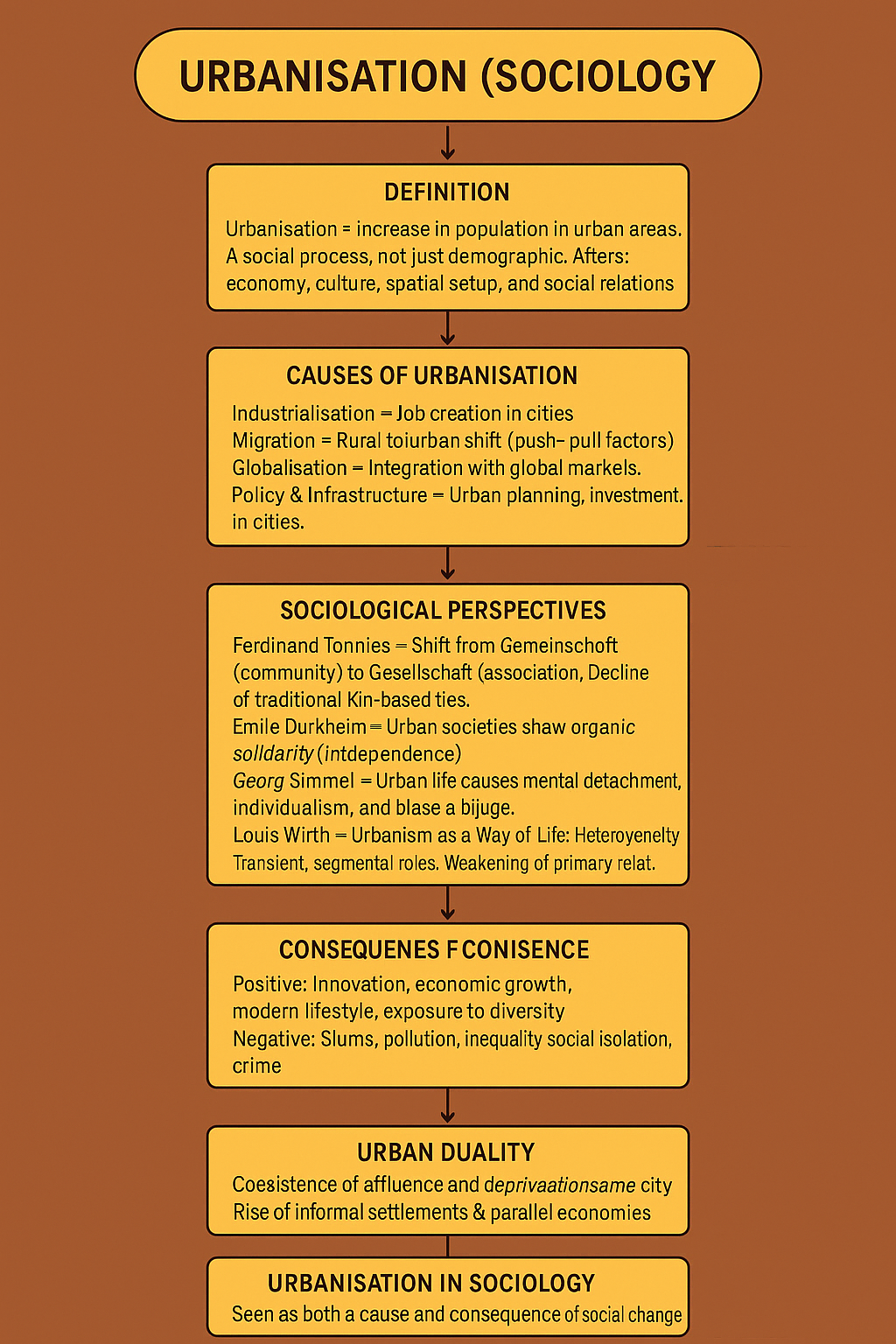

Urbanisation refers to the process by which an increasing proportion of a

population comes to reside in urban areas, leading to the growth and expansion

of towns and cities. It is not merely a demographic shift but a complex social

transformation that alters economic systems, cultural patterns, spatial

arrangements, and social relations. Urbanisation in sociology is understood as

both a cause and consequence of social change—shaped by industrialisation,

migration, globalisation, and policy regimes.

At its core, urbanisation represents a shift from Gemeinschaft to Gesellschaft,

as described by Ferdinand Tönnies—moving from close-knit, tradition-bound

communities to impersonal, contractual, and bureaucratically managed urban

societies. This transition brings with it new forms of social organisation, such

as nuclear families, voluntary associations, and formal economic systems, while

often weakening traditional kinship bonds and community-based controls.

From a functional perspective, urbanisation fosters economic growth by

concentrating labor, capital, and infrastructure. Cities act as hubs of

innovation, trade, services, and education, contributing to national

development. However, this same process also generates dysfunctions—rising

inequality, housing shortages, slums, pollution, crime, and the weakening of

social solidarity.

Urbanisation is closely tied to migration, especially rural-to-urban migration,

which reflects both push factors (poverty, lack of employment, agrarian

distress) and pull factors (job opportunities, better services, modern lifestyles).

This migration fuels the informal sector and unregulated settlements, resulting

in the coexistence of affluence and deprivation within the same urban space—a

phenomenon often called the “urban duality.”

Louis Wirth’s classic work on “Urbanism as a Way of Life” (1938) explains that

urban settings foster a particular mode of life marked by individualism,

rationality, diversity, and social isolation. The city becomes a site of multiple,

transient relationships—where people are constantly surrounded yet often feel

alone. Wirth argues that urbanisation weakens primary relationships and

increases reliance on secondary and impersonal ties.

In the Indian context, urbanisation has accelerated since the post-liberalisation

period of the 1990s, driven by the rise of the service sector, infrastructure

projects, and private real estate. Yet, this growth has been uneven and

exclusionary. Cities like Delhi, Mumbai, and Bangalore have emerged as global

nodes, but millions continue to live in slums with poor sanitation, insecure

tenure, and limited access to education and healthcare.

Urban sociologists have also emphasized the concept of the “Right to the

City”—a demand for more equitable, participatory, and inclusive urban spaces.

This approach critiques top-down planning and advocates for the inclusion of

marginalised groups—slum dwellers, women, migrants, and the urban

poor—in decision-making processes.

Importantly, urbanisation is now deeply intertwined with technology and

surveillance, leading to the rise of “Smart Cities” and “Digital Urbanism.”

While these initiatives promise efficiency and innovation, they also risk creating

“techno-elitist” spaces that exclude the poor and deepen digital divides.

Urbanisation is also a site of resistance and grassroots innovation. Movements

for housing rights, environmental justice, and equitable public transport

represent urban struggles that reflect deeper structural inequalities in Indian

cities. Urbanisation, therefore, is not just a demographic or infrastructural

phenomenon—it is a contested social process shaped by power, class, gender,

caste, and state policy.

Introduction: Understanding Urbanisation as Social Transformation

Urbanisation is not merely the process of increasing concentration of

population in urban areas; it is a profound transformation in the structure of

society, modes of livelihood, spatial arrangements, and cultural life. From a

sociological standpoint, urbanisation signifies a transition from rural, agrarian,

kinship-bound communities to urban, industrialised, and bureaucratic forms

of association. It entails not only demographic and spatial expansion of cities

but also a reorganisation of human relationships, institutions, and cultural

values. Urbanisation reflects the dynamics of capitalism, state policy,

technological change, and global integration, making it a deeply contested and

layered phenomenon.

In the classical sociological tradition, Ferdinand Tönnies distinguished between

Gemeinschaft (community) and Gesellschaft (association), suggesting that

urbanisation symbolised a shift from traditional, emotion-based social ties to

rational, contractual, and impersonal relationships. Emile Durkheim viewed

urban societies as based on organic solidarity—complex interdependence

among specialised individuals. Georg Simmel, in his essay The Metropolis and

Mental Life, noted how urban life fosters rationality, individualism, and a blasé

attitude due to constant sensory overload and anonymity. These thinkers laid

the foundation for understanding urbanisation not just as a spatial shift but as

a reconfiguration of human consciousness and interaction.

The Urban Way of Life: Wirth and the Sociological Imagination

A key sociological text in the study of urbanisation is Louis Wirth’s (1938)

Urbanism as a Way of Life. He argued that the urban environment gives rise to

a distinctive social character defined by heterogeneity, transience, and

segmental roles. Urban life is marked by impersonal, superficial relationships

where primary ties weaken and secondary, formal associations dominate. The

urbanite develops a sense of reserve, emotional detachment, and tolerance of

diversity. Wirth’s formulation remains relevant in explaining the nature of

modern cities, though scholars now emphasise that urban experiences also

include resistance, collective identity, and new forms of solidarity.

In India, the coexistence of tradition and modernity within cities challenges

some of Wirth’s assumptions. For instance, kinship, caste networks, and

religious identities continue to influence urban housing, labour, and marriage

patterns. Yet, urbanisation has undeniably altered the landscape of everyday

life—shifting people from caste-based occupations to service sector jobs,

transforming family structures, and introducing new aspirations.

Urbanisation in India: Patterns, Drivers, and Challenges

India’s urbanisation trajectory has been uneven, informal, and exclusionary.

According to Census 2011, around 31% of India’s population lived in urban

areas—a figure projected to rise to nearly 40% by 2036. Unlike the West, where

urbanisation was driven by industrialisation, in India, it has been shaped by

migration, reclassification of rural areas, and urban sprawl. Post-1991 economic

liberalisation accelerated urban growth, particularly in sectors like IT, real

estate, retail, and logistics. Cities such as Bengaluru, Hyderabad, and

Gurugram became global service hubs, attracting investments and skilled

migrants.

Yet, this urban growth has been deeply unequal. A handful of metropolitan

regions absorb most of the investment and migration, while smaller towns

struggle with poor infrastructure. Furthermore, rural-urban migration often

leads to informal settlements or slums, where migrants face precarity, poor

sanitation, insecure tenure, and limited access to services. The informal sector

employs over 80% of the urban workforce, revealing a paradox—cities produce

wealth but fail to ensure dignified lives for most of their inhabitants.

Contemporary Thinkers on Urbanisation: Castells, Harvey, and Sassen

Contemporary sociological and urban theory has added depth to the

understanding of urbanisation by linking it to capital accumulation,

globalisation, and resistance. Manuel Castells, in his theory of collective

consumption, emphasised how the state’s provision of housing, transport,

education, and public services is central to sustaining capitalist urbanisation.

He argued that when these services are denied or commodified, urban

movements emerge in resistance—particularly among the working classes and

urban poor. In India, such movements are evident in slum dwellers’ struggles

for tenure, protests against forced evictions, and campaigns for inclusive

housing.

David Harvey, a Marxist geographer, introduced the idea of “accumulation by

dispossession”, where urban land and resources are privatised, commodified,

and used for speculative investment. Cities become centres for capital

circulation through real estate development, infrastructure projects, and

gentrification. This logic is visible in Indian megacities—where land

acquisition for metro rail, expressways, or smart city projects often displaces

informal workers and indigenous communities. Harvey’s call for a “Right to

the City” is a demand for reclaiming urban spaces as democratic, participatory,

and socially just.

Saskia Sassen, in her work on the Global City, highlights how cities become

command centres of finance, migration, and information flows. Global cities

like New York, London, and Tokyo are replicated in Indian contexts such as

Mumbai, Bengaluru, and Gurugram. These cities are marked by luxury

enclaves, financial districts, and IT parks—coexisting with slums, informal

markets, and urban villages. Sassen’s idea of “expulsions”—the systemic

pushing out of the poor from urban space—resonates with how Indian cities segregate and invisibilise low-income populations.

Smart Cities, AMRUT, and Urban Policy in India

In response to the challenges of rapid and chaotic urbanisation, the

Government of India launched the Smart Cities Mission in 2015. This

initiative aimed to develop 100 cities as digitally enabled, efficient, and

citizen-friendly urban centres using ICT (Information and Communication

Technology). It focused on area-based development, smart governance,

sustainable infrastructure, and digital surveillance. While ambitious in scope,

critics argue that smart city projects have largely served real estate interests,

created “enclaves of development”, and excluded informal workers and slum

populations.

The AMRUT (Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation)

programme was introduced alongside Smart Cities to improve basic urban

infrastructure—such as water supply, sanitation, sewage, non-motorised

transport, and green spaces—in smaller cities. AMRUT aimed for a more

inclusive development model, but its success has been constrained by weak

urban local bodies, lack of funding, and limited citizen participation.

Overall, Indian urban policy has often been technocratic and top-down, with a

focus on aesthetics, security, and investment attractiveness rather than equity or

inclusion. Urban governance remains fragmented between multiple agencies

with overlapping responsibilities. The absence of strong elected municipal

leadership and participatory planning has weakened the ability to respond to

local needs—particularly of the urban poor, migrants, and marginalised

groups.

Informal Economy, Migration, and the Urban Poor

The urban informal economy forms the backbone of Indian cities. Street

vendors, rickshaw pullers, domestic workers, construction labourers, and gig

workers ensure that cities run efficiently, yet they remain excluded from social

security, housing, healthcare, and legal recognition. Informality is not just an

economic condition but a political status—marked by precarity, invisibility,

and systemic neglect.

Urbanisation in India is also closely linked to migration, particularly

rural-to-urban migration. People migrate in search of better jobs, education, or

escaping caste oppression, agrarian crisis, or climate disasters. However, most

migrants find themselves absorbed into the informal sector, with limited

upward mobility. They face discrimination in housing, policing, and access to

identity documents. The COVID-19 lockdown of 2020 exposed the brutal

exclusion of migrants—millions walked hundreds of kilometres back to their

villages, highlighting the absence of urban social protection and planning for

the poor

Gender, Caste, and Exclusion in Urban Space

Urbanisation is not a neutral or equal process—it is shaped by power, privilege,

and structural inequalities. Women face multiple barriers in accessing safe,

inclusive, and enabling urban environments. Lack of public toilets, inadequate

lighting, and gender-blind transport systems restrict their mobility.

Employment opportunities in cities are often gendered and poorly paid, while

patriarchal norms continue to regulate women’s freedom and visibility.

Caste also remains a powerful axis of urban exclusion. Dalits and Muslims are

often confined to segregated colonies, denied housing in upper-caste localities,

and subjected to everyday discrimination. Urban planning rarely considers

these structural oppressions, and gentrification often displaces vulnerable

communities in the name of beautification or infrastructure development.

In this context, urban space becomes a site of both violence and struggle. From

anti-CAA protests at Shaheen Bagh to housing rights movements in Mumbai,

cities also offer platforms for collective resistance and new solidarities

Environmental Crisis, Sustainability, and the Future of Urbanisation

Rapid urbanisation has led to severe ecological degradation, with air pollution,

groundwater depletion, waste mismanagement, and the loss of green cover

becoming critical challenges. Cities like Delhi, Kanpur, and Varanasi routinely

feature among the world’s most polluted. Unplanned construction,

concretisation, and shrinking wetlands have made Indian cities highly

vulnerable to floods, heatwaves, and water scarcity.

Sustainable urbanisation requires a rethinking of priorities—from car-centric

models to public transport, from vertical real estate to affordable housing, and

from techno-fixes to eco-sensitive planning. Climate-resilient urban planning

must integrate the voices of the urban poor, street vendors, and slum residents

who are often the worst affected yet least responsible for environmental

damage.

Conclusion

Urbanisation in India is at a critical juncture. On one hand, cities represent opportunity, aspiration, innovation, and connectivity. On the other, they reflect inequality, exclusion, surveillance, and unsustainability. Sociologists remind us that cities are not just physical entities but spaces of meaning, conflict, and negotiation. Reclaiming urbanisation as a just and democratic process requires rethinking urban planning beyond infrastructure and investment. It calls for empowering local governance, recognising informal contributions, protecting rights to housing and mobility, and ensuring inclusion across caste, class, and gender. Cities must be seen as shared commons, not commodities. As David Harvey insists, the Right to the City is not only about access but about the power to shape the city’s future—one that is equitable, participatory, and sustainable

References

- Castells, Manuel (1977). The Urban Question: A Marxist Approach to Urban Sociology. London: Edward Arnold

- Harvey, David (2008). The Right to the City. New Left Review, 53, Sept–Oct

- Sassen, Saskia (2001). The GPrinceton University Press

- Wirth, Louis (1938). Urbanism as a Way of Life. American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 44(1).

- Simmel, Georg (1903). The Metropolis and Mental Life.

- India Census (2011). Urban Population Data. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner.

- Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (2015–2023). Smart Cities Mission Guidelines and AMRUT Progress Reports. Government of India.

- Dupont, Véronique (2007). Conflicting Stakes and Governance in the Peripheries of Large Indian Metropolises – An Introduction. Cities, 24(2).

- Baviskar, Amita (2003). Between Violence and Desire: Space, Power, and Identity in the Making of Metropolitan Delhi. International Social Science Journal.

|

|

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|